Are you a morning person or an evening person? I am very much a morning person. I seldom wake after 5 a.m., but by 7 p.m. it’s dull to be around me! My husband was an evening person. He tended to be withdrawn at breakfast, whereas I never wanted to do much after the sun went down. Our best times together were during the middle of the day: we always had lunch together.

Early mornings in Summer I would have breakfast on the porch, listen to the birds, and feast my eyes on the Heavenly Blue morning glory. It was always planted exactly where I could best see it from my chair, and it always opened its trumpet flowers in time for my breakfast. The moonflower, though, also next to the porch, opened in time for me to yawn, remark on its heavenly scent—and start to think about bed.

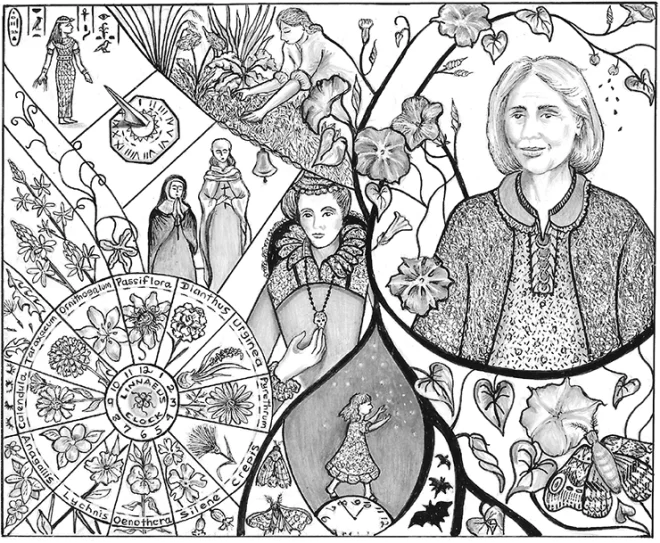

My husband would often remain on the porch, watching the bats come out and saturating himself into the soft dusk. I would plant other evening plants for him—mostly with white, scented flowers that attracted fluttering moths seen through the screening. There would be fireflies, too, and when she visited, my little granddaughter chased them, laughing and dancing fairy-like over the darkening lawn.

All living things, including plants, animals, and ourselves, respond to a circadian rhythm. The term “circadian” comes from the Latin circa, “about,” and di, “day,” and describes how living things respond to the movement of the earth, sometimes (to us) with almost uncanny accuracy, even if their environment is artificially changed. When hamsters were taken to Antarctica and put on a turntable to counteract the normal rotation of their lives, they continued to sleep and wake at their usual times. Unless they have been genetically modified, fruit flies, or Drosophila (the name means “lover of dawn”), wake in the morning, have a rest at midday, and sleep at night, regardless of laboratory conditions. Apparently even bananas always make their new cells just after dawn.

Carl Linnaeus, famous for classifying living things—dividing them into families and species—wrote Horologium Florae in 1751, describing his idea for a “Floral Clock.” This would tell time according to the time of day different flowers opened or closed. He wrote that he could “plant a clock that would put the watchmakers out of business.”

He never, as far as we know, made this clock, although he did make a list of the different flowers that he claimed could be relied upon to open at certain times. “Hawksbeard (crepis),” he wrote, “opens between 6:00 and 6:30 a.m. and closes at 6:30 to 7:00 p.m. Indoors, in water it opens at 6:30.” His clock included hawksbeard, dandelion, passionflower, marigolds, pinks, star of Bethlehem, and evening primrose. His list, however, did not specify the season these flowers bloom, the length of day and latitude where they grow, or the weather. He did not, as I say, make such a clock—but others have tried to do so with varying success.

It’s a lovely concept and even inspired the mid-20th-century French composer, Jean Françaix, to write L’horloge de Fleur (“Flower Clock”) for oboe and orchestra. It depicts flowers opening between 3:00 and 11:00 p.m., including moonflower and night-flowering catchfly. Just think if we used such clocks: I can picture secretaries peering out of their office windows to see if the flowers are bright enough for a lunch break—and sending someone down to see if they were properly closed for the workday to end!

In spite of Linnaeus’s plans, the watchmakers, far from being out of business, have prevailed. They, not our circadian rhythms, dominate our lives. Not always to our benefit: high-school students notoriously doze through early classes. Travelers ignoring jet lag struggle to keep awake when making important decisions. Clocks rule our lives. Indeed, at the time of writing this, we have just changed our clocks to “Summer” and must wake an hour earlier.

Since prehistory humans have recorded the passing hours in different ways. According to the ancient Egyptians, an instant was the time it takes a hippopotamus to look up and check for danger. From the time of ancient Egypt, sundials were used to track passing time (as long as the sun was out). In the classical world, time was often measured by a dial turned by dripping water. On the whole, though, most people simply worked according to the sun and didn’t need accurate clocks. That changed with the early Christian monasteries. Monks and nuns had to pray at specified regular intervals regardless of the weather and the season. They could use water clocks and candles with the hours marked off. But someone had to watch these and ring the bells when the right number of hours had passed. The bell was at the top of a tower, and weighted ropes rang it when pulled. This bell was called a clocca, which gives us the word “clock.”

By Linnaeus’s time, watches were commonplace. One of the earliest watches belonged to poor Mary, Queen of Scots, in the 16th century. It was heavily jeweled and in the shape of a skull, designed to hang from her neck. It bore what turned out to be a prophetic inscription: “The impartial foot of pale Death visits the cottages of the poor and the palaces of kings.”

We gardeners know time in the best way of all—the way of forgetting it. We’ve all spent hours pottering and then suddenly checked the time and wondered where it went. But we are also acutely aware of the slightest changes in our gardens. A century before Linnaeus, the poet Andrew Marvell wrote:

How well the skillful gard’ner drew

Of flowers and herbs this dial new;

Where from above the milder sun

Does through a fragrant zodiac run;

And, as it works, th’ industrious bee Computes its time as well as we.

How could such sweet and wholesome hours Be reckoned but with herbs and flowers!

But Marvell is like other gardeners, he’s not really watching the time. His mind, he writes, is:

Annihilating all that’s made To a green thought in a green shade.

And I, too, lingering over my breakfast on the dawn porch, can let a long time pass before I get myself together and start my day. It’s just impossible to stop bathing my spirit in the utter, extraordinary blueness of the morning glory. Whatever I meant to do is forgotten.

And, for a while, time stops. ❖

Previous

Previous