Of the many harmful garden insects, a number of them crawl unnoticed toward a feast of garden fruits, vegetables, flowers, and herbs. They hide in the soil, under dense foliage, and even within the stems and stalks of our plants.

Sometimes, if you’re lucky, you can catch them. Most harmful garden insects leave telltale signs that alert us to their presence: distinctive holes in leaves or secretions that give away their location. Others hide so well that we may never know they’re around. Until it’s too late, that is.

Even when we don’t recognize the presence of harmful pests, the author of today’s story, Barbara Kodner, wonders if, perhaps, our plants know. In A Knowing Peach Tree, Barbara asks if trees can “sense trouble coming? Can they tell when they are healthy or desperately ill?”

Barbara’s theory is that, yes, a tree does understand when its time here on earth is coming to an end. She also believes that they plan for the inevitable in ways we may not notice or understand. Ultimately, Barbara’s peach tree can’t talk, so we’ll never know exactly what was going on behind the scenes in this story. Even so, she gives us a wonderful way to think about how much more trees and plants may know than we realize.

Harmful Garden Insects May Not Give Us An Abundant Harvest, But They Can Give Us Stories.

This story comes from our archive spanning over 30 years, and includes more than 130 magazine issues of GreenPrints. Pieces like these that imbue the joy of gardening into everyday life lessons always brighten up my day, and I hope it does for you as well. Enjoy!

A Knowing Peach Tree

How much do they understand?

By Barbara Kodner

Can trees sense trouble coming? Can they tell when they are healthy or desperately ill? I’ll let my peach tree answer. But first, a glimpse at my horticultural history.

My husband and I have always loved gardening, even when it didn’t make practical sense. As a kid, I tried to establish a strawberry patch in the backyard with my dad’s help. My husband grew tomatoes and peppers as a kid with his mother. During the early years of our married life, we attempted to grow tomatoes behind our apartment building, and we even tried to grow mushrooms in a closet. Finally, after eight years of apartment living, we bought our first home in a St. Louis suburb. The house fulfilled the needs for our family of five, and the backyard held promise for extensive gardening with its flat, sunny expanse of soon-to-be-uprooted grass.

We moved in in August, and discovered a cherry tree that was finished for the season, along with vines and vines of Concord grapes at their peak. The children helped me pick the grapes, while my mother-in-law taught me how to preserve our crop in jams and jellies. The idea of producing food on our little patch of land had taken root. Seed catalogs and gardening books were our constant Winter companions as we dreamed of next Spring’s planting.

We designated the farthest corner of our one-third acre for the vegetable patch. Lettuce, tomatoes, corn, beans, spinach, asparagus, even okra and kohlrabi enriched our meals and taught our children to enjoy vegetables (except eggplant, of course). Then we decided to add more fruits—entire trees of fruit.

We chose a spot behind the garage for our “orchard.” A plum tree and an apple tree struggled to satisfy us, but the peach tree—now, there was a tree to remember. Our one dwarf peach tree exceeded all of our wildest expectations.

For the first few years, as the tree settled in, its crop was sparse. By the fourth year, the peaches were abundant enough to grace our breakfast cereal and ice cream desserts. By the sixth year, peaches filled pies and canning jars. By the end of that Summer, I noticed that my neighbors usually weren’t home when I went to their doors for a second or third time to share our bounty.

The seventh year of our peach tree was the most memorable. That year, the outpouring of sweet, juicy, delicious peaches from our tree reached its apex. The first few days of harvest weren’t remarkable, but suddenly the tree exploded with ripe rosy fruit. I spent days canning peach jam and jelly. My children ate peaches every day. My neighbors took home bags of peaches.

Finally, one day, I picked so many peaches with my son and two daughters that I decided to make peach pies, but I knew that I’d need lots of help. Throughout that day, my mother, mother in-law, grandmother, and daughters washed, peeled, and sliced peaches until they were covered with peach fuzz and juice. My son walked to the grocery store several times for more flour and sugar. I mixed and rolled what felt like miles of dough. My favorite picture, which I didn’t have time to photograph but snapped in my mind’s eye, is of the women in my family sitting at my kitchen table, each with a bowl of sliced peaches in front of her, a knife in her hand, and peach juice dripping off her elbows.

We made and froze 14 peach pies that afternoon. My freezer was filled with pies that lasted all Winter and beyond. We laughed that this should be a family tradition every Summer: loads of peach pies and four generations of women with sticky elbows.

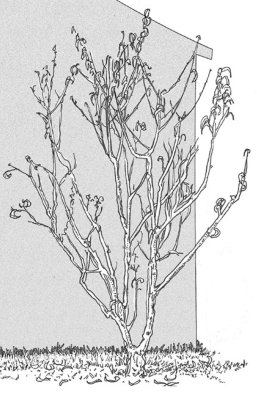

The tree, however, knew something that we didn’t. It had put all its energy into producing fruit and seed for its next generation. The next Spring the tree had few blooms and small leaves. I called our local tree doctor

“Borers,” he said, after one glance. He showed me the evidence, not noticeable to the untrained eye. A tiny hole at the base of the trunk was the only outwardly visible sign of what was occurring inside the tree. A tiny wormlike fruit borer had made its way into the base of the trunk. This silent killer reproduced and spread, not attacking the peaches but voraciously feeding off the inner bark—the lifeblood of the tree—until eventually its offspring killed our peach tree.

We had to cut down the tree: nothing could be done about the borer by the time its insidious presence was obvious. Our valiant peach had done its best to create future generations of trees. And the hundreds of rosy spheres spawned in one Summer? They created hours of family fun, months of delicious enjoyment, years of memories—and a nagging curiosity about what trees know. ❖

By Barbara Kodner, published originally in 2022, in GreenPrints Issue #130. Illustrated by Russell Thornton

What do you think? Do you have an experience with a plant or tree that made you rethink how they might interact with their world? I’d love to read about them in the comments.