Read by Michael Flamel

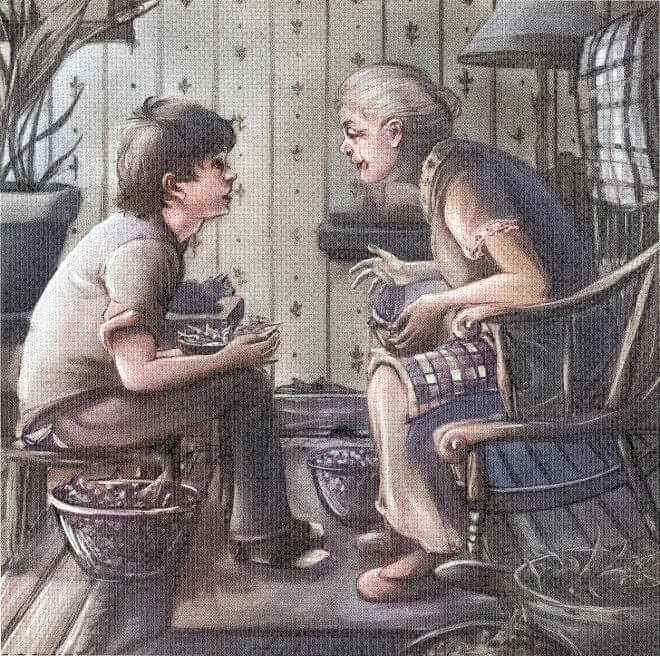

Her white hair was put up in a bun, and her pink cotton housedress reached down to her ankles. She sat in an old wooden rocker with a large glass bowl in her lap, gently rocking back and forth. Tubs of freshly picked peas were scattered about the living-room floor. One at a time, she and I pulled long, purple-hulled pods from the tubs, picked out the peas inside, then threw the peas into one bowl and the hulls in another. Grab, shell, dump, toss. Over and over.

Grandma saved the hulls; she would compost them to help fertilize her garden next year. Dying gives rise to new life and all that sort of environmentalist jazz. The only problem with modern environmentalists is that they spend more time preaching about the destruction of the environment than they do shelling peas. Maybe if they did more of the latter and less of the former, the general public would accept their message more readily. Oh, well, I’m digressing from my story to preach myself. I’m as bad as an environmentalist! Please be forgiving. I will stay on track.

“Grandma?” I asked. She was actually my great-grandma, my mother’s grandmother on her father’s side, but in a rural town like Jigger, Louisiana, no one ever used fancy titles like that.

“Yes,” she said, looking up from her bowl. She rarely spoke unless spoken to. The peas need shelling. We were doing it. What was there to say?

“Grandma, why do you have such a big garden?” Every day when I got off the bus at my aunt’s house across the street, I would go over and help Grandma with her garden.

It was a lot of work, though. That’s why sometimes when she wasn’t looking, I slipped an unshelled pea in the tub of empty pods. There. That’s one less pea to shell, I’d think.

“Well, we got to eat, son,” she replied, opening a shell.

“Why don’t you buy your groceries at the store, like everyone else?”

“Stores may not always be around.”

“What? No stores?” I was 12 years old. There had always been stores. There always would be.

“When I was a little girl, there weren’t any stores. We went to a market every now and then, but you can’t go to a market if you don’t have money.”

Creak, creak, went the old rocking chair. Grab, shell, dump, toss, went Grandma’s fingers. In her mind, the topic was discussed. But I was intrigued.

“You didn’t have stores? How did you get food?”

“Weren’t always food on the table.” She emptied a pod.

“Wow.” I knew what being poor was—we were poor. I knew that we must be when Dad ran over a rabbit driving home from church. He stopped the car and threw it in the trunk so we could eat it. Plus we got free lunch at school. But real hunger? I had never encountered that. I had seen pictures of starving black kids in Africa in National Geographic, but white kids in America?

“So that’s why you grow a big garden? Because you were hungry?”

“Yep, that’s why.” Grab, shell, dump, toss.

“Is that why you have so many fruit trees?” Her place was filled with them: plum trees in the front, pomegranates on the side and back, pears in the chicken yard, and apples near the garden. My cousins and I would just walk through her yard, pick, and eat. It was like our own little Garden of Eden. I’d always figured that Grandma just liked to garden.

“Yep, that’s why.” Grab, shell, dump, toss.

“Wow,” I said again. I pictured, well, I don’t know what I pictured. I was scared to ask, though. Grandma was always so solemn, so matter of fact and let’s get things done. She was never one to tell stories. Still, I really wanted to know …

“What was that like, Grandma?”

I don’t know if it was the quiver in my voice, her getting more mellow in her old age, or just the fact that I had never really asked about her before. But Grandma looked at me and her eyes began to soften. She leaned back in her rocker and her head tilted to the left, as a memory from the past began to take shape in her mind.

“Well, I remember this one Christmas,” she began. I was going to get a story out of her! I leaned forward in my chair to listen. She looked at my hands and then at the tubs of peas on the floor. Guess I was supposed to shell and listen at the same time. Grab, shell, dump, toss.

“My father was a fisherman, and the catches had been pretty slim. We didn’t have money to buy food, much less presents.”

No presents at Christmas? I thought. How horrible.

“We had been rationing our food for some time now,” she continued, the chair creaking. “One onion a day. That was our breakfast, dinner, and supper.” She looked over at me to see my reaction. “Doesn’t sound too good, does it, boy?” she said. “Well, that was all we had. It was either that or nothing.

“Now it was Christmas Eve, and we had eaten our last onion. Christmas morning, we woke up hungry and with nothing to look forward to. The cupboards were bare.” She shook her head softly. “My daddy had tears in his eyes when he gave me my Christmas present. It was a little doll, made from a corn cob. He had taken the corn shucks and made a little dress for her. He used the silk for her hair. ‘Here you go, Katie,’ he said. ‘I hope you like it.’”

She paused and dabbed at her eye with a kerchief. “It was the best he could do, you see. We just had nothing.” She put the kerchief back into one of the deep front pockets on her dress.

“Don’t worry, the story gets better now. You see, my momma’s older brother came over that day. They lived a few miles away, and as he walked, he scared up a couple of rabbits that he managed to kill with a slingshot. My uncle was great with a slingshot. Then about a mile from our house, he ran into my daddy’s brother, who was bringing over a sack of flour. It was about noontime when they got there, and I’m sure our bellies were growling. We were so happy they showed up. We had meat, homemade biscuits, even a little gravy. We were in tall cotton. It turned out to be a pretty good Christmas.”

Grandma didn’t say anymore. Neither did I. I had been stunned into silence.

For a few minutes, we silently shelled more peas. Then I bent over to my tub of cast-off shells and picked through it until I’d found all the full pods I had thrown away earlier. I put them on my lap and began shelling them.

Grandma didn’t say a word.

But there was just a hint of a smile in her eye. ❖

This article was published originally in 2011, in GreenPrints Issue #88.

Previous

Previous