Read by Matilda Longbottom

Down in a little stream valley in Virginia, where green comes in 48 shades and fireflies delight the senses on warm Summer evenings, a war has erupted between two otherwise sensible people. There has been no bloodshed at this point, as it is of the passive-aggressive variety so common in marriages of a certain age. But as both parties are actively engaged, and there is a machine with three rotating blades at the center of the fray, it would be unwise to completely rule out the possibility of escalation.

The story begins with a mower.

The couple had never cared much for mowers. She had always landscaped lawns right out of their tiny properties, and he had never been that inclined to push a mower around on a Saturday afternoon even if she hadn’t.

But with the purchase of the ten-acre property that the couple had always dreamed of, a zero-turn mower came into their lives. The owner, who had built the house forty years before and spent the subsequent years clearing a pastoral scene from amongst the brambles and overgrown thickets, kindly included the mower in the sale.

He showed the man how to tinker with it, gave him the original manual, and left him with the cryptic words, “You’re going to need this thing—nature wants it back.”

Indeed. It soon became apparent to both the man and the woman that mowing was a defensive strategy, not a design choice. Nature wanted it back indeed, and nature didn’t work in sweet, bluebell-woods fantasies or rippling wildflower meadows. The land had to be managed, or it would become as choked as the impenetrable woods that surrounded it.

But maintaining long stretches of mixed-weed lawns subtracted four hours from a busy week; and as years passed and the structural integrity of the mower began to fail, another hour or two of tinkering and swearing was added to the weekly event. There was never mowing without jury-rigging. Sometimes there was none of either without Amazon Priming and wallet-gutting.

In the midst of this struggle twixt man and mower, the woman was building a garden. Except it wasn’t so much a garden as it was many gardens, and they suffered from an issue common to properties of size: they were disconnected from each other.

With an unlimited budget, this would of course not have been an issue. Fully landscaped paths would have led visitors from the pergola garden to the sunny serpentine bed through to the woodland garden 300 yards away, and the visitor would have been none the wiser that he had been led. But as it was, vast stretches of open space separated such jewels, and many a visitor was lost halfway to the glories of woodland trilliums by the easier promise of drinks on the deck.

And so it went: the woman searching for a way to connect the gardens, the man swearing over his mower, until the first of three events happened to change the status quo.

It started raining and didn’t stop.

Saturated turf being no friend to wheels or blades, the man found himself having to watch the grass grow higher between mowings; and as his machine continued to break down, he found himself less inclined to care.

The woman, delighted by the subsequent appearance of thousands of violets and claytonia on the scene, followed by a contingent of ornithogalum and clover, approved mightily. She was saddened when the man would finally muster the energy to swear over his machine in the barn and once again bring the landscape into some sort of order.

Then the second of the three events occurred.

The woman went to England.

In her capacity as a guide for a garden touring company, she led a merry band of fellow gardeners through great English gardens in the late Spring. And when she returned, it was not dreams of roses and delphiniums that occupied her thoughts. It was the idea of using the mower as a pathfinder—a way of connecting cultivated spaces through natural, bulb-filled meadows.

Things had been changing in Europe and the UK—even Hyde Park had climbed on board the meadow craze. Though the woman knew that the process could be complicated, she was enchanted by this new paradigm and, moreover, saw it as a solution to their issues.

But would the man agree?

She cajoled him in the early, beautiful mornings over black coffee and perfectly fried eggs, and found him, surprisingly, persuadable. Though he quite justifiably worried about having the equipment to fell the grasses et al. at the end of the season, he had noticed that the bees had already stored an inordinate amount of honey in their boxes—and rightly put it down to the clover and dandelions that had been allowed to bloom for weeks.

The man loved honey.

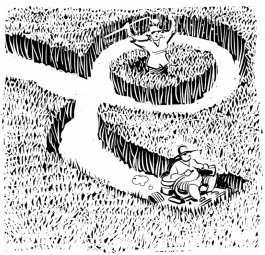

So the woman mowed her paths, trimmed an outline around areas of woods to discourage the rooting tips of multiflora and brambles, and looked forward to the season ahead.

But the third and final event was to change everything. The old mower breathed its last.

Father’s Day was on the horizon, and the couple, aware that mowing of one sort or another would be an ever-present aspect of their lives, decided to invest in a new, rugged machine. The machine was delivered, the key was turned, and within minutes, all of the early morning conversations over coffee and eggs vanished in a storm of rotating blades and blood-pumping horsepower.

The War of the Grasses began.

And thus we find them. She mows pathways. He mows everything. Each claims his/her space when one or the other of them is away. Neither of them says a word about it.

Weeks later, pondering the issue in hindsight, the woman realized that she had in fact given a Jaguar to a man who had driven a Corolla all his life—and then expected him to leave it in the garage.

She can only hope that, like most Jaguars, this one will spend more time in the shop than out of it, and her vision of grassy, camassia-filled meadows and come-hither pathways may yet come to pass.

Time will tell. ❖

Previous

Previous

This was enjoyable. Love the writing.