In the 1920s, many newspapers and magazines featured glowing accounts of a man who transformed a desolate, barren, and depressing site into one of the country’s most fabulous gardens. Visitors flocked by the thousands to see his flowers—geraniums, snapdragons, phlox, asters, roses, and more. They came to see his trees, shrubs, lush turf, fountain, and large birdhouse. So impressive were his gardens that the New York Times commended the man for adorning “the gruesome place with flowers, trees and shrubs, and the yard, which five years ago was desolate and littered with stones and rubbish, is now a thing of beauty. The rose garden is an inspiration to dark and troubled souls.”

What made those gardens so impressive and moving was the fact that they were located on the grounds of New York State’s infamous Sing Sing Prison. And the creative gardener was Charles Chapin, a convicted murderer. Adding more drama was the fact that Chapin had been one of the nation’s most prominent newspaper editors. In fact, at the time of his crime, he was editor of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York Evening World.

The story of Charles Chapin—who would become known as the “Flower Man of Sing Sing”—began in September 1918 when his own newspaper published an extra edition with this headline: CHARLES CHAPIN WANTED FOR MURDER! His wife was found shot to death in a hotel room and Chapin had left a note behind admitting he killed her. Most New Yorkers knew that Chapin was editor of that newspaper, so copies quickly sold out.

Shortly after, Chapin turned himself in to the police. He claimed it was a mercy killing, that he could not leave his wife financially destitute. For some time, he had been lavishly out-spending his considerable income. When he became editor of the World, Chapin and his wife, Nellie, lived in one of the city’s most expensive and exclusive hotels, the Hotel Plaza on Central Park. He had a maid, daily barbering, and exquisitely tailored suits with gilded watch fobs. In addition, he possessed a yacht, a touring car, and horses. The couple frequently took extravagant European vacations. The burden of those expenses, along with stock market losses, pushed Chapin into formulating a murder-suicide plan.

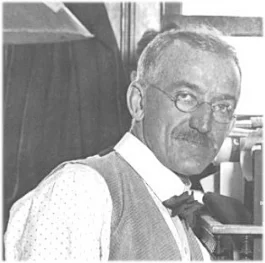

Charles Chapin in the City Room of the New York World

Checking into another New York hotel for the weekend, Chapin waited until his wife was asleep before he pulled the trigger. He then wrote and mailed a farewell letter to the World saying, “When you get this I will be dead. My wife has been such a good pal. I cannot leave her alone in the world.” However, he couldn’t end his life. Instead, he rode a series of taxicabs all over New York City. Sometime during those rides, he saw the headline in his own newspaper announcing he was wanted for murder. That prompted Chapin to turn himself in to the police. He admitted his crime and signed a confession. When he appeared in court, Chapin pled guilty to murder in the second degree, a plea that spared him the death penalty.

In January 1919, a judge sentenced the 60-year-old editor to 20 years in New York State’s Sing Sing prison. The impact of his crime and the reality of prison life took a toll on Chapin. Before long, he was in the prison hospital—frail, weakened, deeply depressed, and on the edge of death. There he was visited by Sing Sing’s new and progressive warden, Lewis Lawes. Sensing that Chapin’s health problems had more emotional than physical causes, Lawes initiated a cure for Chapin’s depression by asking him to become editor of the prison newspaper, the Sing Sing Bulletin. Chapin agreed. His health and spirit were quickly restored. As editor, he wrote most of the material under various pen names.

In the fall of 1923, Chapin approached Warden Lawes on the prison grounds. Pointing toward a desolate plot of land where stones, sand, and piles of old bricks had been dumped, Chapin asked for permission to build a small garden. Lawes gave his approval but said he had no money in his budget for the project. However, he would provide Chapin with prison labor. Chapin’s spirits soared, and he said, “That’s fine, Warden. I’ll make roses grow in that desert. Wait and see.”

Chapin knew nothing about gardening, but, a news reporter, he knew how to gather information. He got a friend to send him basic instructions along with eight volumes of the work of famed botanist Luther Burbank. Chapin spent the winter carefully and methodically studying those books. Then he began writing letters to garden magazines, nurseries, and fertilizer manufacturers asking for donations. Impressed by letters postmarked from Sing Sing prison, they gave him an enthusiastic response. The American Rose Society sent thousands of rosebushes. Nurseries sent irises, peonies, hyacinths, daffodils, crocuses, and petunias. When he was unable to get tulips, Chapin turned to the prison chaplain and asked him to “pray for tulips.” The following day a bulb importer on Long Island wrote Chapin saying he was sending the prison 500 tulip bulbs. Thousands more soon arrived, so much so that Chapin pleaded with the chaplain to stop praying for tulips Sing Sing Prison and instead pray for Madonna lilies. Those also began arriving.

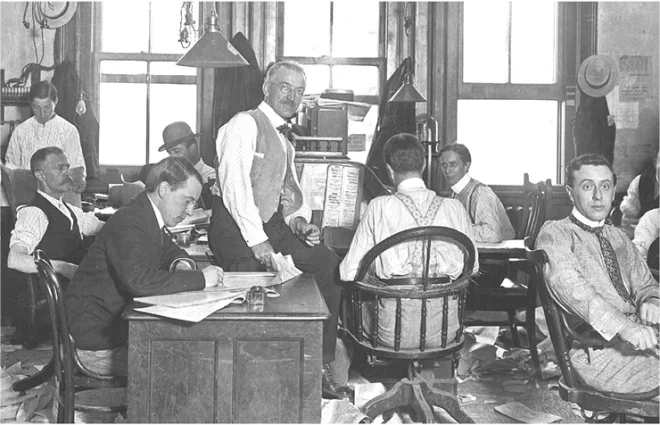

Sing Sing Prison

Row by row and field by field, Chapin, with labor from other prisoners, began to transform the drab prison grounds into a place of color. One plot of land contained thousands of rose bushes. He planted a long row of blue spruce seedlings. In the center of a ten-foot-square lawn, Chapin added a water fountain. Chapin’s men cleaned and cleared a former garbage dump—and turned it into a field of blazing tulips. By the mid 1920s, birds in large numbers were attracted to the gardens, so Chapin began making plans to add two huge birdhouses.

Chapin designed his gardens to be sensitive to the needs of inmates. He carefully arranged one section so that the final viewing prisoners would see as they walked toward death row was a colorful border of flowers. He favored blossoms that were deep red, the “color of life,” Chapin explained. Around the death house, Chapin planted lilacs to perfume the last days of condemned prisoners.

Not only did the gardens transform the prison grounds, but the gardening also reshaped Chapin’s personality. In the news business he had been a hard, driven boss who was feared and loathed by his reporters. Shortly after his arrival at Sing Sing, Warden Lawes received this letter from an employee: “I knew Mr. Chapin…in the years he was at the World. That is, I knew intimately the anguished stories of the hundreds of writers whose lives he made a living hell. I used to think him a sort of devil sitting on enthroned power in the World office…If you enjoy him, I hope you keep him long and carefully.”

Chapin was utterly changed by his meticulous attention to gardening. He moved from being constantly impatient and unkind and evolved into a gentler and more compassionate human being. Chapin himself appreciated this evolution. Writing to Constance Nelson, a young woman with whom he was romantically linked via correspondence, he asked her, “Do you think that growing flowers did it?”

For his efforts, there was nothing but appreciation and praise from guards as well as the prisoners. In fact, one of Chapin’s editors visited Sing Sing to interview his former boss and asked how Chapin managed to protect his gardens. Chapin was confused. “Protect them from what?” he asked. “From being trampled or destroyed by prisoners,” said the editor. That concept was utterly foreign to Chapin. Not once had any prisoner damaged any plants. And when the editor asked if he had guards for his gardens, Chapin pointed out that all 1,200 men locked up at Sing Sing acted as the garden’s guards.

Of his gardening, Chapin wrote to a friend, “It’s the greatest happiness I have found…in prison. I am up at five every morning and am at it almost constantly until it grows too dark to see.”

Chapin died of bronchial pneumonia on December 12, 1930. At his request, he was buried beside his wife, Nellie. For some years after Chapin’s death, his beautiful gardens were carefully tended by another generation of prisoners. ❖

STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP, MANAGEMENT, AND CIRCULATION

(required by 39 USC 3685) for Winter 2015 for GREENPRINTS, published quarterly at 23 Butterrow Cove, P.O. Box 1355, Fairview, NC 28730-9568. having headquarters or general business offices at 23 Butterrow Cove, P.O. Box 1355, Fairview, NC 28730-9568. The names and addresses of publisher, editor, and managing editor are: Pat Stone, GREENPRINTS, 23 Butterrow Cove, P.O. Box 1355, Fairview, NC 28730-9568. GREENPRINTS is published by Robert K. and Rebecca N. Stone, 23 Butterrow Cove, P.O. Box 1355, Fairview, NC 28730-9568. The known bondholders, mortgages, and other security holders owning or holding 1% or more of the total amount of bonds, mortgages, or other securities are: none. The Average number of copies each issue during the preceding twelve months are: (a) Total number of copies printed (net press run), 12,721. (b) Paid Circulation: 1. Mailed outside-county paid subscriptions 11,750. 2. Mailed in-county paid subscriptions 54. 3. Paid distribution outside the mail 0. 4. Paid distribution by other classes of mail 0. (c) Total Paid Circulation, 11,804. (d) Free or Nominal Rate Distribution 1. Outside-county copies on PS Form 3541 113. 2. In-county copies on PS Form 3541 0. 3. Mailed at other classes 137. 4. Outside the mail 126. (e) Total Free or Nominal Rate Distribution 376. (f) Total Distribution 12,180. (g) Copies Not Distributed 541. (h) Total 12,721. Percent Paid 96.9%. Actual number of copies of single issue published nearest to filing date are: (a) Total number of copies printed (net press run), 12,700. (b) Paid Circulation: 1. Mailed outside-county paid subscriptions 11,655. 2. Mailed in-county paid subscriptions 56. 3. Paid distribution outside the mail 0. 4 Paid distribution by other classes of mail 0. (c) Total Paid Circulation, 11,711. (d) Free or Nominal Rate Distribution 1. Outside-county copies on PS Form 3541 110. 2. In-county copies on PS Form 3541 0. 3. Mailed at other classes 106. 4. Outside the mail 98. (e) Total Free or Nominal Rate Distribution 314. (f) Total Distribution 12,025. (g) Copies Not Distributed 675. (h) Total 12,700. Percent Paid 97.4%. I certify that the statements made by me are correct and complete. Pat Stone, Publisher/Co-Owner

Previous

Previous