This is a love story. Indeed, it is my own love story. Somehow, though, it was easier for me to put it in words if I wrote as if it were someone else’s.

Twenty years ago last summer, Jan Williams stopped by Roger Rittmer’s rural home/upholstery shop to ask him for a date. At age 58, she’d never done such a thing before, but she had known Roger slightly since their high school days, and Jan’s sister, Vivien, a do-gooder, convinced her that the man needed to get a life. He had been grieving heavily for the year since his wife’s sudden death. Eventually, Jan, who also had do-gooder tendencies, agreed, and they began to make a plan. When their 84-year-old mother heard them talking, she pursed her lips and said, “So it’s come this, has it?”

Doing good aside, it more or less had “come this” for Jan. After 12 years alone, she was ready for a little decent male companionship, and Roger Rittmer was known by everyone in the small community of DeWitt, Iowa, to be decidedly decent. Asking a man for a date, though—that was a real stretch.

Vivien spoke to Susan, Roger’s daughter, who talked to her sister, Sara. The two younger women sighed, but gave their OK.

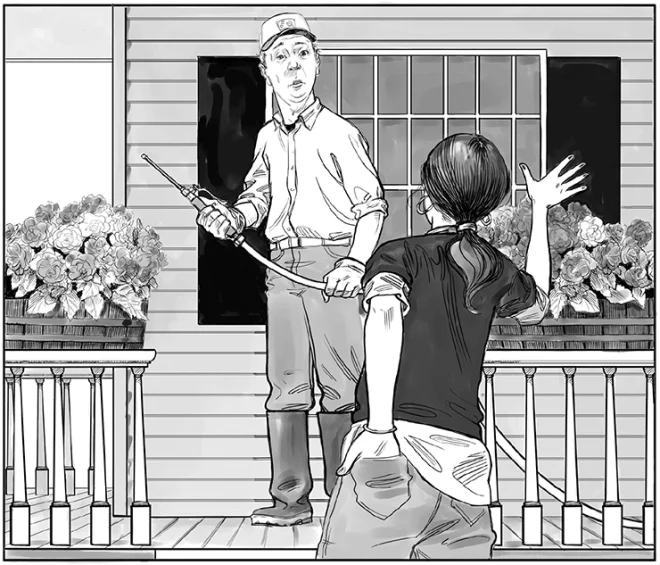

Still, when she drove out to Roger’s place one September Saturday, Jan was seriously doubting that any man was worth the deep embarrassment she was feeling. She turned on to the circular gravel drive of his rural homestead and found Roger vigorously power washing his front deck. He raised his head when he heard the scrunching of Jan’s tires—and glowered at her.

She considered driving away. But in trying to avoid looking at the wet, grumpy 60-year-old man who appeared to be threatening her with a steaming hose, she saw two custom-made cedar planters sitting on the deck. They overflowed with audacious red, orange, yellow, and pink rose-shaped flowers. She stopped the car.

“What are those amazingly beautiful flowers?” She gasped. “Oh, sorry, I’m Jan Williams, Viv Boyer’s sister.”

Roger’s glower, which had been the default position for his reasonably handsome face during his year of mourning, went away at the mention of the flowers. “Those are non-stop begonias. They always last until we get a heavy frost.”

Begonias. It registered with Jan that the flowers were obviously happy and well cared for. She remembered that while she had gone on several dates with grumpy old men over the past 12 years, she’d never known any that took good care of flowers.

Simultaneously, it registered with Roger that none of the women who had been clamoring to fill his wife’s place by bringing pie or casseroles had inquired about his begonias.

In less than three months time, the two lonely people blindsided the whole community, especially their children, by being married in a big church using Dixieland music and vows they wrote themselves.

Roger’s five children had been horrified. He explained, “Although I’ve upholstered furniture for 45 years, I’ve always been an old farm boy at heart. I love growing things, but it’s no fun without someone to help me decide what and where to plant.”

Jan had told her four dumbfounded sons, who had given up on their fussy mother finding someone after 12 years of not trying very hard, “Boys, I’m an old city girl who barely knows a petunia from a pansy, but I’m a color junky, and have unexpectedly developed a passion for begonias. Also, you may remember, I can be a little bossy, and Roger says he needs guidance.” The boys remembered.

Jan and Roger set about making their three-quarter-acre lot a horticultural showplace. That was not to be. The two were far too wide-ranging in their curiosity. Each year when the gardening catalogs came, their conversations would go like this:

Roger’d point to some exotic species, newly discovered in the Amazon rainforest, and say, “I wonder if we can grow this in Iowa.”

Jan’d say, “It’s very strange looking, honey. You should try it.” Then she’d spot an ordinary plant in a beautiful or weird color: “Oh, these sunflowers are almost black.”

Soon they laughingly referred to their place as “Rittmers’ Experimental Farm.”

Some experiments worked out better than others. Hyacinth beans dripped heart-stoppingly beautiful purple flowers and shiny pods from the split-rail fence that ran along the road. The rotten-meat smell of voodoo lilies stopped hearts, too: Roger’s upholstery customers held their noses until he tossed the stinky things into the burn barrel and put a match to them.

All the while, Roger took care of Jan just as well as he did their flowers, and Jan helped Roger decide what and where to plant—and encouraged him to upholster less and sit on the deck more.

Every year, the one garden constant was two cedar planters erupting with non-stop begonias, placed right where they could enjoy them until heavy frost.

One year Jan decided that Roger and she should enroll in the Iowa State Master Gardener classes. After that, they could identify a nameless orphan plant rescued from the K-Mart closeout table as Ligularia Dentata, cultivar ‘Desdemona.’ Still, the information about garden design never really stuck.

About a year ago, 19 years into their marriage, Jan once again offered her husband some advice. “Roger,“ she said, in the tone that he’d come to know signaled something important, “enough is enough. We are getting older than dirt. You will soon be 80, and I’m right behind you. This place has been fun, but it’s now over-run by flowerbeds, borders, and shrubs. I’m pooped, and so are you. It’s time we gave our poor old bodies a break.”

Even as Jan spoke, she grieved for the five new kinds of fern they had planted around the trees and for that pesky hydrangea that never really grew but refused to die. Then she thought of those blessed begonias. How could she ever leave the begonias?

Roger turned a bit pale around his lips, but replied, “Let me think on it.” Inwardly he heaved a sigh of relief, but he needed time to begin his own mourning: He had a few hardy cotton seeds from Louisiana to try, and a sun coleus to be started in the basement for the big new planter he built last year. Still, his aching back and knees would not miss hose hauling, weeding, pruning, and fertilizing.

“Roger,” Jan said, “Let’s don’t overthink this. Twenty years ago we married in a flash, because we knew it was right. Now what do you think’s the right thing for us to do? I trust you, and I won’t move without you.”

The two decided to relocate to a large senior facility, Ridgecrest Village, in the nearby big town of Davenport—once again blind-siding their children. “But Dad,” said Roger’s Susan, who doted on him, “you’re not sick! You’re not even old.”

“Take a closer look, honey,” he replied.

Jan’s second son, Ward, started her family’s irreverent teasing with, “It’s about darn time.”

The Rittmers downsized as much as they could, and the 14th of December was moving day. The boys from both families shoehorned Roger’s hand-built furniture into the small apartment, while laughingly agreeing that Ridgecrest Village had no idea what it was in for. The girls carried in boxes and doodads, clucking sadly over one baby jade plant and one small ponytail palm.

The Friday morning after moving day the Ridgecrest Newsletter printed an announcement:

Roger and Jan Rittmer are the new occupants of Northridge 201. The couple has a blended family of nine children. They moved here from rural DeWitt, where they were active Master Gardeners. Please make them feel welcome.

That evening, the telephone rang, and a small feminine voice asked for Roger. “Mister Rittmer, may I call you Roger? Why do all the peace lilies along the Arcade have brown tips on their leaves? They look sick. Do you think they get too much sun over there?”

After a moment of surprise, Roger replied to the unnamed voice, “Could be. I’ll come right over and take a look.” Barely pausing to kiss Jan goodbye, he set out to locate the Arcade.

So it began. The Rittmers’ new residence had more than 100 indoor plants in the common areas, all maintained by residents. They soon noticed scheffleras of every variety, an eight-foot-tall avocado tree overlooking the dining room, huge Christmas cacti in several halls, and peace lilies (doubtless donated after funerals) by the dozen. Residents kept plants in their apartments as memories—African violets “like my mother used to grow”—or for company. There was a Swiss cheese plant and a long-treasured money plant given to a woman by her late husband.

Through the winter, Roger settled in as the Ridgecrest Village de facto plant doctor, and Jan became his nurse assistant and office secretary, making appointments for house calls. The two gave the faint of heart courage to prune, feed, and water. Sometimes Roger gently advised a resident to get rid of a plant that was beyond resurrection. Jan, more plain-spoken, would say, “Just remember, dear, it’s a plant, not a child.”

Jan also rode herd on their experimental urges. She threatened to put landing lights atop a green but leafless “stick” that Roger hoped someday would be an avocado tree.

And, blessedly, Roger found the Ridgecrest woodworking ship. There they designed and he built two, four-foot planters to sit safely on the wall of their second-floor balcony. Early that spring they planted ten begonias, more than they’d ever had in the little planters back home. When the couple drank tea out on their new balcony, friends coming into the entrance down below would call up to ask, “Hey, Rittmers, what are those amazingly beautiful flowers?” Roger always grinned and replied, “Those are non-stop begonias. They will last until we get a heavy frost.”

Non-stop and long-lasting. Like Jan and Roger. ❖

Previous

Previous