The secret meaning of flowers conjures the idea that flowers are much more than meets the eye—or the nose. I suppose, if you wanted, you could delve into what flowers mean to life on earth, since they are the beginning point of our food chain. You could imagine flowers as a secret code, with spies, covert missions to far-off lands, and undercover agents placing a vase of hydrangeas or dahlias or peonies on a hotel lobby desk to signal different messages.

For many of us, though, the secret meaning of flowers is both deeply personal and also historical. Different flowers are associated with culturally important moments and events. Think of the rose as a symbol of love or the daisy as a symbol of joy and happiness. Flowers may also have associations that don’t relate to their traditional symbolism. The sight or smell of these flowers bring memories to the fore. They transport us to a place that we can’t go to on our own.

For Alison Townsend, it’s the lilac that holds these many memories and associations. In her story, A Sprig of Lilac, she shares her own appreciation of the lilac and what the flower means to her personally. She also takes us through the history of the lilac, from its origin in Persia to the first lilac in Scotland to the lilac’s association with mourning.

Discover the Secret Meaning of Flowers and More Stories About the Personal Side of Gardening

This story comes from our archive that spans over 30 years and includes more than 130 magazine issues of GreenPrints. I love pieces like these that teach me some interesting facts, but also bring those facts to life and make them relevant for my daily trip to the garden. I hope you enjoy this story as well.

A Sprig of Lilac

A flower, of love, mourning, and more.

By Alison Townsend

It’s May, the month of my birth, the heart of what I think of as the season of tender green, before Summer’s heat strips it all away and makes going outside a torture. In my Wisconsin backyard, ferns unfurl their frilly chartreuse fans, mayapples open their satiny parasols, and the Virginia bluebells are a pool of ethereal blue, floating in the kidney-shaped shade garden on the north side of the house. It’s the time of year when you can still see each plant clearly, as if the world is being newly etched, with a bright green pencil, right before your eyes. Sometimes I sit completely still, crouched before a flowerbed, with my hands in the dark earth, lost in that state of awe that is the gardener’s form of meditation, breathing in unison with green and growing things. When I inhale, I smell the heady, intoxicating fragrance of lilacs: the signature scent of Spring.

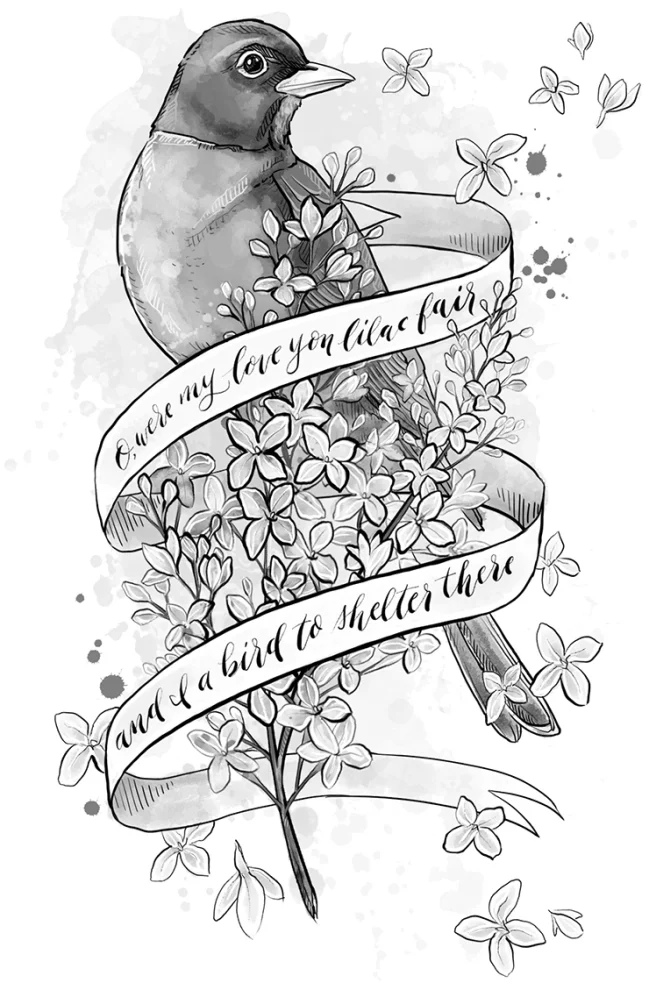

This year, the bush we planted 12 years ago, on my 50th birthday, is finally blooming well, having been moved to the sunnier spot it needed. Every other day my husband picks a small bunch of lilac blossoms and places them in a vase in our bedroom, that they may waft over us as we sleep, wrapping us in their sweet scent. It is an incurably romantic gesture, and I love my husband—who, like many men, is sometimes awkward and bumbling, irritating me with his sheer male-ness—for doing it. Each time I pass the lilacs, I smile. For while they are an innocent flower (historically symbolic of that quality), they are also erotic. The blue stars in our bedroom spill a scent as charged as the moment when, during our early courtship, my husband laid his palm lightly on my ass one Spring night while kissing me goodbye, dizzying me with his touch as I leaned into him. He does not know that lilacs summon this memory, a secret sensation of a time already lost to us in the din and feint of marriage. I must remember to tell him, though he may already know, those bouquets of lilacs an unspoken language between us, filled with the kind of yearning Robert Burns describes when he writes, “O, were my love yon lilac fair…[a]nd I a bird to shelter there.”

Lilacs have been with me as long as I’ve been alive, the white and purple lilac bushes that grew at my parents’ colonial-era house, Wild Run Farm, inextricably wrapped up with my beginnings. It’s even possible, given the time of year I was born, that someone brought my mother a bunch of lilacs in the hospital, as she recovered from the difficult, high-forceps delivery of me, her first child and eldest daughter. When I was growing up, she used to place a huge china bowl of purple lilacs on the back of our Cunningham upright piano. I’d be enveloped in the scent as I practiced, an occasional blue star falling on the piano keys like a harbinger of later Summer, when we’d lie on our backs in the hayfield, watching falling stars streak through the night sky like dreams one barely remembers. Playing outside each Spring, I’d pluck individual stars from the panicles of lilacs to make tiny bouquets in fairy houses I built beneath the roots of the big maple in the back yard. The heart-shaped leaves served as coverlets on tiny beds of moss, where I could imagine myself sleeping.

Lilacs were, I have read, brought to this country by the Puritans, an act which seems oddly at variance with their strict faith. Perhaps the Puritans, and the women especially, needed to plunge their faces into bouquets of lilacs like the ones that I, their distant daughter, brought to school for my teachers, wrapped in wet paper towels, then crimped tight in tin foil cones. Maybe the heady scent of lilacs afforded some relief from the thought of being “sinners in the hands of an angry God,” on a dangerous errand into the wilderness. I imagine that Hester Prynne of The Scarlet Letter, one of my favorite heroines in American literature, must have loved them.

The Latin name for lilacs is Syringa, from syrinx, meaning pipe or flute. Syrinx was a nymph who turned herself into a woody stem to hide from Pan, thus becoming the first flute, a legend I find both charming and disturbing. Their pith can, in fact, be hollowed out easily to make pipes and flutes. It’s said that white lilacs (which have always seemed pure in an almost otherworldly way) are symbolic of youthful innocence, while the purple ones represent first love. Reading even deeper in lilac lore, I discover that a young woman was turned into a white lilac in a churchyard in Wye in Hartfordshire, England, after being “ruined” by a nobleman. Is every lilac really a woman running away from something, captured in her purest form?

Lilacs bloomed abundantly where I grew up in the rural Northeast. Every house had them and it wasn’t uncommon to run across them even deep in the woods, still blooming beside an old foundation or near an old stone wall. Years after leaving Wild Run Farm, my family lived in another Colonial-era house that was shielded from the dirt road we lived on by a 12-foot-high wall of lilacs so thick they formed an impenetrable hedge, bent heavy with lavender flowers. My sister and I slept downstairs, in a room that had formerly been a side parlor. On Spring nights we’d open the unscreened window and let the scent of lilacs wash over us like an invisible cloud, soothing the anxious sleep of our adolescence. When I think of those nights infused by lilac, I want to weep, recalling moments when we lay down our guard against one another and whispered together before falling asleep. Lilacs can live hundreds of years, so they are probably still blooming before that house. Perhaps they were even planted in 1753, when the house was built. Maybe they scented the sleep of other young women who lived there before us, including the ghost of a girl I saw once, dressed in a lilac-colored ball gown, as I stood at the threshold into the oldest part of the house.

As a gardener, I know lilacs grow everywhere in the world. They originated in Persia, where their name is the same as the word for “flower.” The first lilac in Scotland is said to have sprung up in a beautiful woman’s garden from seeds dropped by a falcon. There are as many lilacs in the world as there are Smiths, their names alone an evocative litany—Maiden Blush, Pocahontas, Tinkerbelle. French lilacs are mythically famous. Once, during a difficult season, when I lived briefly and unhappily in South Texas, I took to ordering lilacs flown in from France each spring by an expensive florist. There were none to be had in Texas, for lilacs need cold to survive. It was an extravagant gesture, for lilacs don’t last long when picked, several days at best, despite strategies about crushing the stems and adding sugar or aspirin to the water. But when I buried my face in the clusters of blooms, comforted by the scent of Spring, it was worth it.

Despite the fact that they live in so many places—there is an especially fragrant, low-growing variety named “Miss Kim” from Korea, for example, that conceals the liquid propane tank in my back yard—lilacs seem to me a quintessentially North American shrub. Perhaps this is because of Walt Whitman’s heartbreaking elegy for Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” The title alone is enough to reduce me to tears. In the poem, our great poet-bard mourns the death of the great leader with the return of lilacs in the Spring. The thrush carols its song of death. The coffin travels the nation to its place of rest. And the western star sails the sky till it drops in the night and is gone, like the blue stars that fell on my finger while practicing the piano.

Whitman’s elegy makes sense, for lilacs are associated with mourning. During Whitman’s lifetime, lilac was the color one donned after wearing black for a year, while replacing black-bordered, mourning stationery with sheets edged in lilac. Considered this way, lilac also signifies a return to life after a season of grief. This is, I think, part of what lilacs suggest to us, summoning our own pasts, both personal and national, and a sense of the future, of things beginning again. I cannot imagine living in a world without them, their blue flowerets illuminating the blue of Spring evenings, each star one among many. “I give you my sprig of lilac,” Whitman wrote at the end of his majestic poem. This morning, these words are mine. ❖

By Alison Townsend, published originally in 2020, in GreenPrints Issue #121. Illustrated by Chelsea Peters

Do you have any flowers that fill you with memories?

How do I get this book if there is one.

Where can I get the book?

This article was originally published is issue 121. It is only available (to premium subscribers) as a digital product. Here is a link to the full issue.

https://foodgardening.mequoda.com/toc/greenprints-magazine-spring-2020/#