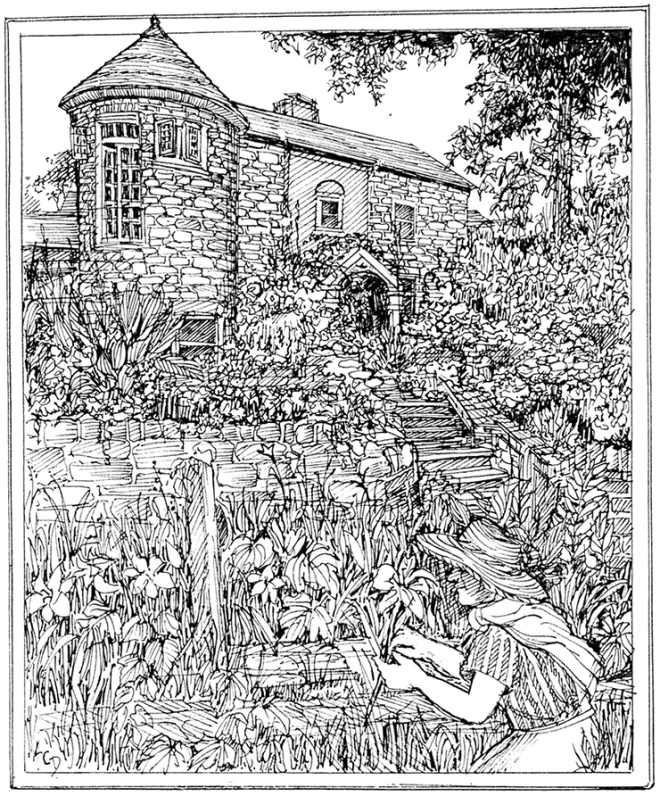

I live on a heavily trafficked corner in the Germantown section of Philadelphia. Cars race up the hill from the main drag and routinely collide with other cars crossing the avenue where my turreted stone house sits on its own little hill.

I created a barrier of stones in front of the corner traffic light—but that was knocked over three times in five years, landing in the garden and destroying it. A few years ago, a big SUV drove right through the middle of my big perennial bed. It ended up near the foot of the front stairs leading up to the house. This situation caused me to write to the Philadelphia Chief Traffic Engineer—then Charlie Denney—so many times that we got on a first-name basis.

But then a great thing happened. A Waldorf School took over the old St. Peter’s Episcopal Church complex, directly across the street from me. Now there are flashing school-crossing lights on the corner—which really slows traffic down. Hallelujah!

My property slopes downward from the house and is held back by 4-foot stone retaining walls. At the foot of the walls were, for many years, plain grassy strips that bordered both sides of the slate sidewalk along the 100-foot length of our property. I decided to replace all the grass with garden. That way I could stop having to mow, take advantage of sunny areas out of reach of two huge shade trees, and have the fun of reshaping a whole new section of my very visible front yard. I began timidly and became bolder season by season.

Street gardening exposes the gardener to all of the passersby—on feet, bikes, scooters, skateboards, skates, wheelchairs, and motorized vehicles of every type. The results are often interesting. For example, some teenage boys started walking by my house, and one looked me in the eye and screamed, “Bitch.” This happened periodically for several months. It was always very unsettling.

I told my son Mike that I had consulted one of my neighbors for advice. I don’t know this man very well, and I was unprepared for his response that I should call on Jesus for help. Without missing a beat, Mike said, “Mom, you should have told the man you do call on Jesus. Every time you see the kids coming, you say, ‘Christ!’”

I developed my garden to mature in midsummer because of the Philadelphia City Gardens Contest sponsored by the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. In eight years of gardening, I entered five times and won several third-place prizes in the large flower garden category and one honorable mention. (I suspect that my garden was never finished enough to get a higher prize: one year a judge mentioned that some areas were a little “unkempt.”) I liked being in this competition because it gave a focus to my efforts and heightened my motivation. The judges always came between mid- and late July, and I made sure to have a lot blooming. I’ve retired from this contest, but still put in the same fussy care as when I was getting ready for the judges. I suppose I consider the regular passersby to be the judges now. Really, this has always been the case.

Part of my work this week is to weed and edge the vegetable beds. I have peppers, eggplants, pole beans, radishes, and cucumbers, all producing. Next to them are perennial flowerbeds, arranged for variation in height, width, leaf texture and tone, plus, of course, color. Closest to the street are bee balm, several grasses, false sunflowers, fennel, echinacea, tall phlox, cardoon, Oriental lilies, yarrow, hollyhocks, pink evening primrose, a bushy Japanese willow, cannas, two fruit trees, a grapevine growing on a pergola my sons built for Mother’s Day several years ago, a butterfly bush, and more. Against the garden wall there is a border of daylilies and indigo salvia. On the corner itself, which is in full sun all day, I have a bed of zinnias with rudbeckias behind.

Bastille Day. The French holiday has nothing to do with my garden, except that the date always says to me “freedom.” Freedom (in a different sense) is how I approach gardening. I establish shapes and volumes with found objects—primarily metal things, rocks, and wood stumps. I try to create conversations between the organic and the inorganic inhabitants. Ultimately, I am not so much growing plants as creating spaces for them. I give myself more freedom in this activity than in any other sphere of my life—I don’t know why that is. Perhaps it has something to do with how a garden is never predictable. Even if you were to grow exactly the same plants every season, you would not achieve exactly the same effect. Weather conditions change year to year, the shrubs don’t stay small, and your eye discovers new possibilities of form and color. Nature gives me my freedom.

Today I got six bucketfuls of free compost from a local recycling center (I do this all season), had a quick lunch, and then tackled the overgrown daylily beds along the front wall.

One of the passersby took a half-hour of my time, but the encounter was too interesting to cut short. The man was in a wheelchair, but that’s a recent development: I’ve seen him walking the streets of my neighborhood for many years. He is eccentric. He lives in Fairmount Park, under one of the bridges near my house. He has erected a lean-to there and seems to sleep outside all year long. I have avoided him for the most part, taking him to be weird and possibly dangerous. He got mad at my dogs when I walked by him one time, yelling and shaking his stick, and that scared me.

But as we both have aged, it has become clear to me that he is not dangerous. Seeing him approach today in his wheelchair, which he handwheels laboriously, I spoke to him and asked what had happened to put him in a wheelchair. He told me his feet had gotten frostbite, and he’d lost a few toes. He can walk—sometimes he pushes the wheelchair in front of him-self—but this time he was riding. He got so enthusiastic about our conversation that he announced he would talk to me every time he sees me from now on. I hope I have not opened Pandora’s Box.

Some people think a garden is only a frill, an extra tacked on to the real business of life; merely a decoration to the roadway that takes us where we really need to go. Not me. I think the garden is the place to go: with its color, its form, its scents and accents, its rhythms, its health. The garden is what makes the roadway—and life—both beautiful and bearable. The worse off society is, the more we need those plants. And they will not fail to oblige us. ❖

Previous

Previous