A chunk of heaven. This was one gardener’s description of the late Elsa Bakalar’s teaching garden in the Northern Berkshires of Massachusetts. For the 12 students who had come to learn, the title was apt. We ranged in age from 30 to 60. Some of us were professional landscape architects who had found their education in “plant material” sadly lacking; some were beginner gardeners; some were skilled and just thirsting for more. All were thrilled to be there.

Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum had promised that the weekend workshop would provide an in-depth understanding of perennials. It was 1991, and as a novice, I was all-in on that prospect. The two-hour journey for me seemed trivial compared to that of others who had traveled from Maine and Rhode Island. But any journey was worthwhile for hands-on learning from a woman the Arnold Arboretum described as “the doyenne of perennial gardeners.”

In the years to come, Elsa Bakalar became not only my mentor, but my friend. I took my “Gardening Fools” pal Marge to meet her when Bakalar’s long-awaited book, A Garden of One’s Own, was published in 1994. Another year, I introduced my mother to Elsa when she came to visit from England. Sadly, Elsa Bakalar died in 2010 at the age of 91. Her dear husband, Mike, had preceded her, and I know she was lost without her companion. (She once told me the story about the time she received a bareroot plant she’d ordered from a mail-order nursery and Mike remarked, “Someone has sent you a stick.” She also said that as they got older, they made a pact not to groan upon standing or sitting.) It seemed that a lot of Elsa’s spark died with Mike.

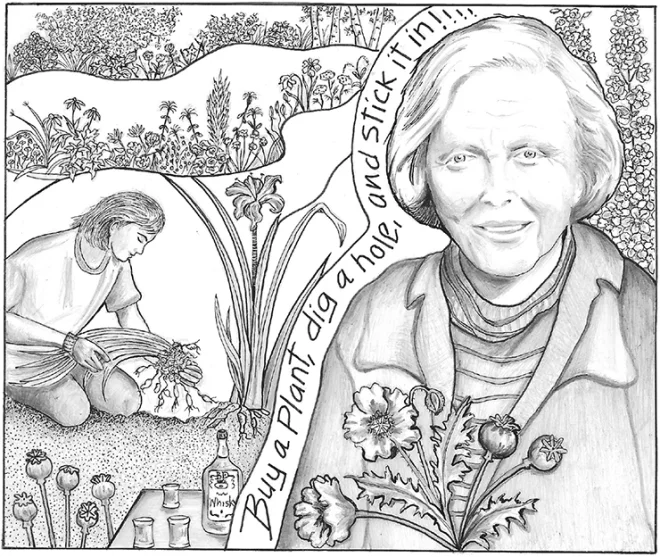

But at that famed perennial workshop back in 1991, Elsa was in her element. With her youthful blond pageboy, boundless energy, and quick dry British wit, she seemed much younger than her 70-odd years. In fact, she joked that she’d had a group of senior citizens come to see the garden—and realized she was older than most of them. “There they were, sitting there being elderly, and they asked, ‘How do you get started?’ I said: ‘Buy a plant, dig a hole, and stick it in!’”

Before this most active of retirements—consulting and working on 15 gardens as well as her own—Bakalar taught English literature in New York City. It was while living there that she and Mike bought a Summer place in the northwestern corner of Massachusetts. It was as basic as a Summer cottage could be. During a photoshoot of the garden for Better Homes and Gardens, the editor called and asked her to describe the style of her house.

“Style?” she replied. “Hmm, let’s see. It’s like a toolshed, with plumbing.”

Visitors had to leave their cars and walk the final stretch, over a small wooden bridge, around a pond, and up to an elevation of 1,800 feet. There, atop a hill and beneath a big dome of sky, the flower garden dazzled like a multi-jeweled offering to the gods.

Delphinium spires of cobalt, sapphire, and snow reached skyward, dancing on the breeze with airy pincushion flowers (Scabiosa caucasica) and the lacy fronds of meadow rue (Thalictrum). A small, luminous Sedum sieboldii tended the soil, while at mid-height floated a wash of palest yellow, the yarrow Moonbeam (Achillea). Scattered throughout were the pastel nodding heads of annual poppies—a mainstay of English gardens but illegal to buy in the U.S. “You simply throw the seeds on the snow,” Bakalar told us. “They come up where they will and cannot be transplanted. But look at them! They’re so delicate and sweet.”

Every flower was beautiful, but the show-off of the day? Crambe cordifolia, a huge fountain of frothy white lace that erupted a full six feet from its cabbage-like soul. It was a bridal veil, only lacking a bride.

The hilltop location of this garden, spectacular as it was, was also a tool for teaching about soil. Since it was depleted of all nutrients by overgrazing and exposure, Bakalar had started out by dredging silt from the bottom of her pond and dragging it up the hill to the site. The lesson? Compost and organic matter first, flowers second: “You want a $10 hole for a $2 plant.”

Bakalar then asked a local farmer to till the soil for her first garden. He turned up a nice neat, rectangle. When she explained she wanted to “grow some lovely flowers” and sought curves and flow, he said, “Well, if I’d known you wanted a posy patch…”

She set to carving out the curves she sought by hand. Curves evolved into terraces that embraced small patches of lawn like a hug. The beds were planted with drifts of perennials in groups of threes, fives, and sevens, creating a gorgeous paisley fabric on the earth. A posy patch, indeed!

“I’m not a trained person, but one who has learned by doing,” she told this group of students. From a woman who had lectured at the Williamsburg Garden Symposium and the New York Botanical Garden, this was refreshing.

Resembling a school of awkward fish, we eager students spent the day learning by doing. We followed, en masse, about those curves and terraces, wherever Bakalar moved. We pinched and pruned, dug and planted, listened and learned. She had us dig up daylilies that needed dividing, instructing on the two-garden-forks method of prying them apart. She lectured on the importance of teasing out the roots of a pot-bound plant, of soaking the soil in the hole, letting it drain, filling it with compost, tamping it down with our feet, and watering again. Once she turned the nozzle on so high we scattered, laughing as mud spattered our faces. We welcomed it—the day was in the high 80s. By day’s end we were grimy, sunburned, exhausted… and smiling.

Mark Twain was once said to have re-marked, “If you don’t like the weather in New England, wait a minute.” This truth was in evidence on the second day of the workshop. Yesterday high 80s, today low 50s and bucketing down rain. Emerging from our motel digs, we eager students gamely crossed the little wooden bridge and trekked around the pond and up to the terraces, shrouded in low clouds and pounding rain. Ah, yes, New England.

In just a short while we were all drenched and chilled to the bone. Finally, Elsa called it a day. She brought us all into her house and started out handing out towels and shots of whisky. Then out came the ziplock bags of those illegal but innocent annual poppy seeds to take home. “This is a bit like a drug deal, isn’t it?” she said. “Plying you with whisky, handing out baggies. I’m not sure the Arnold Arboretum would approve.”

We students approved, however. We each went home with daylily divisions we had created, wrapped in damp newspaper, and baggies of seeds to create our own pastel drifts. We trekked back down the hill with our treasures, exhausted but blessed.

Hands-on learning from the doyenne of perennial gardening? It wasn’t work. It was a chunk of heaven. ❖

Previous

Previous