Read by Michael Flamel

Greetings from the Autumn of 1621! That’s right—your faithful gardening reporter has hitched a ride in a horse-drawn wormhole to bring you a firsthand report from the very first Thanksgiving celebration held right here in Plymouth Colony.

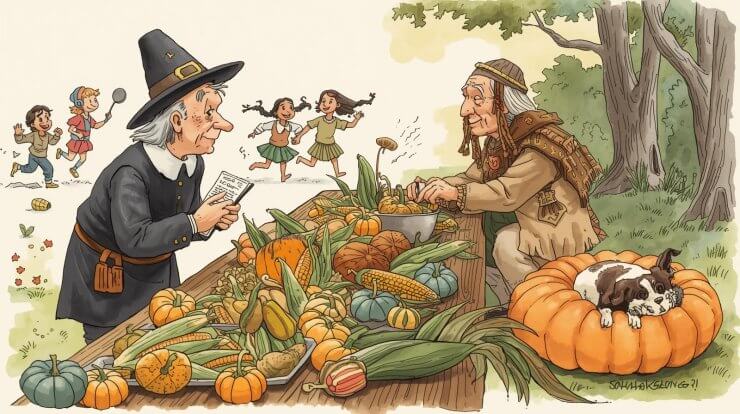

After several sun-drenched days of harvesting corn, squash, and pumpkins—not to mention hunting fowl and fishing for eels—the English settlers and the local Wampanoag people came together for a three-day feast that was equal parts diplomacy, gratitude, and good old-fashioned merriment.

Setting the Table

Roughly 90 Wampanoag men, led by Chief Massasoit, joined 50-some surviving colonists—only about half of the original Mayflower passengers remained after a brutal first Winter. The gathering wasn’t marked by a precise calendar date but took place sometime between late September and mid-November. The celebration was sparked by a successful growing season, thanks in no small part to the Wampanoag, who had shared their knowledge of the local land and crops.

My gardening heart swelled as I saw raised mounds of corn interplanted with beans and squash—a brilliant growing method known as the Three Sisters, practiced for centuries by Indigenous peoples. The squash leaves shade the ground, the beans fix nitrogen, and the corn gives everyone a reason to grow tall. Honestly, I’m thinking of converting my whole backyard back home to this system.

What Was on the Menu

Let’s clear up one myth: there was no pie, stuffing, or cranberry sauce shaped like a can. But what was on the menu? Oh, dear reader, the bounty was mouthwatering:

- Roasted venison (Massasoit’s hunters brought five deer.)

- Wild turkey and duck (The colonists contributed fowl aplenty.)

- Stewed pumpkin, roasted squash, and boiled corn porridge

- Shellfish, including mussels and clams cooked over hot stones

- Nuts, berries, and dried fruits—especially wild grapes and plums

- Cornbread and hominy, pounded and boiled to hearty perfection

There was likely some celebratory sipping of fermented fruit beverages, too, though I suspect the elderberries did more fermenting than filtering.

Festivities and Commentary

Over the three days, I witnessed foot races, archery contests, and even a laughing competition between two particularly jolly English children and three Wampanoag boys who had mastered the art of mimicking a turkey’s gobble.

“I think the corn is tastier when you dance while planting it,” said a Wampanoag grandmother, who shared that singing and gratitude were part of every step of the growing season. “The plants feel it.”

Edward Winslow, who fancies himself a bit of a gardener among the colonists, commented, “I had no idea what to do with pumpkins before this Summer. Now I can’t imagine a meal without them. They are most agreeable when stewed with a touch of ash and maple sap.”

A 10-year-old English girl named Constance confided, “I do wish we had sugar for sweets, but the Wampanoag made something with pumpkin that tastes like pudding and firewood, and it’s quite good!”

A Dessert Worth Giving Thanks For: Native Pumpkin Stew

In honor of the season, here’s a reconstructed and historically grounded dessert dish—shared with me by a generous Wampanoag woman named Nittôpus, who laughed at my quill pen but kindly gave me the recipe anyway.

Maple-Roasted Pumpkin Pudding

Ingredients:

- 2 cups pumpkin, peeled and cut into chunks

- 1/4 cup maple syrup or honey (Or use molasses for a richer taste.)

- 1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon (optional, if available)

- 1/4 teaspoon ground nutmeg or ginger (if trading allowed access to spices)

- 1/2 cup crushed walnuts or sunflower seeds

- A pinch of salt

- Water or milk (if any livestock are producing)

Instructions:

- Roast the pumpkin chunks over hot coals or in a clay pot near the fire until tender.

- Mash the pumpkin with a wooden spoon.

- Stir in maple syrup or honey, spices (if available), and crushed nuts or seeds.

- Cook slowly in a pot over the fire, stirring until thickened.

- Serve warm in gourd bowls or with flat cornbread.

This dish, though humble, carried warmth and sweetness into a meal otherwise dominated by savory flavors. I watched English settlers nod with delighted surprise as the dessert was passed around—many reaching for seconds.

As the stars blinked over the treetops of Plymouth, I sat near the fire, surrounded by people whose lives could not have been more different—yet who came together over a harvest, a meal, and the hope of a new life.

For gardeners like you and me, this moment in time reminds us that the simple act of planting, growing, and sharing food can build bridges, warm hearts, and shape history.

Until next time—whether that’s 1621 or next season’s planting time—I remain your humble, time-traveling gardening reporter,

Don Nicholas

P.S. If you’re inspired by this tale, I invite you to try planting your own Three Sisters Garden next Spring—and share your harvest with someone new. Who knows what friendships might bloom? ❖

Previous

Previous