Call me a sucker for a good romance, but I feel like I come across a good garden love story almost every day. Whether it’s falling in love with that first tulip of the spring or love that grows between couples as they tend their gardens together. My first garden love is probably an heirloom tomato, but in truth, there are lots of things I love about my garden.

Sometimes, though, love can sneak up on us unexpectedly. That’s what happened to Carolyn Curtis in today’s story, Giants Passing. The giants, in this case, are California Redwood trees. While it’s not unusual to love a tree, she and her husband Don were “ambivalent” about three redwoods spanning the space between their home and their neighbors.

“As deep shade claimed that entire side of our house, we installed skylights over the kitchen sink and the bathroom,” she writes. So when new neighbors moved in and decided to remove the trees (after all, how many giant redwood trees can you have on a 6,000 square foot suburban lot?), Carolyn was looking forward to the change, not to mention some sunshine!

But life has a funny way of surprising us. Gardens especially can teach us things when we least expect it. In Carolyn’s case, there were a lot of surprises that didn’t appear until the trees were gone.

I love this story. It brought a smile to my face and gave me a newfound appreciation for garden love stories.

Enjoy More Stories About Gardening and Garden Love Stories

This story comes from our archive that spans over 30 years and includes more than 130 magazine issues of GreenPrints. I love pieces like these that stand as reminders of how much a garden can mean beyond some favorite vegetables or colorful flowers. I hope you enjoy it, as well.

Giants Passing

Three 95-foot-tall redwoods in the yard: gone.

By Carolyn Curtis

Redwoods: they’re the state tree of California and the whole world knows it. However, not many people, even Californians, live within a few feet of one. For 26 years I lived 15 feet away from three of them, here in our quiet Northern California suburb.

Our next-door neighbors, Lois and Randy, planted them when their children were born, a tree for each one, right along the 6-foot fence they shared with their neighbor Don. After I moved in with Don in the 1990s, we four became very good friends—in and out of each other’s houses, getting season theater tickets together, and chatting whenever we ran into each other by our driveways.

Don and I were ambivalent about the redwoods, with their ever-increasing height and girth and the impenetrable web of their roots on our side of the fence. But we accommodated them, partly out of inertia, but mostly out of love for Lois and Randy. Never a word of complaint about the trees, even just to each other.

We made the most of them: we had a borrowed redwood garden! I tried to grow a bank of ferns against the fence. We set up seating and a table there to enjoy our preprandial wine on warm Summer evenings; it was always ten degrees cooler under the redwoods. In December I’d cut low-hanging branches for holiday wreaths and swags. As deep shade claimed that entire side of our house, we installed skylights over the kitchen sink and the bathroom.

No question: redwoods are kings. Emperors. As the official state tree, the “redwood” is actually two trees that grow only in California: the fast-growing, commercially invaluable coast redwood and the giant sequoia of the Sierras, which is among the oldest and largest organisms in the world. Both species famously live through wildfires. In their upper branches, old-growth redwoods and sequoias support whole ecosystems that researchers never dreamed of until recently.

There is a natural height limit for trees, based on how water travels through a tree’s cells. A tree’s leaves transpire constantly, thus drawing water up from the ground via capillary action, through a layer of cells (xylem) just under the bark, in columns stretching the full length of the tree. Water molecules are attracted to each other (we know this as surface tension) so that if a tube is narrow enough, this attraction overcomes gravity—up to a point. At a certain height in even the narrowest of tubes, bubbles break the surface tension, inhibiting capillary action. Many factors affect the point at which this happens, but under ideal conditions it’s a long way up. Coastal redwoods, at around 380 feet the world’s tallest trees, have figured this out.

Impressive, that alone. But do trees that can attain several hundred feet belong on 6,000-square foot lots in the middle of a suburb, where in a generation they can shade entire neighborhoods? An unspoken question, it grew with the trees.

Then came a couple of big changes. Don died quite suddenly in midsummer of 2017. A couple of years later, Lois and Randy sold their house and moved into a retirement community on the other side of town.

The new owners are Ed and Kim, an easy-going young couple who work in tech, with a 4-year-old boy and a baby daughter. Despite our age differences, we have a lot in common. They appreciate the hot Peruvian peppers I grow and the occasional blooming pot of fragrant bulbs; they share their baked goodies and even brought over a bounteous Thanksgiving plate for me.

A couple of months after moving in, Kim told me that they planned to remove all three redwoods. At least one tree was leaning, threatening their house (and ours, actually). I responded, “They’re your trees. Either way is fine with me.” And I really meant it. After all, I’d lived with them over 20 years. I well knew their minuses and pluses.

Around 8 a.m. in the morning of the fateful day, a jolly crew arrived. One of them got harnessed like a rock climber and shimmied right up one of the trees, chainsaw in hand. Singing lustily in Spanish the whole time, he’d cut thick branches, rope them up, and lower them to his coworkers on the ground, who conveyed them to the chipper parked out front. By the end of that day, the trees were naked spires.

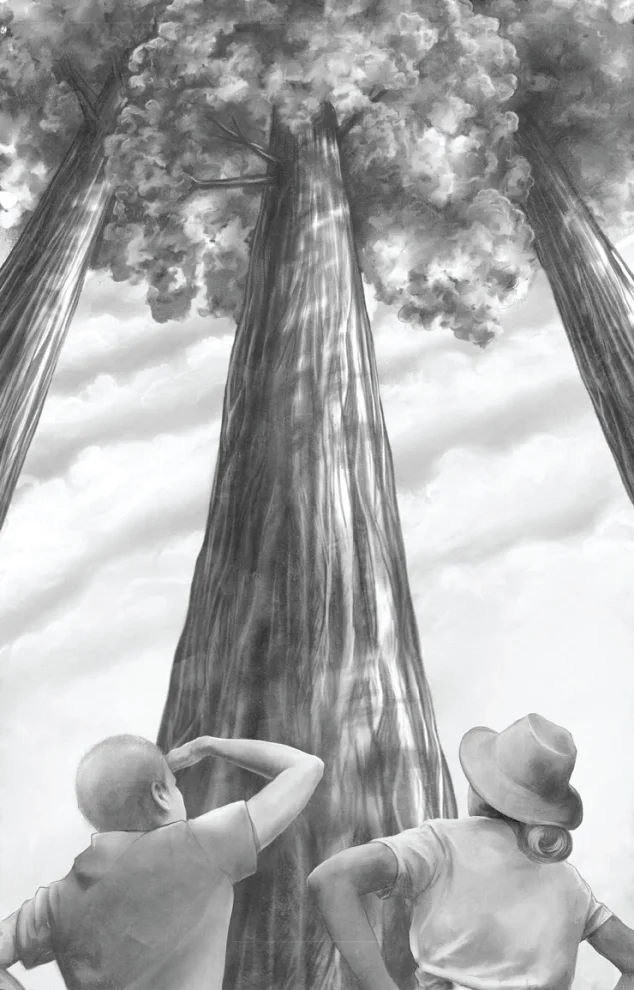

Just before the crew arrived that morning, I had hurriedly taken pictures. I wanted to document our life with these trees, aiming the camera up into them from the patio they shaded, getting them full-size from across the street, showing their upper expanses from the other side of our house.

When I downloaded these pictures to my computer that evening, I couldn’t look at them. In the intervening week before the bare trunks would be sawn down, I could not look at the bereft spires themselves. A crew member told me they were 95 feet tall, not 50, as we’d thought. All that biomass, soon to be gone.

Plants in our backyard were reveling in all the new sunlight. But I was thrown into gloom, unexpectedly mourning those almost mythical creatures, dismembered, their limbs ground to bits.

Then the same jolly crew arrived, with a gigantic crane they parked in front of our neighbors’ house and an open gondola-type trailer truck in front of ours. They cut lengths of the trunks, which the crane picked up and wafted through the air into the gondola. A week after that came stump-grinding day. The largest stumps were 6 feet across at ground level—I think, because, again, I couldn’t look.

I hadn’t expected all this to affect me as much as it did. How much was sorrow over the slaughter of these iconic trees? How much was bound up with the loss of my old life with Don, the old-married-couple convivial relaxation in their shade on Summer evenings? And how much was symbolic of the loss of our fine friendship across the fence, that whole verdant way of life we had, as Lois called it?

In his retirement, Don had become a dedicated native plant advocate, and so was I. We had both worked on preserving wild habitat nearby. Our entire front yard and half the back is filled with native wildflowers and blooming shrubs, around 100 kinds. But trees that attain 95 feet in 50 years, however emblematically native they might be, do not work on a 6,000-square foot lot in the middle of a suburb. I kept repeating this to myself.

The new redwoodless life meant—bang, smash—higher temperatures in our uninsulated house, thanks to the morning sun that the redwoods had blocked all those years. Especially during the heat wave that coincided with the redwoods’ removal. As soon as the sun was over the housetops, it blasted through the windows and the kitchen door’s full-length window and thundered in through the 2- and 4-foot-square skylights in our roof. The first weeks of this were a mad scramble to install blackout curtains, get a better fan, and, above all, bring in the 7-foot ladder and block off the skylights from inside. Somehow the house and I survived the Summer.

The second biggest change, which Don and I had wistfully fantasized about for years, was what to do with the 25-foot by 8-foot plot along the shared fence, formerly deep shade with redwood duff and a few ferns, that was now in full sun most of the day. Answer: at one end, five different dwarf citrus (an orchard!). At the other end, to block the sun slamming into the house in the morning (Don and I never envisioned this), I planted blueblossom, a fast-growing, drought-tolerant, locally native shrub with foamy clusters of pale blue flowers in Spring. This shrub grows to eight feet in its first year (it had better) and gets to 25 by 25 feet at full strength. I planted it so that its morning shade in Summer is aimed right at our mostly-window kitchen door. Fingers crossed.

So: no more living under giant awe-inspiring iconic trees. But among changes in the past several years, this is pretty minor. As always, the garden, ever-changing, ever-fulfilling, helps. Let’s see how the citrus trees bear, and if the blueblossom fulfills its role. And most of all, how the friendship unfolds between the young family on the other side of the fence and me.

I wish they could have known Don. ❖

By Carolyn Curtis, published originally in 2021, in GreenPrints Issue #127. Illustrated by Christina Hess

Do you have any garden love stories that surprised you?