Read by Matilda Longbottom

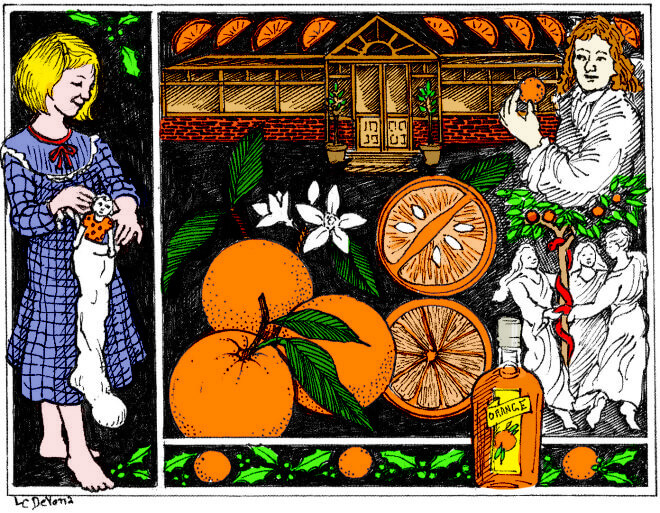

When I was a child in Britain, our Christmas stockings always had an orange in the toe. This wasn’t just a symbol but a real treat because I was a “war baby,” and oranges, which had to be imported, were rare. Even though oranges are at their best around Christmas time, I don’t know if American children still get them from Santa—I suspect not, because these days most of us take this marvelous fruit for granted.

Oranges came late to the Western world. The bitter, or Seville, orange came first, brought by Arab traders and used for medicine and perfume. The Moors took these oranges to Spain where they were often planted in Islamic gardens as a symbol of life, for their leaves are evergreen and they bear fruit and fragrant white flowers at the same time.

Sweet oranges didn’t come west until the 17th century, although they had been cultivated in China for centuries. Their botanical name, Citrus sinensis, means “of China.”

Orange trees need a warm climate (and good drainage) and couldn’t be grown in much of Europe, except in “orangeries”—special houses where the trees, in large pots, were wheeled inside during cold weather. Little orange trees make lovely houseplants, and I have one in my window now, sweetly scented and dangling with tiny fruits.

An early English orangery was visited by diarist Samuel Pepys on June 25, 1666. He wrote, “There I first saw oranges grow … I pulled off a little one by stealth … and eat it.” Oranges, which travel well, may have been imported by Pepys’s time, because a few years later he wrote that he tried orange juice and “it being new, [I] was doubtful whether it might do me hurt.”

We know now that orange juice, far from hurting us, is recommended as a part of our daily breakfast. Much of the American orange crop is pulped for juice, and it’s hard to believe that oranges, which grow so abundantly in Florida and California aren’t native there. But Spanish explorers took them to Florida, and Catholic missionaries carried them to California.

Oranges are truly miraculous fruits, neatly segmented by nature seemingly so we can eat them with maximum convenience. An orange is technically a berry, called a Hesperidum, after the golden apples in the garden of the three nymphs, Hesperides—guarded by a serpent that Hercules killed. Renaissance painters sometimes depicted oranges, not apples, on the tree that tempted Eve, although they couldn’t have been growing in Israel in Biblical times, much less in Eden! These days, however, oranges are an important crop in those parts: “Jaffa” oranges are exported worldwide.

Oranges get their names not from China but from the Persian naranj. Once we talked about “a narange.” Now their name, “orange,” is used both for the fruit and a color. Surprisingly, oranges don’t have to be orange-colored to be ripe. They only turn orange if the weather cools and become no sweeter when they do. Sometimes, though (and perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised), oranges are picked green and then dyed.

The color orange, both in nature and in dyes and paints, was known before the fruit came into our lives, but not given a name. It was often called tawny. Chaucer described it as “betwixt yellow and red.” The famous Orange men of Ireland got their name in a roundabout way. It came from a Roman town in France first called Arausio and then Orenge, or Orange. The Emperor Charles V, as a reward for services, gave the area to a Dutch prince, and the family was then known as the House of Orange. When William of Orange came to the British throne, after defeating his Catholic rival, his followers were known as Orangemen. Some of these Protestants came to America and named places where they settled—such as Orange County—after their loyalties.

Orange is a secondary color, a mixture of red and yellow, and probably in the past not nearly as bright as our modern chemical dyes can make it. It’s a bold color to wear, often used as an alert signal, as in lifejackets or prisoner’s jumpsuits. The color orange in nature can be a warning signal, too. Bright orange monarch butterflies warn the unwary bird not to swallow one or be poisoned. For humans, coloring food orange seems to have the reverse effect. My family prefers bright orange cheddar cheese, colored with annatto (a dye obtained from the seeds of the Bixa tree of South America). Many of the foods we eat are made toothsomely orange with annatto.

This is a time of year when I like to treat my family—so there will be lots of orange cheddar cheese for their grilled cheese sandwiches when they come. There’ll be a bottle of sweet orange liquor from France to pass around after Christmas dinner. They are all a bit old for Santa these days, so there won’t be stockings by the hearth. But there will be oranges, lots of oranges. We’ll never be too old, or too jaded, for oranges at Christmas time. ❖

This article was published originally in 2008, in GreenPrints Issue #76.

Previous

Previous

We grew up in upstate NY and one of my fondest memories of Christmas was getting an orange in our stockings on Christmas morning. Thanks for sharing a memory and reviving one of mine.

I grew up in England in the 50s and 60s and we, too, always had a juicy orange at the bottom of our Christmas stocking (although we had pillowcases, not stockings!) I rarely ate them at other times of year and always enjoyed my Christmas orange.