Read by Matilda Longbottom

She was the most ornery, irritating dog that ever was. She looked like a cross that no breeder ever could have achieved, between a favorite toy . . . and a jackal. She had very large ears, and someone, before we got her, had named her “Rabbit.” She didn’t look like a rabbit, but the name stuck. If there was a foul-smelling carcass anywhere within miles, she would find it, roll in it, and come home with that slightly ashamed, slightly triumphant look of a woman returning from the beauty parlor with a new hairstyle. She would then be bathed or banished, according to the weather. If we called her to be bathed, she would lie down and slither on her stomach as if her legs were paralyzed. When released, clean and fluffy as a Christmas toy, she would immediately head for the smell again. Usually, we gave up and let her stay outside for a few days until it wore away.

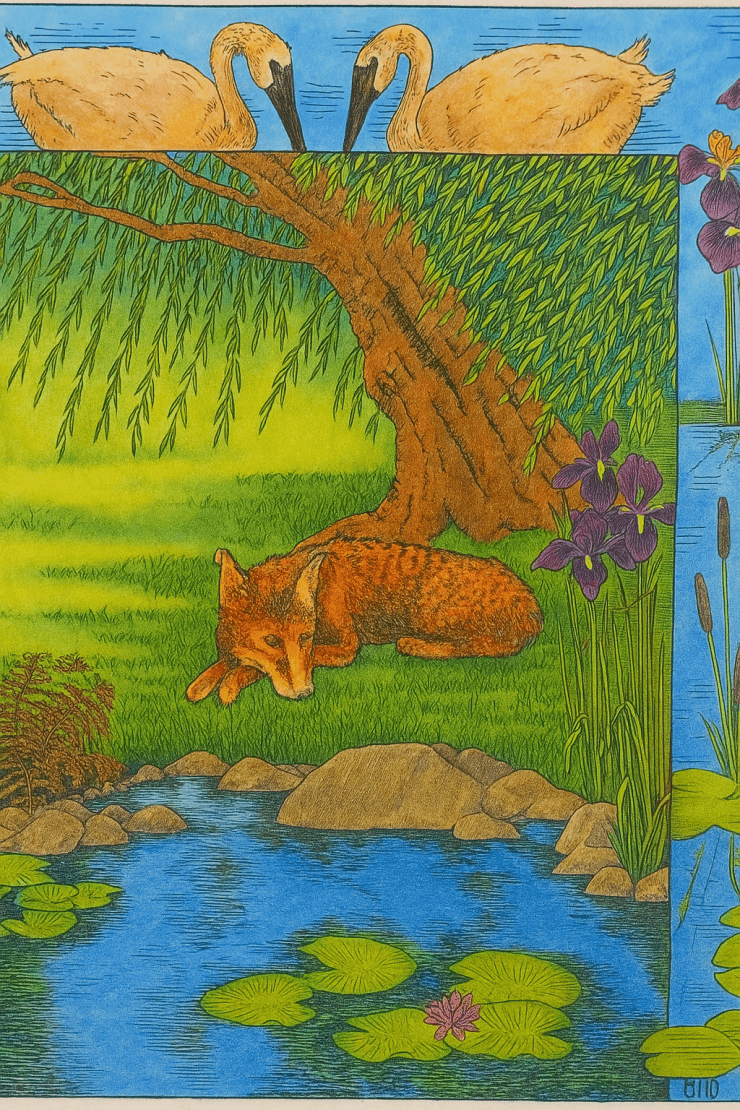

Rabbit used to lie under the weeping willow by the pond and wait for frogs or garter snakes, which she caught with phenomenal skill. Then she would leave them until they were properly ripe (unless we could find the carcass in time and throw it into the bramble thicket). They smelled the best of all and usually she had to camp out for a week after one of those—not that she minded. She really preferred her doghouse, and we would have left her outside all the time except that she drove us crazy barking on moonlit nights. When we did keep her in, she often messed in the kitchen. We suspected she did it on purpose, because she certainly didn1t lack intelligence. I knew why she had been taken to the dog pound, where we got her, and she knew I would never take her back there.

The weeping willow where she caught frogs had fronds reaching to the water, forming a thick green tent beside the pond. The children played forts and houses under it when they were teenagers. Willows have always lent themselves to secret occupations:

“Down in the Willow Garden

Where my love and I did meet…”

Because so many lovers used the fronds as friendly hiding places, willows came to be associated with love itself, especially jilted love:

“In love the sad forsake wight

The willow garland weareth,” as Shakespeare said.

Jilted love and illicit love sometimes lead to awkward situations, and awkward situations, as we know, sometimes lead to crime. That same willow garden was where:

“I had a bottle of burgundy wine

Which my true love did not know

And there I poisoned that dear little girl

Down under the bank below …”

Unless she was quick enough to save herself:

“Then he turned his back around

And faced yon willow tree,

She caught him around the middle so small

And throwed him into the sea.”

As well as stalking frogs, Rabbit hid under the willow tree to eat eggs. She stole the hens’ eggs with amazing cunning and intelligence. It took us weeks to understand why the hens had “stopped laying,” as she grew fatter and glossier each day. By the time we caught her, red-pawed, she had learned to balance an egg, bite its top neatly off, and lick out the inside without spilling. That finally explained the puzzling, almost intact eggshells we had found under the tree.

Willows are of the salix family. Their flexible branches have been used from ancient times for basket weaving and even for buckets because they expand when wet. In Ireland, baskets for peat and other uses were woven at home from a grove of willows by the house, called a “salley garden” (from the name salix). Here it was that the poet Yeats’ lover “passed the salley gardens with little snow white feet….”

Weeping willow trees were named Salix Babylonica because they were thought to have originated from beside the rivers of Babylon where the exiled Jews “wept when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof…” (Psalm 137). It was thought that the weight of the hanging harps had pulled down the willow branches, which remained pendant ever since. Actually, the tree probably originated in China. It was introduced to England in the eighteenth century along with other Chinoiserie, including the first willow pattern plates made then which, not surprisingly, show lovers eloping over a bridge under a willow tree chased by an irate father.

The lovers are also shown as two doves in the sky, which implies that all did not go well with them. If they died, a willow tree was appropriate, too, for from ancient times it was associated with death. A willow garland was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. The willow, unlike the cypress, also a tree of death, will regenerate itself if cut, so it was a more optimistic symbol. It also had healing powers its bark contains salicin, which is an ingredient of aspirin. However, the name “aspirin” is coined from acetylsalicylic acid and spirea, a meadow sweet that also contains salicin. The ancients thought the trees grew in wet places to provide a cure for gout and rheumatism, the theory being that those ailments were associated with dampness and that God provided a convenient cure for every ill. Weeping willows were used a great deal by Victorians in the nineteenth century, both as graveyard trees and carved on tombstones. Andrew Downing recommended planting willows, since their light and elegant foliage flowed like the disheveled hair and graceful drapery of a sculptured mourner over a sepulchral urn. He added that the tree “conveys those soothing, though softly melancholy reflections which have made one of our poets exclaim, ‘There is a pleasure even in grief.'”

One morning we couldn’t find Rabbit. We searched for her and finally found her lying in the doghouse. No guilty look, no tail wagging— she didn’t even smell. She just lay there. I took her to the vet and, after examining her, he gently said that there was nothing he could do. She was dying. We could have put her down or brought her home. She was not in pain, so I decided to bring her home. We put her back where she had chosen to be, in the doghouse. She lay there for a week. Each morning, we expected to find her dead. Sometimes she would wag her tail a little, sometimes her ears would prick when we whispered her name. She would not look at food or water. We thought of moving her or taking her back to the vet, but there was something about the way she looked at us that made us leave her there.

Then we had snow. We covered the whole doghouse with thick tarpaulins to keep the cold out. She wagged her tail a bit when we tucked her in. We even had a little hope that night that she might recover. The next morning, she looked a little better. It was snowing heavily.

Then, at lunchtime, she was gone. We didn’t believe it: we felt sure she wasn’t strong enough to walk. We searched for her all day, calling her, looking for footprints in the fast-falling snow, poking into briar patches hung with icicles, tangling our coats and hair in the thick brush. We didn’t find her. She had not intended that we should.

It was not until the Spring, after the snow had melted, that we found her body under the willow tree. Of course, we buried her there. The new leaves of the willow formed a bright green tent around us as we dug. The season of sleep was over, and the trees knew exactly what to do, just as in Autumn they would know to shed their leaves. Just as she, whom we had laughed at, raved at, and loved, had known exactly, when the time came, what to do. ❖

Previous

Previous

That’s a very touching story. It made me cry a little.

Thank you, Diana For another wonderful story.