I don’t often have cats in my garden. I’m out there a lot, so there isn’t a lot of time when a cat might come and set up a nest from which to hunt or prowl. On the rare occasion that a cat shows up, I usually shoo them away. We get a lot of beautiful birds and butterflies around the garden, and the last thing I want is to wake up to Goldfinch feathers scattered across the basil.

However, after reading Cats. Gophers. Sweet Peas. by Terilynn Mitchell, I’m rethinking my approach the next time I have cats in my garden. As you can imagine from the title, this is a story about what happens when cats and gophers get mixed up in the garden. However, it’s not what you’re thinking.

Yes, the cats do chase a gopher. And yes, there is a plenty of hilarity. But you really need to read the story. Consider it a tale of warning. Or perhaps it’s just here to entertain. Or maybe both. Whatever the case, I promise you won’t feel the same about your approach to various wildlife appearing in your garden. Give yourself five minutes to read this and enjoy a few moments of fun and laughter. It’s really a great way to take a break during your day.

Enjoy More Stories About Cats In My Garden, Dogs In Your Garden, and Animals of All Kinds. It’s All In GreenPrints.

This story comes from our archive that spans over 30 years, and includes more than 130 magazine issues of GreenPrints. Pieces like these that turn gardening stories into everyday life lessons always brighten up my day, and I hope this story does for you as well. Enjoy!

Cats. Gophers. Sweet Peas

A problem of boundaries.

By Terilynn Mitchell

When I first moved to my new home in Northern California, the yard was an overgrown, disheveled mess. Weeds sprawled over the landscape like unwelcome squatters. I proceeded to work the land like a small-scale clear-cutter. I didn’t have a clue what I was doing, but I did it with conviction.

Once I had the horticultural wildlife under control, I spent two weekends weeding, cultivating, and fertilizing the ground in a particularly barren area. When that was done, I soaked some sweet peas overnight before pushing them into the earth the following day. To add a splash of color, I also broadcast a variety of native wildflower seeds.

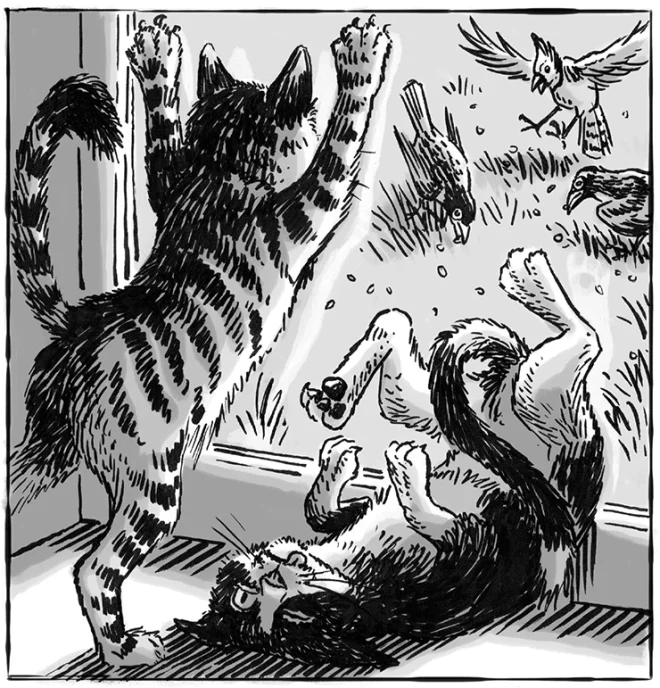

For the next three mornings, Mica and Miss Skeeter, my indoor cats, nearly gave themselves concussions hurling them-selves headlong into the windows. My housebound hunters were trying to get the fat birds that feasted on the seed I’d scattered on the soil. My potential splash of color became a novel food source to the jays and robins, who themselves looked like novel food sources to my frustrated kitties.

Since the sweet peas were planted more deeply, they alone escaped the birds. Eventually they grew into vines as long as three feet. I had sown them along a wire and lattice fence, but they didn’t seem at all inclined to trail up the fence on their own. So on a morning in late May, I decided to go out and teach them proper plant etiquette. It was 10:00 a.m., and the sun was already turning up the heat. I carefully started threading tendrils of vines in and out of the fencing. This delicate operation evolved into mindless labor. Still, I welcomed the change from the hypervigilance required at my job as a veterinary technician. I entered a trance-like state, at one with nature.

Suddenly I got that prickly feeling I was being watched. I turned my head and found I was being studied—by a young gopher! I didn’t know how long she’d been scrutinizing me. I also didn’t think it was normal for an adolescent gopher to sit above ground staring at a human on the other side of a sweet pea fence. She had an essence of youthful sweetness and curiosity, but I spun into what I call Clinician Mode. I studied her face and body through the lattice as best I could—no signs of injuries, smooth coat, good weight, and normal breathing. Maybe she was otherwise challenged, but I frankly don’t know how to recognize a weak-witted gopher.

“What are you doing?” I finally yelled at her. “Get back in your hole, you fool! The cats are out.”

She studied me for a moment. Oh dear, I thought, she is slow. Or maybe the sight of a large mammal talking in a foreign tongue and waving its arms amused her. She finally turned around and lumbered back to her burrow a foot away. Satisfied, I finished my yard work and got out of the sun by noon.

As fate would have it, two hours later, Miss Skeeter flew over the trellis fence with an adolescent gopher in her mouth. My agile feline predator got her start in life as a feral and unweaned kitten, found in a parking lot in the rain in Los Angeles. Covered in mud and oil, she had presented with a broken pelvis. Now two years old, she was my strongest cat, determined to scratch and claw her way out of the windows and appoint herself the best hunter in Sonoma County.

Skeeter dropped the rodent, ready to play with her catch. “Told you so,” I muttered angrily at the hapless critter as I hastened toward them.

To my surprise, the gopher had not only survived, but looked intact. I felt sure it was the same one that had been watching me hours earlier. I cautiously scooted her away from the cat and watched her totter into a thicket of fleabane. I used a long stick. I’d been shown the year before, by a dental imprint in my garden clog, that such creatures rarely appreciated my intervention.

Against my better judgment, and clueless to the gopher’s actual gender, I found myself wanting to call “her” something. Giving a name to a feral creature signified an unhealthy attachment and hinted at impractical ownership. But while the voices of wildlife experts warn us not to feed the wild animals, no one says you can’t name them. So I dubbed her Waddles.

I guess I have lousy boundaries.

Reluctantly, I walked away. Nature happens, I firmly told myself. Sometimes it requires you leave well enough alone and let it follow its karmic design.

Besides, the vacuuming and laundry weren’t going to get done by themselves. When one houses special-needs cats, it becomes imperative to stay a step ahead of the Health Department. Dang if Waddles’s screams minutes later didn’t bring me rushing outside again. By now Mica had joined Miss Skeeter in tormenting this poor animal. Five-year-old Mica had a neurological disorder, rendering her incapable of hunting her way out of a paper bag. But she’ll happily assist in torturing any prisoners of war.

I hissed the cats away and checked Waddles out as best I could. Amazingly, she’d still escaped trauma. I grabbed a twig and prodded her into a thicker area of unruly fleabane while I lamely scolded my carnivorous kitties. They certainly weren’t hungry. I resumed my housework, but felt compelled to check the yard every ten or fifteen minutes. Miss Skeeter and Mica went back to huddle over the fleabane patch, but I noticed that occasionally they sprang away. A pattern developed to their hovering and jumping back. Finally, my own curiosity got the better of me.

I returned outside to reassess the situation. By now it was about 4:00 p.m., the temperature had spiked into the 90s, and the sun beat down with a vengeance. My two elderly cats were fixated on a hole in the ground.

Waddles, bless her little heart, had started digging a new gopher hole. Every time she threw dirt out, she spooked the cats and they jumped back. She busied herself doing what she knew best, and I admired her simple wisdom.

The sun shone directly into her narrow cavern, which went about ten inches into the ground. She’s young, I thought, and undoubtedly tired. It had been a long, stressful afternoon, and adolescent animals don’t have the same reserves as an adult. Young animals dehydrate quickly and are more vulnerable to hypoglycemia. I needed to do something.

Oh here I go again. Why can’t I just leave things alone? I found myself grappling to think of some kind of practical supportive measure when I remembered the honeydew melon in my refrigerator. Water and glucose! What a flash of genius! I tried to stem my swelling pride. All the caveats of the wildlife experts escaped me at this point.

I rummaged through a kitchen drawer and found my melon baller way in the back. I dug the baller out, and then spent five minutes fitting everything else back into the drawer so I could close it. Since Waddles was small, I employed the smaller end and carved out some little honeydew rounds for her. I gently dropped them into her new hole. As she immediately began munching into one of them, I smugly imagined a note of gratitude.

I herded the cats in and called it a day. I had my own to care for, after all, and certainly couldn’t take on the rest of the world. I do try to accept responsibility for whoever falls prey to one of my brood. In fact, I had become something of a frequent flier at the Wildlife Rescue office, each time offering another orphan and a $20 bill to assuage my guilt. Still, I hoped for the best for Waddles.

I was in the business of saving animals. An uncomfortable contradiction existed, considering I only took in cats at my own small sanctuary. Cats are obligate carnivores, with sharp predatory skills. They need meat, since this is the only food their digestive tracts can utilize. Nonetheless, I grounded my four-legged roommates for the evening and fed them a civilized dinner.

The consequences of my soft-hearted dearth of boundaries became crystal clear within the week. Waddles told two friends, and they told two friends and so on and so on … Almost overnight, my garden transformed into a moonscape with large craters—from fresh gopher holes.

All of my sweet peas died. ❖

By Terilynn Mitchell, published originally in 2020, in GreenPrints Issue #121. Illustrated by Jeff Crosby

Have you had times when you’ve kicked the wrong animal out of your garden? I’d love to read your story in the comments.