Read by Matilda Longbottom

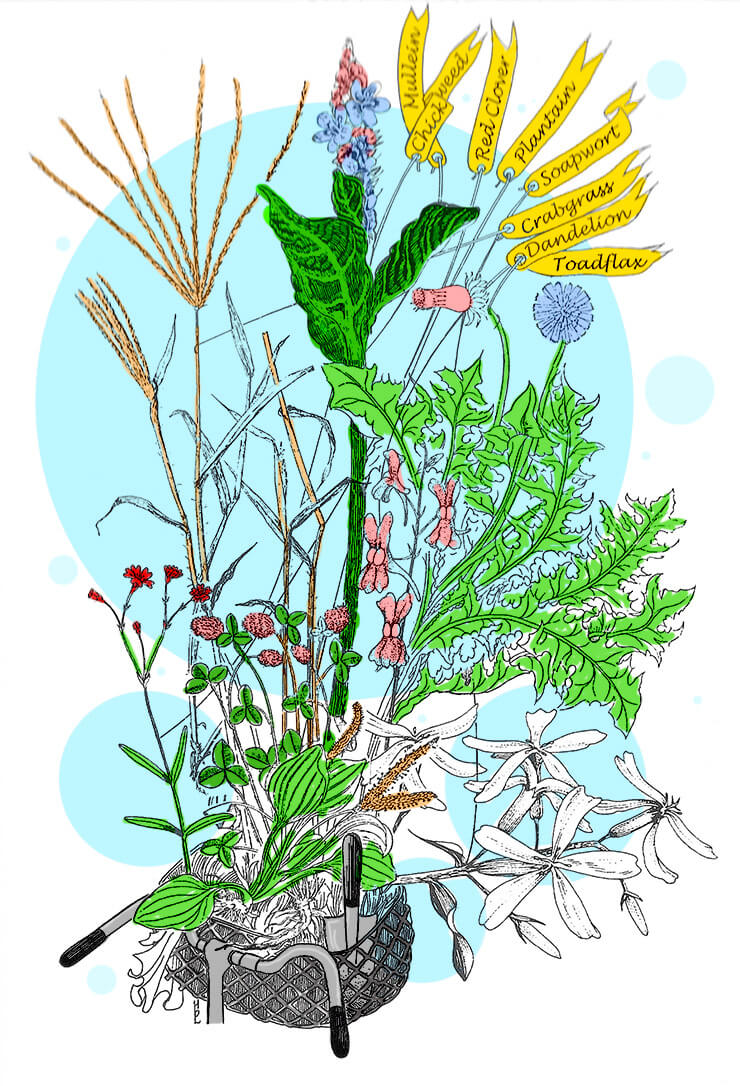

I found my bicycle in a flea market. It isn’t the racing kind on which you bend double and whizz as fast as you can, helped by a multiplicity of gears. It’s green, quite heavy, with a nice wide saddle, a high handlebar, and three gears. It has a basket, too, in which I always keep a trowel. Other cyclists zooming past seem startled but friendly when they encounter me.

One gallant young man even stopped recently to ask if I was “all right.”

I don’t know if he was concerned because I was not equipped with those tortuous tight shiny shorts and hard helmets they all seem to wear, but a comfortable cotton frock and hat, or because I had dismounted to inspect the ditch, but I thanked him anyway. I feel sorry for cyclists who don’t have a bicycle basket. Mine has all sorts of passengers. Often, in the spring, I find a turtle in the middle of the road, and I carry it to a suitable stream or pond.

I have to keep a large red handkerchief in my basket, too, because turtles (or toads) are very restless passengers, and you have to tie them in quite tightly, or they simply climb out and fall back onto the road. I once picked up a praying mantis, and after I had deposited it in a wonderful bush, sure to be full of aphids, I found it the next day on the road again, squashed.

My husband said it was a different praying mantis, but I think not. My passengers are more apt to be plants than animals—because the trowel is carried with a purpose. Let me make it clear that I do not believe in digging up wild flowers. Indeed, it is a legal offense. Almost all gardeners disapprove of and mourn the loss of rare and beautiful flowers that are dug up by those who want them in their yards.

Most of the flowers die anyway and it is both safer and better to buy them from a reputable nursery that raises them. We know that. Why then do I carry a trowel in my bicycle basket? Well, just as I rescue animals, I sometimes rescue plants. I may be wrong, but I do this with a clear conscience. The ditches each side of the roads where I ride are scraped regularly and sometimes sprayed, as well. If I see a stray Jack-in-the-pulpit, or wild geranium, or Solomon’s seal, it comes home with me in my bicycle basket.

Once, there was a particularly fine stand of Solomon’s seal beside a mailbox along the road. Someone had started to dump old leaves and debris on top of them. So, one quiet afternoon, I pedaled to the spot. That time I took a bag as well as the basket because I intended more than a single swift transplant. There was, funnily enough, a large notice on the mailbox to say that the house was electronically protected from burglars—so I propped my bicycle against it.

From the look of things, everyone was out making money to keep up the establishment. I dug busily, getting quite hot in the process and not noticing much until I was interrupted. “May I ask what you are doing?” said a very smart woman who had just come out of the house. I hesitated. I do pride myself on being an honest person. “Well,” I said, “actually I’m stealing your Solomon’s Seal.” I showed her. It was early in the year and they hadn’t quite unfolded.

The popular name Solomon’s Seal is generally thought to refer to the fact that the underground stems bear seal-like scars where branches from former years originated (each year the underground stem grows longer and the new plume from it gets higher. I have some which reach up to my shoulders.) Gerard says the name refers also to the fact that the roots “are excellent good for to seale or close up greene wounds.” He refers to its chief virtue delightfully as the ability to cure “in one night or two at the most, any bruse, blacke or blue spots gotten by fals, or womense wilfulness, in stumbling upon their hastie husbands fists, or such like.”

I was going to explain all this to my new acquaintance, though, to be sure, she looked as if she could cope with most kinds of hastie husbands. But she was evidently in a hurry. “Oh, that,” she said. “As long as you don’t take any flowers.” She pointed to a little group of impatiens huddled against the gatepost. I was truly able to assure her that I would not dream of taking the flowers, and I thanked her profusely for her Solomon’s Seal.

Still, while not agreeing with her, I certainly understand the woman’s behavior for, generally speaking, what we value are classed as “flowers” and the rest dismissed as “weeds.” And it is a changeable definition.

Many of our present weeds were deliberately brought as passengers to America and carefully cultivated as useful plants. Bouncing Bet, or Saponaria, was used for laundering and treating skirashes. It was recommended for poison ivy—a plant that European settlers (including, much later, myself) had never encountered. The soapy lather it makes in water is still considered the safest way to clean fragile old textiles and tapestries.

Today, its pink and white flowers grow freely along roadsides at the edges of fields. Dandelions were cultivated for their greens and diuretic qualities (they are known as “pis-en-lit” in French). Chickweed was a common home cure and, in Elizabethan England, used to feed poultry.

Lafayette, Washington’s aide in the Revolutionary War, is credited for introducing red clover for animal feed, and William Penn imported grass seeds from England to make lawns. (Much of newly settled America was basically forest land and naturally low on pasture and forage plants.)

Crabgrass, which is a form of millet, was imported by immigrants from Central Europe as a basic food grain. Mullen was another cultivated medicinal plant whose soft, woolly leaves were used to make poultices. Plantain’s mucilaginous juice was valued to heal cuts.

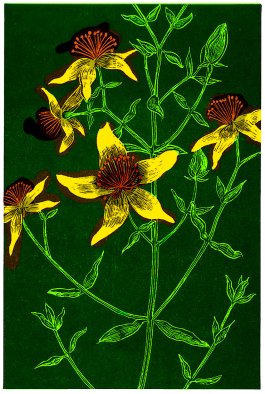

Toadflax was used for dye and as a fly poison (by setting out saucers of milk in which the plants had been boiled). St. John’s Wort was introduced as a plant of supernatural powers used for healing wounds, and the perforations in the leaves were associated with the perforations of Christ’s hands upon the cross, which supposedly reinforced its healing powers.

By the time of John Bartram, many of these useful plants were already out of control and considered weeds. In a letter to Peter Collinson in 1759, John Bartram lists “Introduced Plants Troublesome in Pennsylvania Pastures and Fields.”

By now, Toadflax, or Butter and Eggs, is called “ye most hurtfall plant in our pastures.”

Some people, he says, “have roled great heaps of logs upon it and burnt them to ashes whereby ye earth was burnt half a foot deep yet it put up again as fresh as ever . . . it was at first introduced as a fine garden flower but never was a plant more heartily cursed by those that suffers by its incroachment.”

By now, St. John’s wort is a “very pernicious weed” which gives “Scabed” noses and feet to cattle, “especially those that have white hair on their face and legs.” Mullein is “easily destroyed with ye plow or sithe.” Of saponaria, he says, “with care we may keep it under.” Dandelion he calls “very troublesome.” Of thistles, he says, “A scotch minister brought with him A bed stuffed with thistel down in which was contained some seed ye inhabitants having plenty of feather soon turned out the down and filed the bed with feathers ye seeds coming up filled that part of the country with thistles.”

All in all, he calls “most of ye English plants that bath escaped out of our gardens . . . very much to our detriment.” So many of our troublesome weeds originated from introduced plants that we are apt to forget that weeds are sometimes native plants and that not all introductions were disastrous. Indeed, after listing the introduced weeds, Bartram goes on to describe “some of our native plants that is very troublesome in our fields and medows and is with difficulty eradicated.”

Any plant that grows where we plan something else is, of course, “troublesome,” whether it’s native or an escaped introduction. There’s a development I bicycle past where, every spring, a heart-rending little patch of Johnny-jump-up appears. The grass is maintained by a lawn company and every spring, soon after I have admired it, it is mowed down.

Naturally, before that happens, I stop and dig up as much as will fit into my basket. Johnny-jump-up came over with the settlers and was associated with many curative powers, from that of “heart’s ease” for it was used as a love philtre to curing “the French disease” (one hopes the latter was not the result of the former!).

Many of its names are associated with love: “love-in-idleness”, “peeping Tom,” and “ladies’ delight” are just some of them, and it ended up as the ancestor of the “pansy” or “Pense” which supposedly had the power to turn the thoughts of one’s lover towards oneself. It’s nice to think of the Puritan settlers tucking a few seeds into their baggage to alleviate their hardship and brighten their lives.

“God send thee hartes-ease,” wrote an Elizabethan. “For it is much better with poverty to have the same, than to be a Kyng witl- a miserable mynde … Pray God give thee but one hand-full of heavenly hartes-ease, which passeth all the pleasant floures that grow in this worlde…. ”

I can’t vouch for all its virtues, but it surely, like all the passengers in my bicycle basket, cheers the soul. The fact that I have rescued it maybe adds a little to my pleasure, also. Gardeners, like lovers, are a fickle bunch: We coddle plants and carry them tenderly across oceans. Then, when they respond by flourishing, we call them invasive and want them no longer.

Oh, dear. From our point of view, they hardly ever seem to get it right. ❖

Previous

Previous