It started with the death of my daughter’s horse. The cost of hiring someone to come with a truck to load and cart off its thousand-pound body was daunting, so I agreed to inter Kristina’s beloved Arabian pony near the root cellar, a good distance from the house. The coyotes here in rural Washington had been active at night that Spring, so to prevent more carnage, the burial needed to take place the next day. After my desperate phone plea, the county gravedigger, who was not in the habit of digging graves for animals, arrived with his backhoe the next morning, dug a large hole, and as gently as a surgeon with a scalpel, picked up the pony’s stiff corpse and gently placed it in the pit.

After the funeral, I promised Kristina that we would plant a fruit tree above the grave. But which type? We already had too many pear trees; I had been overwhelmed by sheer numbers the previous bumper harvest when they all seemed to ripen at once. I did not want another cherry. Each year dozens of crows moved in from the woods across the street at the first reddening of fruit on our mature Rainiers, and we had to be satisfied with the pickings from the lower branches. Why feed crows?

We agreed on a plum. But what variety? We already had a Mirabelle, a Shiro, and two prolific Italian prunes. We wanted something different. We thumbed through the nursery catalog.

“How about an old-fashioned Green Gage?” I said.

Kristina readily agreed. I think the similarity of the name to Green Gables, the setting of one of her favorite books, convinced her. The catalog described it as yellow-green, juicy with a sweet honey flavor, self-fertile, and adaptable to a variety of climates. The trees were small with low branches and a rounded habit. Perfect! When the bare-root tree arrived by delivery truck that January, we planted it in the loose soil over the pony’s grave. It was a harsh Winter, but the plum survived and grew.

Six Springs later, Kristina had left the nest and was enjoying college life. But the plum had not borne fruit. Perhaps the site was too cold, the soil too rich, or I had overpruned it. Then, in Spring of the seventh year, the small tree had more blossoms than usual. And so did my cherries. The crows invaded them right on schedule in late June, waking me at the crack of dawn with raucous cawing as they descended en masse. I looked out my bedroom window to see the tree laced with black feathers as they enthusiastically commenced their gluttonous orgy of sweet cherries. I shouted at them to stop thieving, but they ignored me.

Our orchard dynamics changed, though, when the Green Gage bore fruit that July. Oddly, the small green plums didn’t look like plums at all. I picked one and bit into it. Though still unripe, its texture was grainier than that of a plum. The shape was wrong, too. When the mystery fruit began to turn yellow, what I tasted was a bland, though juicy pear. Not a Green Gage at all. The nursery must have mixed up the bare-root stock, and I had been sent some type of Asian pear. I had never seen such a small variety of pear, the size of a large cherry—difficult to bite into and flavorless to boot. I didn’t know what to do with them, so I left the fruit on the tree and walked away.

The ravens discovered them shortly after. I could see them from my porch, a pair of these large birds, probably mates. They camped out in a fir on the edge of the property and swooped in to harvest. The fruit was the perfect size to carry in their beaks, and the branches were strong enough to support their weight. Over the course of a couple weeks, I watched them pick the tree clean. I think they took a good survey of the property—plenty of open space, fruit trees for food, firs for cover, a large pond, and that gold mine of a pear tree. They settled into the upper branches of one of the firs near the garden and stayed.

That Fall and Winter, I marveled as the shiny black ravens soared over the field, their wingspans at least four feet. I got used to their guttural calls. Often one perched in a tree on the other side of the pond or on a tall fir next to the driveway and called to its mate in their home tree. Sometimes the call was a series of clicks, and other times it was more like a hoarse croak. I started calling to them when walking outside to the garden or after arriving home and stepping out of my car. They learned to recognize my red Ford coming down the driveway and regularly greeted me with loud croaks as I got out.

Home from college for Winter break, Kristina was amused that the memorial Green Gage was really a tasteless pear and teased me about my talking to ravens. I reminded her how she used to con-verse with her horse, and she hugged me and said she understood.

That Spring, the raven pair was often in the fir by the garden. I knew that crows and ravens mated for life. I assumed they were nesting. In May, the cherries still green on the trees, the crows started gathering in the woods across the road, sending a scout from time to time to check on the fruits’ progress.

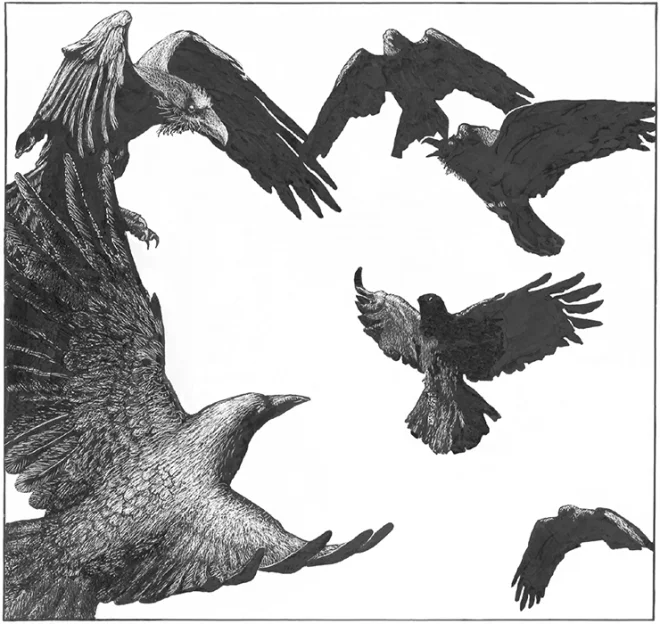

It was then that the Corvid War began. I don’t know who started it. I have read that crows are more aggressive and more likely to attack, primarily to protect territory or nesting sites because ravens have been known to eat crow eggs or chicks. Though smaller in size, a mob of crows can nearly always chase away ravens, who do not form groups and are usually found in pairs. I assumed they were battling over resources, as humans so often do.

That day I felt as though I were living below an aerial battle zone: a murder of crows bombarded the ravens’ fir tree with piercing squawks, and one of the ravens executed breathtaking acrobatic maneuvers to disperse the mob. My heart beat quickly as I watched one of the pair wing to the far edge of the pond, a bevy of crows chasing it. After a day of skirmishes, the noise quieted. A day or two later, I saw one of the ravens return to the nest from the trees across the road with a small black object in its beak. I think it was a crow chick. I took it to mean raven victory. I knew I shouldn’t take sides in a war that didn’t involve me, but I was delighted that the ravens had won.

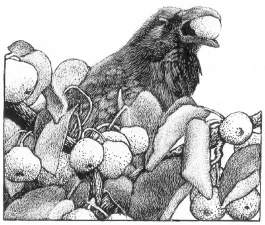

The result? The crows let my cherries alone that year. The ravens, each two to three times weightier than a crow, were too heavy to sit on the supple cherry branches and left the cherries, too, except to glean from the ground below. For the first time, I harvested most of them, leaving the highest to little brown birds I had an affection for.

The July after the war, I was looking forward to watching the ravens harvest from my useless, not-a-plum pear tree. But in this second year of bearing, the tree’s fruits were twice as big as the year before. They were too big for the ravens to carry in their beaks. I left them to ripen on the tree and fall when mature. The ravens could eat them from the ground. In the meantime, I noticed that a central limb on my Mirabelle Plum had been broken. It didn’t take long to figure out that one of the ravens, in search for a beak-sized fruit it could carry back to the nest, had perched on the branch and cracked it. I wasn’t angry. A gardener makes mistakes and learns. The raven did, too. No other plum branch has been broken since then.

That Fall, I enjoyed watching three ravens pecking in the field or hopping down the dirt driveway. One of their chicks had lived, and the pair were giving it survival lessons. The next Spring, the gang of crows attacked again. Corvids have long memories. It was likely the crows had come back to battle for the cherries. I was afraid for the raven family, but they fought to protect their territory and were victorious again. I was relieved.

A year later, tragedy struck. I discovered one of the ravens dead on the edge of the lawn. The bird had gotten tangled in a tenacious wild blackberry vine, had probably panicked, and had strangled to death. I think it may have been the juvenile, but I’ll never know for sure. I mourned our loss. The other two ravens were quiet for a week. I was afraid that they might have left the area. But shortly after, they resumed their calls.

The ravens have stayed on as my garden companions. The Green Gage plum that is not a plum at all bears an unidentified variety of pear each Summer. They are still tasteless, and I leave them to the ravens and other creatures that search for food in the field during the night. And I have learned that sometimes what we plant bears different fruit than we intended—but the harvest can be better than we imagined. ❖

Previous

Previous