I served as a British soldier for more than two decades. When I was discharged, I was physically fine but—as I realized later—mentally broken. Things I’d blocked out at the time now gave me nightmares, recurring nightmares. But I refused to accept help for another two decades.

By then single and in my early 50s, my hobbies were drinking heavily at home until I fell asleep, waking up, and doing it again.

The thought of ending everything crossed my mind—more than once.

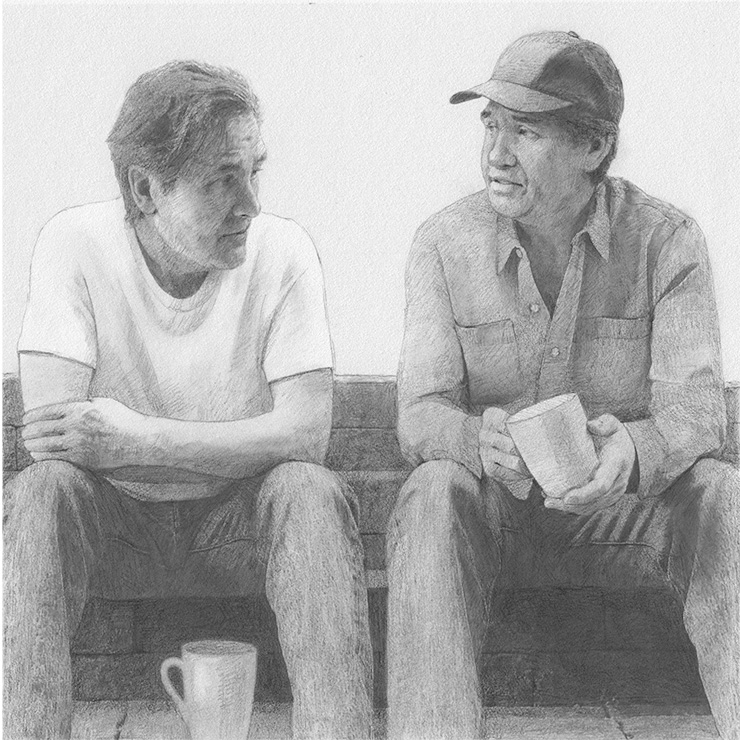

Then one day, my daughter Chantelle arrived, along with Dave, an old military friend. Chantelle spent the afternoon cleaning the house that I had let become a pit. Dave spoke gently with me for a long time. My daughter kissed me goodbye and left, promising to return soon. But Dave stayed. He made two coffees and he and I sat quietly on the back step in the warm, late afternoon.

I relaxed. To have two people caring for me without my even asking for it was something I’d not felt in a long while. It felt good.

Dave looked out at the three-feet-high grass and weeds in the back “Is that a garden?” he asked.

I shrugged. “Well, I guess. I mean it used to be.”

He told me about his life after his own breakdown, his ongoing fortnightly visits from a veterans’ psychologist, and how working in his garden had really helped him.

“I’ll tell you what, Bob. I’ll come back tomorrow, and we can start cleaning up the garden. We’ll start slowly, just an hour or so. You’ll be surprised, gardening is great—and you’ll see instant results.”

I agreed, but had no intention of doing anything of the sort. Gardening is for old people, I said to myself.

The following morning my doorbell rang, way too early. Oh, well, I didn’t have to go far to answer it—I’d passed out drunk on the settee. I groggily opened the door and was horrified to see Dave, with all manner of gardening equipment in a wheelbarrow behind him!

“Good morning, sir,” he said, politely. “It’s 0800. I believe you and I are on weed patrol today.”

It took me an hour or so to wake properly, shower, and get ready to do some work. Dave patiently nurtured me, making me eat and drink something. As I chewed my toast, Dave set a pieceof paper in front of me, his list of how we could make the area both productive and nature-friendly. The first job, he said, would be to cut the grass in an area about three metres square. We’d then dig it over and plant a row of radish seeds. Dave explained that the work would be hard, but that I’d see returns, both today and in a few days as the radish plants started to sprout.

He was right on both counts. Digging ground that was full of weeds and hadn’t been turned for a few years was hard, hard indeed. I’d grown unused to physical labour and had to stop often. But by late afternoon, we’d removed all the weeds and turned over all the soil. And, I had to admit, I really could see immediate change.

As time went on, I started noticing other things, too. I saw veggies starting to grow, but also honeybees. I saw weeds—which I removed as soon as they dared poke their heads above ground—but also birds. Oh, they’d been there, but I’d been inside throwing alcohol down my throat as fast as I could. I decided to help take care of them, too. I built an insect hotel, a bird feeder, and a few bird boxes.

Dave and I had planned to have 60 square metres of garden in vegetables. The plan was to do no more than ten metres for the first year, but we’d cut out all the foliage in the rest, then I’d keep it mowed. Dave asked me what I wanted to grow and smiled at some of choices.

“Asparagus? That takes three years. But we can make a bed and plant them this year.”

“Carrots? They may be a bit difficult this first year. Your tilth isn’t fine enough.”

“What about melons?” I begged. “I’ve always loved Charentais melons. You know, that deep-orange, tender French cantaloupe? I’d like to grow that most of all.”

“Melons? In England? I’m not sure it’s warm enough for long enough, mate.” He looked at the disappointment in my face. “But why not? Let’s give it a try.”

That first year, I had mixed results in my garden. Some things (radishes!) did well; many (my melons) did not.

But I had very positive results in my life. I liked working physically in the garden. I enjoyed being outdoors and learning how to care for plants. I spent a couple of hours pretty much every day in the garden. I lost weight, gained some colour in my cheeks, and felt my muscles becoming stronger.

And I stopped drinking alone at home. When Dave came round, which he did often, we always had a beer at some stage, but only one. My life changed in so many ways, all for the better.

Over the next four years I learned to have the patience and skills a gardener needs to grow tomatoes, leeks, spuds, garlic, and more. My diet improved vastly—all that homegrown produce! Relationships improved as I learned to take better care of others as well as myself.

But every year, every single year, I failed to grow a Charentais melon. I coddled the plants the way a mother hen does her chicks, even starting them indoors in a greenhouse to get a jump on the season—but no luck.

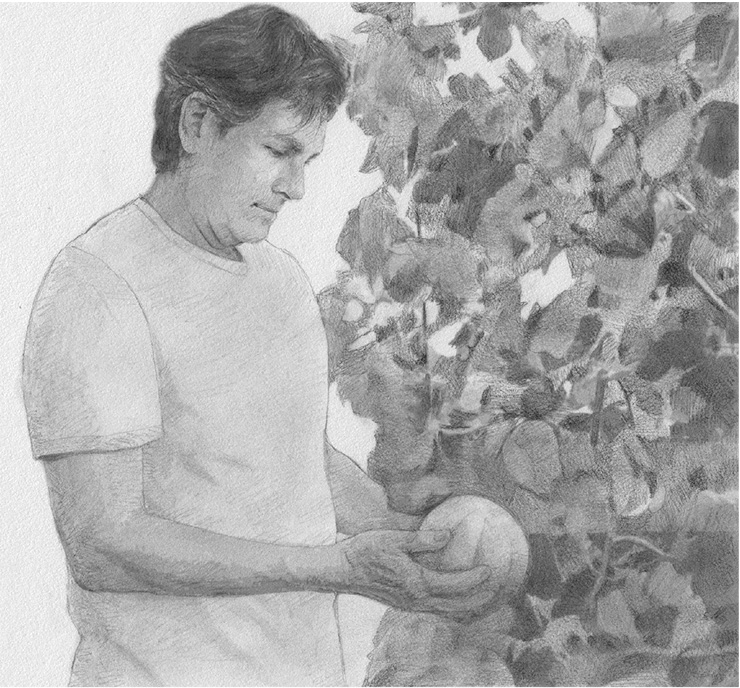

That fifth year, this year, I wasn’t going to accept defeat. I had to raise a Charentais. It felt like it would validate all the work and progress of my life.

That Spring, holding the small seeds in my hand, approaching my soil-filled pots, I spoke sternly: “This year you’re going to give me fruit.”

I was going all out for success. Four pots, four seeds per pot. My own homemade well-rotted compost, a heated propagator indoors to start them off.

Four days after planting, I saw the first little green shoot fighting through the dark earth. After 10 days, 11 of the 16 seeds had sprouted. I kept all of them—instead of just the strongest ones—and moved them all into individual pots. Eleven terracotta pots sat on a south-facing windowsill, above the radiator in the warm front room. Once the plants were strong enough and I was certain the worst frosts were over, I took them out into the greenhouse. It hadn’t been heated before, but this year, I’d installed a heat capture system. The melons were placed high up on a shelf to ensure maximum warmth.

And then disaster. One night I fell asleep on the settee watching gardening videos online (oh, the irony!) and didn’t close the door and windows of the greenhouse.

That night there was a sharp late frost. I lost more than half the plants.

In the next few weeks, a few more fell by the wayside. But by late Spring my three remaining plants were growing strongly, so I started the hardening off process: days outside against a southfacing wall, then back in the greenhouse at night. This process took over a week before I finally planted them into their final site, each plant with a glass cloche over it that was closed each night and opened during the days.

The day I saw the first melon flower was a big day. I was now down to only two plants, one having been destroyed by slugs. I’d gotten to this stage before though, I’d even had fruit before, but they’d never grown larger than a ping-pong ball. But this year … Dave came round to share my excitement. We had a light lunch, a fresh garden salad, picked in front of his eyes, washed, and popped on the plate with, yes a homemade mayonnaise.

The flowers multiplied, then fruit appeared, tiny at first. That year Summer was long and hot. I went away for a few days to see Chantelle—and returned to find one plant dead. I suspect the neighbour’s cats played with it, but I had no proof. The other—the last—plant was pushing ahead and had four large fruits. I placed each one on a piece of slate to protect it from rot and spent hours cosseting them in any way I could.

Finally, I knew the day had come.

I called Dave: “Come round tomorrow, Dave. The fruit of my labours will be tasted. We’ll have port and melon to start.”

He came in the afternoon. As we sat over cups of coffee before going out, words I’d been looking for for a long time finally spurted forth.

“Dave, thanks. Five years ago, your visit with Chantelle changed my life. I would have slowly drunk myself to death. I know it was she that called you, but you didn’t have to come and you certainly didn’t have to come back. You turned my life around. I’m sure you know, but just in case you don’t, I’m telling you.”

He tried to protest, but we both knew what he’d done for me.

I took my knife and we walked to the melon plant. The Charentais lay there, the morning dew long since gone, the remaining leaves yellowing. I cut the stem of the largest one, took it to my outdoor table, sat down with Dave, and sliced. The warm, sweet aroma of a fully ripe Charentais rose to our nostrils.

Back in the day, as younger men, we used to sit in the Sergeants Mess and eat a port and melon starter. A couple of decades later, older, heavier and with less hair, we sat in my garden, the late Autumn sunshine warming our backs as we looked at the recently harvested field behind the garden, and enjoyed the best port and melon starter ever.

The steak on the BBQ was slowly cooking, my homegrown spuds, tomatoes, and onions were roasting in the oven.

And life, like our melon, was very sweet. ❖

Previous

Previous