Read by Matilda Longbottom

“But tomorrow may rain

So I’ll follow the sun.”

—The Beatles

What do you believe?

Individually, most of us know pretty much where we stand on life’s bigger issues—and similarly on life’s smaller, though even on these we may not agree, which is what leads to family ructions over things like toothpaste squeezing and cats on the bed.

Publicly, though, belief gets a lot more complicated. The news these days—no matter what your political sympathies—can’t help but make you wonder who truly believes what. Who’s telling the truth? Who’s sincere? Who’s lying? Who should we believe?

Sooner or later we have to decide.

Which brings me to gardens. And sunflowers.

Sunflowers—along with corn, beans, peppers, potatoes, and cotton—are native to the Americas, likely cultivated more than 3,000 years ago by the indigenous people of Mexico and the Southwest. It was these farmers, archaeologists believe, who changed the sunflower from a runty, multi-branched wildflower to the behemoth grown in fields and gardens today. The Spanish conquistadors brought the sunflower—along with a lot of other loot—to Spain, from where it spread through Europe as an ornamental. Scientists pounced upon it: Nicolás Monardes, in his Joyfull Newes Out of the New Founde World (1577), gave it an enthusiastic description under the heading “The Hearbe of the Sunne.” He also added helpfully, “It is needefull that it leane to some thing where it groweth or else it will bee always falling,” a stricture that still applies today.

Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia, first happened upon sunflowers in 1697 in Holland. Peter was touring western Europe at the time, learning navigation and shipbuilding techniques with an eye to modernizing the Russian navy. He was traveling incognito and working as a carpenter in the Dutch shipyards—though just how incognito he was is a matter of debate, since he was accompanied by an entourage of 250 and stood 6-ft., 7-in. tall in his socks. He sent sunflowers home, and in doing so, changed the Russian economy.

Sunflowers—Helianthus annuus—are named both for their flashy yellow flowers and for their sun-tracking behavior. Botanical groupies, sunflowers follow the sun, slowly tilting their heads from east to west over the course of a day, then returning to face east again overnight, ready to start the whole process over again. Scientifically, this behavior is known as heliotropism and in sunflowers it occurs because auxins—plant growth hormones—accumulate in greater quantities on the side of the sunflower stem opposite the sun. The hormones prod the cells on that side of the stem to elongate and multiply, which in turn causes the flower head to tilt.

According to recent research, there’s even more to it than that. Sunflowers, it turns out, have circadian rhythms—that is, a 24-hour internal clock determines their east-to-west and back again daily motion. Put sunflowers in a greenhouse under artificial light and try to make them adjust to a 30-hour schedule and they’re not having any.

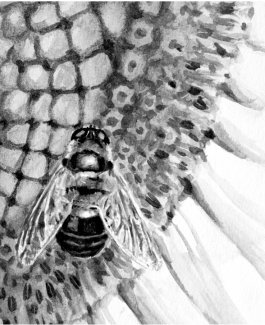

There’s a reason for all of this sun-following, other than frivolous beach-bunny-like basking. Sun-facing flowers are warmer and bees like warm flowers best. Scientists—by cruelly yanking sunflowers around and making them face the wrong way—found that sun-facing flowers are visited by five times as many pollinating bees.

All that back-and-forth sun-tracking behavior doesn’t last forever. It only happens with youthful sunflowers. Once a sunflower reaches adulthood—by which time it can be a towering 10-foot-tall plant with a flower up to a foot across—it ceases to waffle. Adult sunflowers settle down and stay pointed determinedly toward the rising sun in the east. Once they’re grown-ups, sunflowers stay put.

Tsar Peter’s sunflowers, back home in Russia, were wildly popular. Russian sunflower growers soon developed bigger and better cultivars both for eating—Russians to this day love to snack on sunflower seeds—and for oil. The passion for sunflowers was encouraged by a quirk of the Russian Orthodox Church, which forbade the consumption of butter, lard, and vegetable oils during Lent—with the notable exception of sunflower oil. In fact, in one of those twists of fate so common in the garden world, by the 19th century, gargantuan and nutritious Russian sunflowers were being imported back into the Americas.

Today the prime producers of sunflowers worldwide are Russia and Ukraine—the two collectively account for an annual 30 million metric tons of sunflower seeds and over 70 percent of the world’s sunflower oil. In Ukraine, the sunflower has always been a national symbol. Since the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February of this year, a display of sunflowers has come to be a global signal of solidarity with the Ukrainian people. The Washington Post calls them “a symbol of resistance, unity, and hope.”

Sometimes what we grow in our gardens means more than we think it does.

I believe that our beliefs aren’t set in stone. We’ve always got time and options for growing, for learning, for experiencing, for changing our minds. But sooner or later, when it comes to right and wrong, we have to come down on one side or the other.

We have to decide what we believe and who we choose to listen to.

And that’s when—like those sunflowers—we stop shifting with the sun, dig in our heels, and face our east. ❖

Previous

Previous

This is another example/tidbit added to my love of sunflowers. TY