Read by Matilda Longbottom

I worry about my garden in the winter. Most people don’t. Most gardeners find January the one month that they can wrap themselves in a quilt next to the fire, feast on last summer’s strawberry jam, and thumb through the catalogs, imagining their next year’s tomatoes and pumpkins just as shiny and big as the ones in the ads. In their grim way, most midwestern gardeners find the dark, cold month of January joyful. Even though they fight the wind and ice, they have a little more time for their own thoughts, for their hobbies, before the spring, with its frenzy of tilling, planting, and weeding, begins.

During the last five years, the Iowa winters have been mild. The January thaw has now routinely found us playing tennis in light sweaters for at least one day mid-month, and conversations with parents and grandparents overwintering in Florida almost always find their way to jokes about coming on back home to warm up. Yet we in the Midwest are mistrustful of surprises, no matter how seemingly good, and can only view them as bad omens. These mild winters have been indicators of hot, dry summers: drought years that have had these same relatives reminiscing of the Dust Bowl and Depression.

“Last summer, we only got one haying,” my neighbor told me. “Never been that bad since back in ’36. We planted that year, all right, then nothing.”

So this morning I was excited to be standing here at my window, looking out at the drifts circling and swirling, piling higher and higher, the wind howling and billowing the snow into the air. Last night, the evening was crisp and calm. Then about midnight, large dry flakes began falling, covering my front stoop and the cornfields across the road that the pheasants and sheep are still gleaning. I pulled up my comforter and eased into a gentle sleep only to wake at 4:00 a.m. to the hammering wind driving the snow against the window, the glass rattling in the frames, the flakes seeping through the storms. The cacophony, the power of the storm, was too much for me to return to sleep, so I rose and sat in the dark for several hours, watching the blizzard force itself down upon the countryside.

I had had a busy day ahead, but now I enjoyed the thought of a snowbound day at home to do what I wished. I wished to stand at the window and think how good this snow was for the garden, how it was so normal for this time of year, how it provided needed moisture and ground cover.

I grow my crops in a 20 x 40 plot just outside the door of this old, converted one-room country schoolhouse. The building, a white square box built in the 1920’s, sits on top of a hill in the heart of the Amish community near Kalona, Iowa, the largest such settlement west of the Mississippi. During the growing year, I watch from my garden. I see the corn and bean fields unfold in the valley below, the scraggly beard of trees following Dirty Face Creek as it cuts across the landscape, the bright red barns and white farmhouses receding into the horizon.

From my garden at night, I hear the coyotes howl as they slink out of the creek cover and prowl toward the farmsteads. The battery-powered reflectors on the Amish buggies blink on and off in the dark, their horses clip-clopping up the hill, the wheels churning on the gravel, flinging up mud and muck. Sunday night is Amish date night, when buggy after buggy rolls by, the young couples inside driving home from evening services sometimes as late as midnight. Late Sundays, I like to stand out in my garden, trace the constellations in the black sky, and take in the buggy parade, the noise rising to a crescendo as horses approaching my hill break into a gallop. I watch them disappear down the road, the black carriages like shooting stars, their orange slow-vehicle triangles fading from sight.

On Christmas Eve for two years in a row, buggies have pulled into my drive, Amish neighbors arriving with gifts of pickles and relishes from their gardens.

“Merry Christmas,” a young Amish woman said as she appeared on my stoop and handed me a pint-sized Mason jar, a red ribbon looped around its belly, a handwritten label neatly affixed to the lid that read: Strawberry Jam. She stood barelegged in the cold, her feet pushed down in buckle-jangling galoshes, her plain black dress, fastened with straight pins, hitting just below her knees. A purple wool shawl wrapped around her head and shoulders framed her face, skin scrubbed, free of make-up, with a pink hue that reflected years of hard work and a life free from the pressures of normal American culture.

“Merry Christmas, and thank you so much,” I said, worrying that I had nothing to offer her.

My neighbors, Barb and Tom, worried about the same thing. We are some of the few “English” in the area. All three of us admire the Amish and recognize that their religion dictates they shun worldliness. As simply as we ourselves live, as much as we try to preserve and blend in with the spirit of the landscape here, we also know that, with our cars and telephones, we are worldly. Yet because they are freed from competitiveness and striving, because they maintain a real sense of community and live a life I wish I could, I’m drawn to the Amish and feel honored when they include me in gatherings and customs.

Barb, Tom, and I wanted to reciprocate, to share something from our gardens in return, to let our small individual plots become a link to a larger community. So, on a cold but clear New Year’s Day, we loaded up our own Mason jars of preserves, tucked in a few bonus goose and duck eggs, and set out to distribute our gifts. “If we do this every year from now on,” Barb said, “they’ll think that’s our custom.”

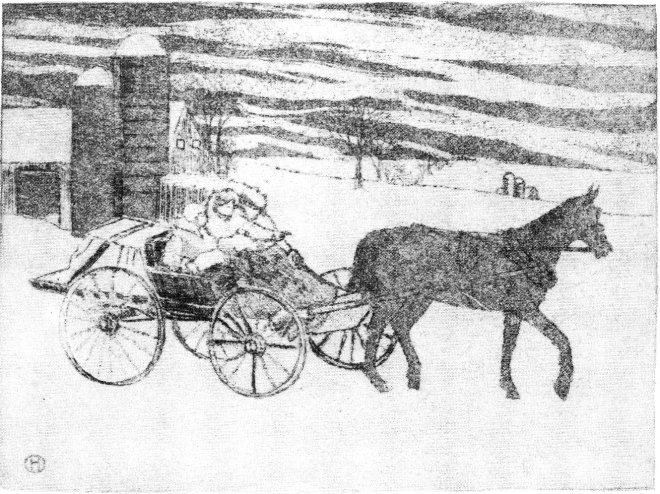

With a bright red bow and harness bells tied on Emily, the horse, we set out to greet the neighbors and bring in the New Year in Barb and Tom’s cart, an old sleeping bag draped across our laps and tucked around our knees. Emily loved the task and had to be held back froma gallop, her mane flopping and fluttering in the wind, the bells beating a steady rhythm as we headed south toward the country store and the extended family who minded it. The horse veered into the store’s lot and hitching post, one of her more usual stops, but Barb snapped the reins and guided her on to the family’s drive.

Here, we could only guess where the family might be gathered on this holiday. Amish often live three or four generations at a time clustered in several houses on one farmstead. It isn’t unusual to find a large, main farmhouse, a smaller “grandpa’s house,” and a mobile home all grouped together to shelter parents, grandparents, and married children. We tried the main house, knocking on the door, but getting no response.

Worried that the pickling juices would freeze, we pushed open the door and set down our gifts on the long dining table—massive, oak, and draped with a plain white cloth. Chairs were pushed out and left at odd angles, as if the occupants had been suddenly called away. I felt as if any minute someone would step out of the kitchen and catch me here, a voyeur, a violator. The very house seemed alive, driven by the heartbeat of the pot-bellied stove in the center of the room, its hot air wafting toward us in waves.

Black socks, tights, and diapers hung clothespinned and drying from cords that stretched from wall to wall. A quilting frame took up the rest of the space, a star pattern just beginning to be embellished by tiny, regular stitches. Above the frame, a hook marked a prominent place in the ceiling where at night a kerosene lantern hung, casting its light on the artistry below.

We tiptoed out, whispering, as if fearful of being found, and climbed back in the cart. Just then the grosmomie rounded the barn, shawless, her bare arms crossing her chest. “Won’t you come in and have a cup of coffee? We’re all in the little house,” she called.

We thanked her but explained that we had eight more households to visit so would return another time. Inside the little house, the adults waved and a bevy of small Amish faces pressed to the window as Emily whinnied and retraced her route past the store. We trotted on through the afternoon, the wind stinging our faces, our double-socked feet growing colder and colder, the cart straining to creak up the lanes and turn in the drives, making sharp turns around windmills and pumps.

Sweat trailing down her flanks, Emily kept up her pace through the countryside. We surprised the families of the cheeseman, the horse trainer, the painter, and the turkey farmer who brings us dressed birds—heart-attack victims, scared to death on round-up days. The smaller Amish children, solely German-speakers until school age, bashfully clung to their mothers’ skirts when we offered them pretty ribboned boxes. They smiled excitedly when they found huge goose eggs inside. (The next day, a ten-year-old boy stopped, pounded on the door, stocking cap pulled over his eyes, and asked if our gifts were “fertile.”)

Some of the older children even seemed anxious to volunteer a list of their Christmas spoils. As we left the last house, our fingers just beginning to go numb, a seven-year-old boy stood on the mud porch, the door flung wide, and shouted after us, lisping, “I got a manure spreader!”

Home, Emily found her way to her stall, her blanket cinched around her rib cage, the sun setting behind the barn, bringing the day to a close in a hushed grey tone. A few flakes of another wet, won’t-last snow landed on the garden fence and the dried relics of cucumber vines that still twined up the wire.

It was just a few days later that we had that strong overnight blizzard. It gave way to an afternoon of blazing sunshine and cold. Now it’s evening. The sunset streaks the sky magenta and blue. The garden gate casts an eerie last shadow on the drifts inside, shiny with crusted snow.

In town, people are still digging out driveways and scraping sidewalks, regretting the cancelled basketball games, the missed profits at the stores. Out here, I see nothing but gain, the snow a blessing, the hope of an end of a cycle. Out here, the snow means faith in a bountiful garden to come, faith in the charity it will create to bond neighbor to neighbor. At least this evening, when I pull up my comforter, I’ll feel my head a little lighter on the pillow, knowing nature has settled some of its debts. Knowing some of my own have been paid. ❖

This article was published originally in 1992, in GreenPrints Issue #12.

Previous

Previous

Beautiful story that embodies the heart of Jesus to pass on the love He gives to those with a grateful spirit.