There’s a lot to be said for solitude. Henry David Thorough once wrote, “I have never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.”

Sometimes the joy of gardening isn’t in the sun-kissed tomatoes and tender basil on your plate for lunch, or the pleasure you get out of creating your own soil and feeding the bees with a pollinator garden.

Those are benefits for sure; I’ve still never had a tomato better than one grown in my own garden snipped fresh off the vine.

But what I love about gardening is the solitude; the oneness experienced when down in the dirt. The garden is a place I can go to shake off a bad vibe or get a new perspective. It’s where I’ve gone to come back from an argument with more understanding.

In Remedial Weeding, the piece below that I’m sharing with you today, Becky Rupp compares pulling weeds to yanking up “the bureaucrats, the traffic jams, the nightly news, and that nutcase down the road who writes those appalling Letters to the Editor.” Her humor is softened with the gentle reminder that gardening in solitude is what we all need to go back to the world of people as the best version of ourselves.

When you read this piece, you’ll be reminded of the true joy of gardening, and I hope you find it as nourishing as I have.

Discover 7 top tips for growing, harvesting, and enjoying tomatoes from your home garden—when you access the FREE guide The Best Way to Grow Tomatoes, right now!

Finding the Joy of Gardening in Solitude

The following joy of gardening story comes from The Weeder’s Reader: GreenPrints’s Greatest Stories. Gardening stories like these always give me a good sense that I am on the right path and have chosen a worthwhile “hobby”. I hope you’ll enjoy it too.

Remedial Weeding

Feeling stressed? Gardeners know the cure.

By Becky Rupp

Last week, while driving home from the library at four o’clock in the afternoon, I blocked the driveway of our local Dunkin’ Donuts restaurant. I didn’t mean to block the Dunkin’ Donuts restaurant; there was a panel truck in front of me and somewhere ahead of that a traffic light had inopportunely turned red, leaving me stranded in front of a bubblegum-pink sign that said ENTRANCE. These things happen. You could think of the whole incident as a sort of malicious vehicular game of musical chairs.

This might have been all right—small-town Vermont is a reasonably laid-back environment; most of us can wait out a red light in relative tranquility—except for a woman in a gray Chevrolet who wanted to turn into the Dunkin’ Donuts driveway now. She honked, and then honked again, louder and longer. I made apologetic faces, indicative of my inability to budge; and she rolled down her window, screamed unprintable names, and made finger gestures.

Ten seconds later the light changed.

She roared into the Dunkin’ Donuts. I went home and weeded the lettuce.

Sometimes the thing I like best about the garden is that there’s nobody else in it.

Jean Paul Sartre, in a disillusioned existential moment, said that “Hell is other people,” and he may not be far wrong. People are aggravating. They shove; they yell; they call you on the telephone in the middle of supper and solicit things. They point out tactlessly how superior their children are to your children, and expect you to be nice about it. They borrow books and never give them back. They tailgate.

And sheer numbers of people are intimidating. Our brains, still psychologically stuck in the Stone Age, can’t really cope with any group bigger than a hunter-gatherer tribe. Cram us into Tokyo, Calcutta, or New York—even Bennington, Vermont, at rush hour, when the schools let out—and things get stressful. Look at rats: Inordinately crowded, they have nervous breakdowns, curl up in corners, and chew their paws. Daniel Boone, who had a strong sense of self-preservation, used to get restless the minute he could see the smoke of a neighbor’s cabin.

There’s a lot to be said—at least in measured doses—for solitude. Percy Bysshe Shelley, who had a fraught life, said that he loved tranquil solitude. John Milton, who had marital troubles and three rebellious daughters, called solitude “the best society.” William Wordsworth, who was fond of wandering lonely as a cloud, called it blissful. “I have never found the companion,” wrote Henry David Thoreau, “that was so companionable as solitude.” You can imagine him saying it as he pottered about—peacefully solo—in his bean patch.

I have friends who, in emotional extremis, favor bubble baths, five-mile jogs, psychotherapists, or bottles of gin. I, however, have always favored weeding, solitary weeding. Gardens, along with vegetables and zinnias, dispense calm, comfort, and perspective. There’s something soothing about green and dirt; as you crawl about by yourself, pulling up invasive stuff in the cucumbers, the jagged disruptions of even the most dreadful days, begin to smooth themselves over. A garden exemplifies placid common sense. Give it a chance and it takes you outside yourself, reminding you that—for all your petty fretting—the planet is still spinning along.

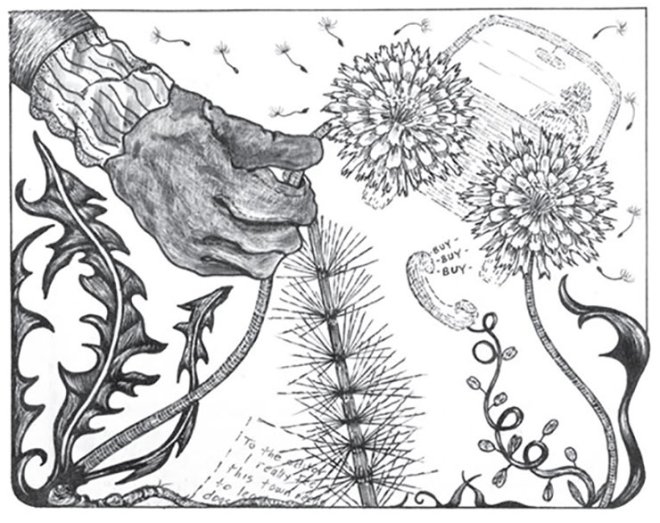

And there’s an unmistakably remedial aspect to weeding. It’s a cathartic activity—even, properly practiced, a sort of vengeful voodoo. Yank up crabgrass, peppergrass, knotweed, and horsetail; tear out (cautiously, with gloves) the awful stuff that my field guide refers to as Horrible thistle; obliterate hawkweed, ragwort, and prickly lettuce. Each pestilential handful, metaphorically speaking, is a stumbling block in your daily path. Yank up the bureaucrats, the traffic jams, the nightly news, and that nutcase down the road who writes those appalling Letters to the Editor.

Weed long enough and you’ll feel better. In fact, you’ll even start to come around on the people thing. Some people, after all, are your loved ones: your spouse, your children, your dearest friends, people without whom your life would be sad and dull, devoid of laughter, conversation, hugs, and shared peanut-butter toast. We need each other. No person is an island; and, after an hour or so interacting with chickweed and dandelions, this begins to look once again like a positive proposition.

Which brings me back to the woman in the gray Chevrolet. I’ll doubtless never know what drove her to the point of shrieking at a perfect stranger inadvertently blocking the Donut lane. It could have been whining children, a delinquent babysitter, nasty neighbors, a surly husband, or a tyrannical boss. Her day could have been beset with tax collectors, broken pipes, and flat tires. She probably thought she needed a doughnut.

But I can tell you what she really needs. She needs a garden. ❖

By Becky Rupp, published originally in 2004, in GreenPrints Issue #58. Illustration by Blanche Derby.

Did you enjoy this joy of gardening story? Please tell us if it renewed your day and any personal stories that this invoked for you.

Discover 7 top tips for growing, harvesting, and enjoying tomatoes from your home garden—when you access the FREE guide The Best Way to Grow Tomatoes, right now!