Those of us who have a garden know that we are fortunate ourselves. As the 17th-century poet Abraham Cowley put it in 1657:

“Who that has reason, and his smell,

Would not among roses and jasmin dwell,

Rather than all his spirits choak

With exhalations of dirt and smoak?”

William Coles, a renowned botanist during Cowley’s time, described a house without a garden as “more like a prison than a house.”

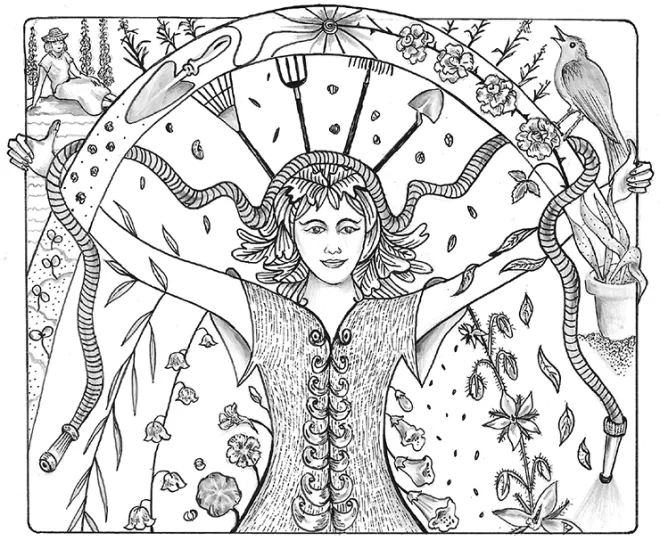

These days we all know about feeling confined, but we lucky gardeners can escape to our gardens. In the past, though, gardens were not only comforting retreats, they were also where healing plants were grown. They were our ancestors’ pharmacies. Abraham Cowley again:

“Nor does this happy place only dispense

Such various pleasures to the sense,

Here health itself does live…

Scarce any plant is growing here

Which against Death some weapon does not bear.”

Many of the old herbals give plant recipes for curing a multitude of ills, including mental ones. In John Gerard’s famous Herball of 1597, we are told that the flowers of borage can be used “for the comforte of the heart, for the driving away of sorrowe, and increasing the joie (joy) of the minde.”

The Doctrine of Signatures believed by the old herbalists compared the attributes and physical appearance of plants with the ailments of the body. A plant, by this reasoning, looked like the part of the body it cured. This was thought to be provided by God as a guide to its use. Thus St. John’s wort, with its perforated leaves and characteristic red color (when steeped in olive oil), should be used to heal cuts. Lily of the valley, with its drooping flowers, could help “drooping of humours in the brain.” We know now that all parts of this heavenly smelling plant are toxic. Indeed, the Doctrine of Signatures was at times dangerously misleading.

Of course, many plants were useful medicinally. Some are still used that way today. Digitalis comes from foxgloves and is still used as heart medicine. In George Elliot’s Silas Marner, Marner gives an old woman foxglove tea, “since the doctor did her no good”—with miraculous results. Foxgloves can be toxic, however, so must be used with care.

Another drug, colchicine, comes from the Autumn crocus and is used to treat gout and leukemia. Willow trees contain salicylic acid, the source of aspirin. A tea made from it helps relieve “ague” or rheumatism. But then, willow tea—and aspirin—can irritate the stomach.

I can vouch for one thing: It’s best not to learn the potential hazards of a plant the hard way. One time I tried to make horseradish sauce from a root I dug up in my Winter garden that I thought was horseradish. I mixed it with sour cream and tasted just a bit. By the time the roast beef was cooked, I was in bed where I stayed the rest of the day vomiting. Another time I attended a party where “fiddlehead ferns” were served. Everyone there spent the night ill.

Gardeners today still grow many of the old-time heal-ing plants—for pleasure. We are looking for a different kind of healing, the healing of beauty. Some of these, like pansies, calendula, lavender, and nasturtiums, are even edible. Roses and rosemary are grown by most of us and have so many uses that Herbalist John Parkinson (1567–1650) wrote, “You might be as well tyred in the reading as I in the writing if I should set down all that might be said of it.” He did, however, mention that these two plants were able to expel “the contagion of the pestilence.” He was writing about the Great Plague of 1665, which killed so many. Seventeenth-century diarist Samuel Pepys wrote about the plague, complaining (although he did not use the term) of the lack of social distancing by “a gaggle of striplings making fair merry and no doubt spreading the plague well about. Not a care had these rogues for the health of their elders.” We have heard the same complaint these days.

But oh, how hard social distancing—and life itself—is if you don’t have a garden. There you can breathe fresh air, sit, dabble in the soil, listen to the birds, and enjoy a wonderful world.

Let us always remember, fellow gardeners, how blessed we are. ❖

Previous

Previous