The forecast predicted perfect working weather: a high of 70 degrees, partly cloudy, a slight breeze, one of those rare days in late Fall when the warmth from a Summer gone by resurfaces and lingers at the doorway one more time. Smoke from the neighbor’s wood furnace drifted in the air and mixed with spent leaves and overripe apple drops. It was Election Day. And for me, like every first Tuesday following a Monday in November for the past seven seasons, it was also Garlic Planting Day.

Garlic is unique: a crop sown in the Fall of the previous season, October or early November for farmers here in New England. I loaded a wheelbarrow with buckets of seed garlic, a metal rake, and a stirrup hoe. The tools bounced over the uneven ground. The garden itself was a blend of what had been and what was to come: carrots to be packed in the root cellar for Winter, kale like miniature palm trees, jumbles of brown tomato vines with orange fruit scattered at their heels: the aftermath of a season-long party.

Election Day garlic became a ritual for me well before I learned that the timing of American elections is tied to our country’s agrarian past. We chose to vote in November because it didn’t interfere with harvesting but is before Winter. We vote on a Tuesday because Sundays were for church, Mondays for traveling to polling locations, and Wednesdays were market day. However, it wasn’t the past that prompted Election Day garlic; it was the future. Seeds, like votes, embody possibility. Both are invitations to tend, select, and improve something over time. Both work in cycles.

Someone called my name. “Liz Jo!” It was Emily, one of my coworkers on the farm, coming toward me down the walking row, her hands outstretched like a gymnast on a balance beam. “It’s Garlic Planting Day, right?”

“Yes!” I replied. “You’re just in time.”

We sat on overturned milk crates, buckets of garlic between us, and broke open the bulbs to reveal creamy white cloves inside clay-colored skins. Garlic reproduces vegetatively, so each clove inside the bulb is the equivalent of a seed. We needed 1,680 of them to fill two beds 140 feet in length. The best bulbs from last year’s crop are used as the seeds. I had sorted the seed the previous day, holding each bulb from last year’s crop for a moment, running my fingers across the contours of its papery wrappers. It was a blend of science and intuition. When I had a seed bulb, I knew.

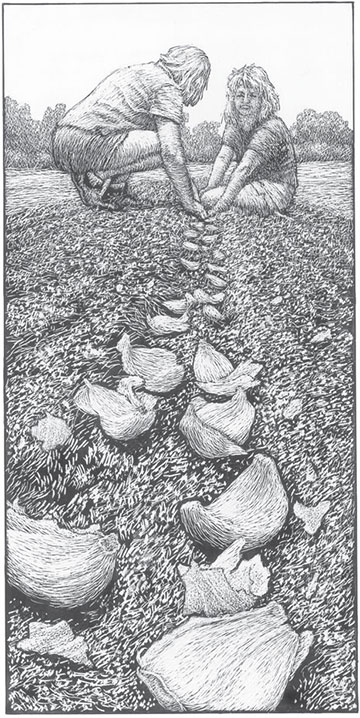

With all the cloves separated, Emily and I knelt on opposite sides of the bed, a bucket of seed each by our side. The sun peeked through the clouds. I pulled my sun hat lower over my brow and gave a short lesson on garlic planting: make a hole, drop in the seed pointy side up, cover with soil, repeat.

“Each seed is a vote,” I said. “Make ’em count!”

I grabbed a handful of bulbs and tucked as many as I could into the ground in one pass, concentrating on speed and ignoring the lower back pain that seems to get a bit more pronounced each season. I settled into a rhythm, working from muscle memory, until Emily’s voice interrupted my focus.

“My first vote is for my kids.”

My hand paused where it had been covering up the cloves. I sat back on my heels and looked at Emily.

“I’m voting for their futures and their dreams,” she said, tucking a seed into the ground with the same tenderness I imagine she uses while tucking her kids into bed at night. She selected another seed from the white bucket and held it up. “And this one, this one’s for refugees.” Prior to fostering her two children, Emily and her partner regularly invited asylum seekers into their home until judges ruled whether they qualified to stay in the United States. Their generosity was something that I marveled at.

Emily put another clove into the earth. “And with this seed I vote for education for everyone across the globe, especially women and girls.” She reached into the bucket, pulled another out, and stuck it in the ground. “This one, for civil discourse.” And another. “And this one, for tolerance.”

I felt the sun warming my forearms. I had said each seed was a vote, but I’d meant it metaphorically. The power of Emily’s spoken votes transfixed me.

I thought of the planning and visioning I did during Winter months. I never imagined pests and disease, a field ridden with weeds, flooded walking rows—much as those were real possibilities. The skies were gray, the air froze in my lungs, the land was drawn inward, and me with it, but still I dreamt of healthy plants with enough harvest to give away, the pinks and yellows of flower blossoms, the hum of bees. And those visions fortified me; it’s when I needed them most. We know that plans without actions are empty, that the arc of justice only bends if we bend it, but perhaps, sometimes, we forget the power of a vision. It is something we can gather around, invite others to join and contribute to.

Emily smiled at me and waited. It was my turn.

“Well, it’s kinda obvious, but I vote for this field. It’s beautiful, resilient, abundant. We care for the land, the land cares for us.”

“To the field!” Emily raised her clove into the air, toasting.

“To the field!” I echoed.

“I will vote for all fields—and gardens, too,” she said, tucking a seed into the ground. “All over the planet.”

Together we moved down the row, planting and voting, our voices starting to blend together. For delicious, healthy food—for everyone. For a balance of economy with ecology. We called out our votes with increased confidence and vigor. For everyone to have a home. Echoes of “Mm-hmm” and “I’m voting for that, too!” followed this declaration or that one. For the animals we share the planet with. Seed after seed infused with our hopes. Sixteen hundred of them. At times our hopes melded into our gratitude for what already was:

For family and friends.

Microbes and music.

Compost.

Sun and rains.

Poetry and kindness.

Laughter.

At the end of the rows, we rose from our knees to spread straw bales over the beds to help protect the seeds during Winter. Finished, we stood back and admired the golden blanket.

“Let’s hope they all come up,” I said.

“They will,” she said. We stood there silently for a bit.

“Now we wait,” I said, finally moving to put the tools back into the wheelbarrow.

“Now we vote!” Emily replied.

As we went to do so, I thought of all those cloves we were leaving behind underground and how, after months in the cold and dark, they would press through the soil and stretch toward the sun.