Elementary school is supposed to be a special time in our lives. However, as far as I can remember, my most fond memories of elementary school were recess and fire drills. Other than that, I absolutely hated school. I despised it. Every day was like being locked in a prison.

You might wonder how I ended up being an elementary school teacher. Some days I certainly do.

It wasn’t all my school’s fault. I know that I was a real knucklehead. I was squirrely. I had difficulty paying attention and following directions. My report card actually used the phrase, “he

has ants in his pants.”

My attraction to recess and fire drills was that they were the only times we were allowed to go outside. If you were to ask me what I liked about going outside at these times, the eight-year-old in me would have said, “Because it is fun and I forget that I’m at school.”

In education, there is a point that we are all trying to reach, when the teacher is able to connect with students so that learning blossoms. It becomes no longer a chore or prison-like, but rather intrinsically rewarding and even fun. So much fun that you can forget that you are learning. The difficult part is that what works for one student doesn’t necessarily work for another. The trick is finding the right approach to plant that seed in each child.

I share this with you, because, as a student, this never happened to me. Not once. Ever. My seeds never took root. So maybe I became a teacher for the sake of the squirrely kids. My motto would be, “No knuckleheads left behind.” I wanted to make their education engaging and fun. How was I going to do this? By taking them outside as much as possible.

On my first day, I went to my principal to tell her my plan. She said, “Outdoors? Why?” Unfortunately, the 8-year-old inside me answered, “Cause they’ll forget they’re at school.” She wasn’t thrilled to hear that.

I needed to show the benefits of taking kids outside. I conducted a review of as many studies as I could find on the subject. And I have to say that there is overwhelming evidence that states that the more kids are outside, the happier they are, the healthier they are, and the smarter they will be. They score higher on standardized tests. They have less stress and anxiety.

Students who spend time outdoors also show a stronger connection to the STEM subjects. They are more likely to form a strong bond with the environment and more likely to fight for this resource.

This was great news, however, what about my students? How could I help them make that connection?

I looked at my third graders. Third grade is filled with knuckleheads. “I know how we can get outdoors!” I said to myself. “Let’s study the pioneers!” It worked—giving us chances to do something outside almost every day.

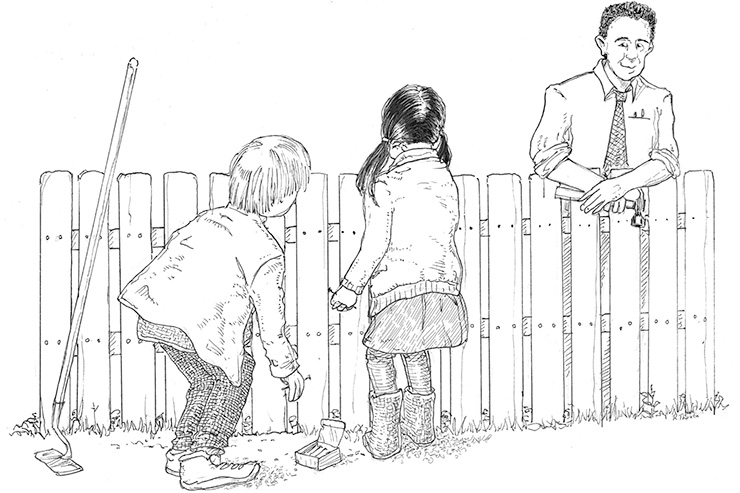

At the end of our unit, we had a special Pioneer Day. The entire day was spent outdoors working, playing, and learning just as the early Americans. We studied under a tree on blackboard slates. We mended the wooden fence around an old, small school garden area. We gathered firewood and cooked lunch over a campfire.

After lunch, we came together in the garden to start digging and hoeing a garden that, next Spring, would be capable of sustaining our pioneer community. Then I brought out some mature squashes and dried ears of corn, and we worked on harvesting seeds to save from those.

Just then I noticed that we were wicked late for dismissal. We hustled the kids out of the woods and marched back down the hill. I could see buses and parents lined up waiting for us. Some of the parents looked pretty annoyed.

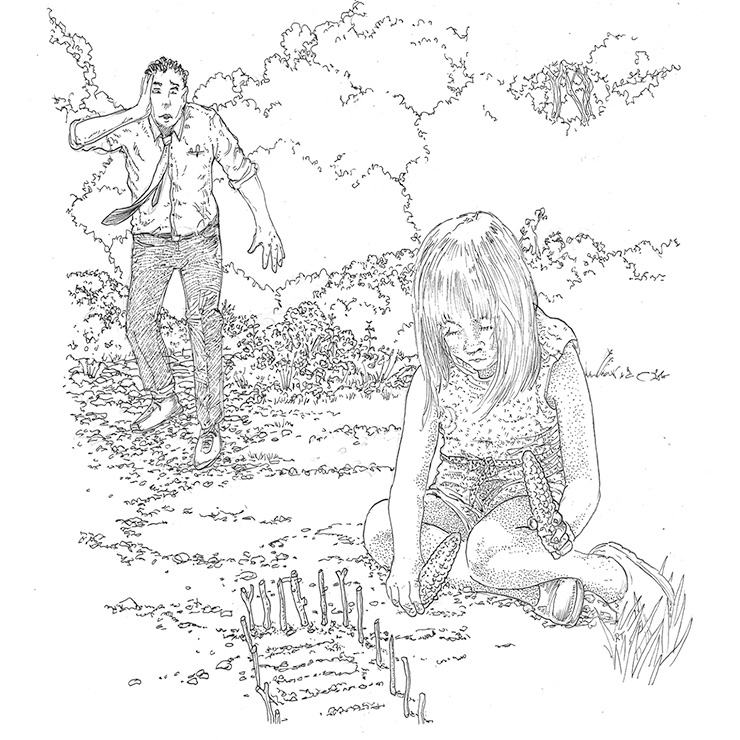

As we got back to school, I started counting heads. Remember my motto: “No knuckleheads left behind.” There was one. (Well, I was one, too, for not counting heads before we left the garden.) We were missing one kid, the biggest knucklehead in the class. She is a very sweet girl, but definitely has “ants in her pants.”

I raced out of the school and charged up the hill to the woods. With each step, I grew more and more angry. How could she not have seen us all leave? How could she not have paid attention? Why couldn’t she ever follow directions?

I stormed into the garden. There she was sitting among the freshly plowed soil playing with two ears of corn, pretending that they were little pioneers and making them talk. Next to them was a miniature garden with a tiny fence made out of sticks: an exact replica of our larger garden space. She saw me approach and could tell how angry I was. She looked up in fear and said, “I’m so sorry, Mr. Cooper. I was having so much fun, I completely forgot that we were at school.” ❖

Previous

Previous