The sky is that piercing, heart-wrenching, soul-lifting blue found only on a clear Wisconsin Summer day—and walking in the clinic’s parking lot, I am keenly aware of the clarity of the world around us. Just ahead of me, my husband Ed’s parents, Harry and Grace, walk arm-in-arm, while I stay discreetly behind, giving them a little space of their own. We have just been told by the doctor that Grace’s cancer is not operable. Treatment would be devastating and debilitating. With it, she could have a year left—one long, agonizing year. Without it, maybe six months. Her choice has been the latter, to die as naturally as she has lived her 76 years, at home on the family farm, surrounded by fresh air and family.

We walk slowly, waiting for Ed who has stayed after to get some information on hospice care. Surely, Grace intensely experiences the blue sky. I marvel at the straightness of her back, the defiance in her walk. She is chatting away at Harry, who looks dazed. She pats his arm reassuringly: she is comforting him about her tragedy.

Ed catches up with me and takes my hand, squeezing it slightly. I can feel the familiar space where his index finger should be—a digit lost long ago to a corn picker—and the cleft is somehow comforting in its familiarity. Life is full of spaces, some small, some large. Most times, we adapt and move on. But a life is not a finger, its absence not something to which we can simply adjust; two miscarriages taught me that. Although I have been blessed with four healthy children, there has always been a space in my heart for the children I would never know.

Living on a family farm, everyone pitches in for every chore, whether weeding the garden or chasing the cows out of the corn. Yet each member seems to fall into a certain task or, more likely, many tasks that are acknowledged as personal. Grace’s tasks have been to hold us all together, to preserve the garden’s bounty, to care for the flowers, and to nurture the numerous kittens dropped on the highway by callous strangers. She’s been the one who always balanced the farm books and tempted our taste buds with treats like her secret-recipe red velvet cake. That smile of hers is part of our everyday lives, and I wonder now how we will live without it.

As we turn into the long, poplar-lined driveway, I thank God the children are not home, that they still have a little time before we tell them something that will set their lives on a tilt. Kyle, our oldest, is a veterinarian in another town. Jon is finishing up a research project at the university where he studies agribusiness in preparation for someday taking over the farm. The girls—17-year-old Emily and 14-year-old Kelly—are spending the week at theater and bible camp, respectively. I don’t know how we’re going to tell them, but I’m confident they will handle it with the flexibility of youth. Ed is shaky, but he’ll soldier on. When I try to imagine what life will be like for Harry, though, the thought sits like lead in my stomach. When Ed lost his finger, we were still newlyweds. I found myself imagining life without him, and just the thought was unbearable. How will Harry handle the reality of an end to 48 years together?

Ed and I drop off his parents at the farmhouse, then continue the short drive to our own home, set a comfortable distance down the wide driveway. We change for chores; even in the midst of personal upheaval, the animals must be fed and watered, the eggs collected, the cows milked. Ed has to finish baling the hay because the weatherman has predicted rain. Living on a farm makes you aware of life’s requirements every day. Anything else—even dying—has to come second. That certainty and forced practicality is somehow reassuring.

I assume Grace will want to rest, so I’m surprised at her phone call.

“Ann, could you come over for a little while? Just to talk?”

I traverse the wide yard to the big old house as I have done thousands of times as a young bride, then as a mother, to ask advice on a recipe, a pattern, a child’s illness. That house has been part of my life as long as I can remember. Ed’s sister, Emily, was my best friend, and as children we spent hours in the attic, digging through ancient trunks of clothes, playing dress-up, and giggling through many a sleepover. I remember her disgust when I would flirt with Ed and follow him around as he did his chores.

The house also sheltered us in our sorrows. When Emily was killed by a drunk driver our senior year, I sat in the living room with Grace, arms around each other, each comforted by the other’s presence. After each of my miscarriages, Grace and my mother sat on either side of me in that same room, cradling me in a sandwich of compassion. And when my own mother passed, it was Grace who gave me strength. I want to give Grace that support now, but I’m not sure that I am capable of pushing aside my own grief to assuage hers.

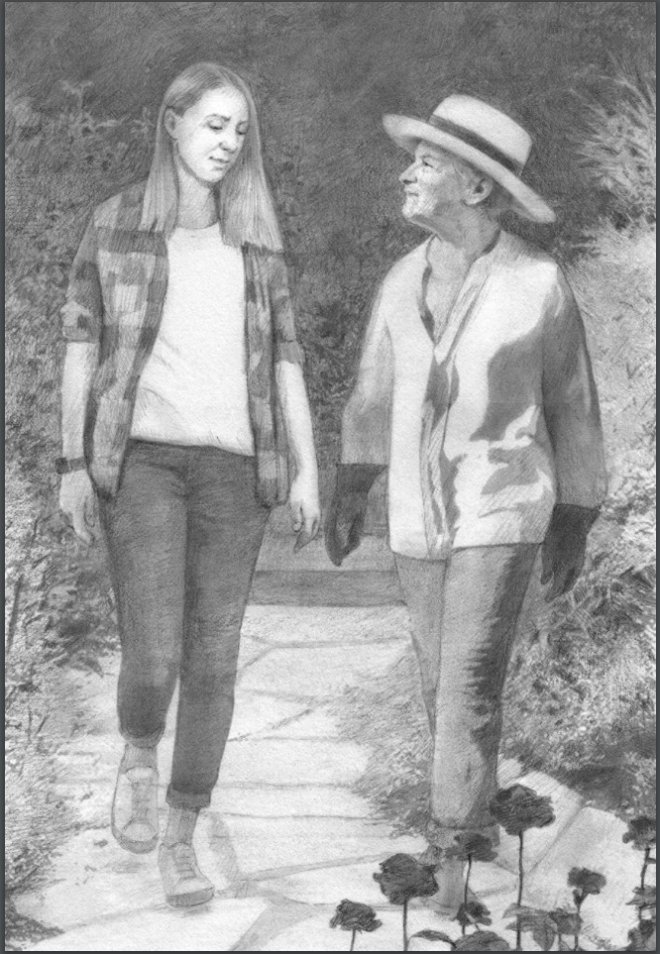

The weathered porch boards squeak, reverberating with echoes of shared secrets and children’s laughter, of loss and anger, of generations of farm women recounting family stories as they stitched quilts or snapped beans. I knock briefly on the door before stepping inside. Grace is waiting for me in the front hall wearing her gardening clothes: a pair of faded jeans, one of Harry’s old loose shirts, fraying sneakers, and a wide-brimmed straw hat. Beneath the hat, her thinning white hair fluffs around her face like spider silk, and the baggy clothes emphasize her fragility.

“Come,” she says, and I follow her through the kitchen to the screened back porch, where she snatches up a pair of gardening gloves and shears from the perfectly organized pegboard.

Beyond the long, white-fenced backyard, the adjacent field shows fresh green corn plants nudging their way skyward. They are still short enough that I can see, in the distance, the one spot where the neat rows are slightly askew, leaving a small space where Ed had veered during planting to avoid disturbing a killdeer nest with speckled eggs mimicking rocks. Ed noticed the mother pretending to have a broken wing to lure danger away. “Couldn’t just run ‘em over,” he grinned when Harry teased him about it. “Ma would’ve killed me.”

Grace and I stroll through the garden, and as always I marvel at the diverse world of color and form that she has created. The garden is divided into various areas, and all seem to be quivering with light and unseen life. There’s the butterfly garden, a riot of varying hues, attracting fire-bright monarchs and soft cabbage moths. A little ways over, a redbud tree drips with the claret of hummingbird feeders, and now and then a moving dart can be seen among the ruby hollyhocks. Taking up fully half the fenced area is the rose garden, Grace’s pride, perfect and symmetrical, with a fieldstone path winding through the meticulously pruned wonders of color and form.

Although for thirty years she has generously shared with me her home, her son, her farm, and her love, the flower gardens have always been Grace’s domain. Under her watchful eye, I helped dig, weed, and transplant—yet all work has been on her order, to her design. I’ve always admired her instinct as well as her knowledge, as she assuredly pruned back the lilac bushes or fearlessly cut through root balls to divide hostas and peonies. I marveled at the way she always knew exactly when and how to powder the rosebushes or clip off the spent blooms to make way for new buds.

Grace used to handle the farm books with the same assurance, but turned them over to me when we put all our records on the computer. She resisted the new technology, claiming that it was beyond her ken, preferring instead to increase the hours in her garden.

“These are the early bloomers,” Grace is saying now as she efficiently snips off a faded blossom. “They pack a lot of color when you need it most, before the rest of the garden comes alive.” We move down the line, and she points out the occasional bush.

“These over here will come next. See, there are nubs already where the blooms will form. I arranged the bushes for unbroken color all season long.”

She moves to a thin, sickly bush that seems somehow out of place amidst the robust plants. She crouches next to the sad little shrub and fingers an anemic bud that will wither before fully flowering.

“This one has been weak from the start. I tried to save it, to make it healthy, but sometimes even my best efforts aren’t enough.” She rises and looks around. “They’re all beautiful,” she continues, “and they all wither and die in their own time. We try to keep them as long as possible, but sometimes there’s a drought, sometimes the weather’s too cool and wet, sometimes an unexpected frost might kill them early. And sometimes, they just simply don’t have the strength to survive. That’s just the way of it.” Her tone is soft, sad, her faded eyes scanning the horizon.

She turns and, wrapping her thin arms around me, finally lets the tears come. I hold her close as we rock together, not speaking. After a while she breaks away, pulls a tissue from her shirt pocket, and wipes her nose, embarrassed at her outburst. She regains her composure and looks me straight in the eye.

“Ann, I want you to teach me to use the computer.”

“Now?” I say without thinking, then cringe at the thoughtlessness of my question. But she doesn’t flinch, just looks beyond her hat brim into the sky where clouds are moving across the previously unbroken blue.

“I guess I just want to bloom once more,” she says. “Will you teach me?”

I nod. I will teach her about the computer—and in exchange, ask her to explain how to prune the bushes and to write down her recipe for red velvet cake. Together we will dig out the sickly rose bush and plant a hardier one that, with love and luck, will blossom right up to frost.

Trying to fill the space. ❖

Previous

Previous