I never wanted to learn to prune. I thought of myself as a grower, not a pruner. In fact, I knew exactly what kind of gardener I was: a plantswoman. My borders might originally have been designed with color or theme or impact in mind, but pretty soon they became a hodgepodge of plants I just hadn’t been able to resist, sometimes because they were beautiful or rare and sometimes because they were on the sale table, looking wilted or scorched—or dead. (I never could resist that kind of challenge.) So I stuffed my space with lopsided shrubs, apparently expired bulbs, and—of course—cuttings of things I’d seen in my friends’ gardens.

If anybody visited my crammed-in garden, I could tell them the history of each plant, the challenges it

had faced, and what its presence meant to me. I imagined it was like having a dozen kids: our home life would look chaotic to other people, but to me each beloved child would be unique and valuable, and all would deserve their places, even if they had to stick out their elbows to keep them.

Pruning was not my bag. OK, I’d cut a plant back if it was harming a neighbor (given the way I brought home every horticultural stray, that was a pretty common occurrence), but pruning for aesthetics or performance never entered my mind. Until we got an allotment, that is.

Allotments are uniquely British institutions, pieces of land that can be rented to grow crops to feed your family. Unlike many American community gardens, they aren’t a group activity, and unlike the tiny strips of vineyard that French families guard so jealously, they aren’t handed down through the generations. Anybody can have an allotment, although relatively few people, when it comes right down to it, are capable of running one. A traditional allotment, called a plot, is ten poles in size. That’s around the same area as a doubles tennis court, and it should be kept in good cultivation all year round. Sometimes they aren’t, and the plot becomes overgrown and full of rank weeds.

The allotment plot that my husband, Tony, and I were given had trees—way too many trees! We paced among them, debating.

“We need to keep the apple trees,” I said, gazing at them, not-ing they were as thick around as my waist, while their branches were so entwined they had turned into one huge tree tangle.

“And we’ll get rid of these two rowan trees and that oak,” Tony said confidently. “Surely they’re only here because birds or squirrels dropped the seeds and nobody weeded the saplings out.”

But the two elder trees divided us. “Should we keep them? Neither of us likes elderberry jam,” I said.

“Should we remove them? We do both like elderflower cordial,” he replied.

We compromised. We’d prune them back and see how they did.

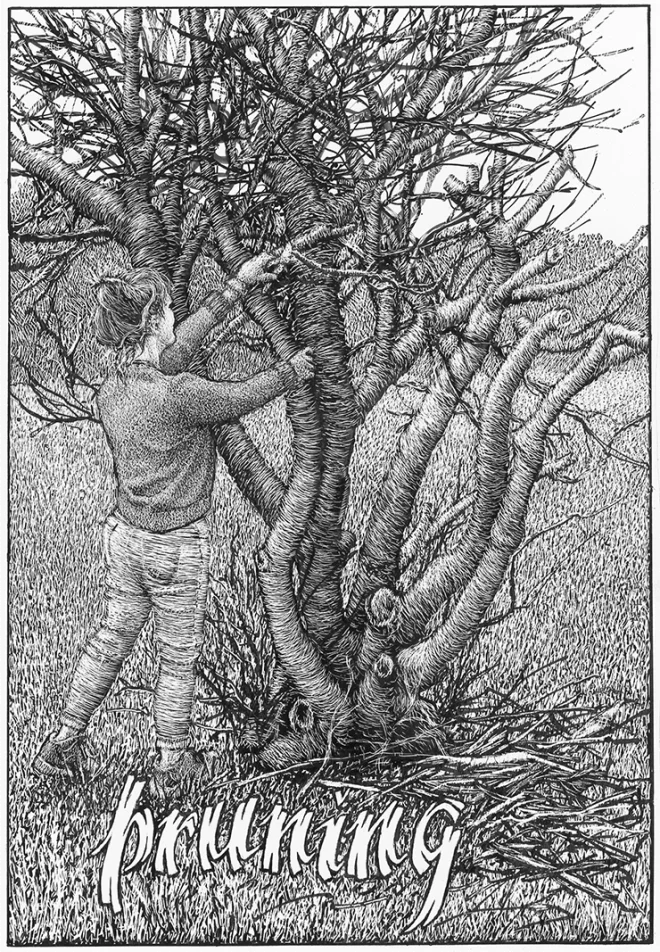

Then Tony fell ill. It wasn’t obvious what was wrong, and he began undergoing a series of tests that were as worrisome as they were inconclusive. That meant that the trees became my business. So one chilly Winter day I headed up to the allotment, borrowed loppers and beloved secateurs in hand, to “get things in order.”

It was hubris. Hacking down the oak and rowans wasn’t difficult, although digging out the roots was going to take months. No, the problem was the apples. I’d read an article or two online about creating an “open heart” with “air circulation for the branches,” which all sounded very nice and quite yogic. But when I actually confronted the snarl of branches rising from elephantine trunks, I felt like the prince outside Sleeping Beauty’s castle, trying to hack through the brambles and rambling roses with a totally inadequate sword.

Of course, each evening when I went home, I told a very different story: “I’m doing great. It takes a lot of work to get trees back into shape, but I’m sure they’ll be fantastic by Summer.”

Neither the trees nor Tony were fantastic by Summer. He had cancer and needed major surgery, and my apple trees put up a thousand water sprouts and were more entangled than ever.

I couldn’t help seeing the metaphor. But while Tony was in the hands of an expert surgeon, the apples had been left to my less-than-competent care.

It was obvious what needed to happen. I signed up for a pruning course.

Over the next few months, my life changed forever. Under the guidance of master pruner, a small group of us learned the different shapes a fruit tree could take.

“Espalier, fan, bush, pyramid, cordon, step-over,” I chanted to myself as I traveled to and from the hospital by bus, taking food to Tony, who refused to eat anything their cafeteria provided, finding it pretty awful stodge when he was used to homegrown fruits and vegetables. ❖

Previous

Previous