Read by Matilda Longbottom

We put in a strawberry patch this year. Nothing huge, you understand: maybe 4 feet by 20, a nice strip along the fence on the upper side of the barn. Thirty strawberry plants. Ever-bearers, the kind that are supposed to start spitting out strawberries in June and to continue, irrepressibly, through September. The strawberries all did just fine; it wasn’t plants that turned out to be a problem here.

It was ground.

Our present garden is in central Massachusetts, a mere 25 miles south of New Hampshire (“The Granite State”), an area famed for rocks. I dug 287 rocks out of that strawberry patch. That’s not how many rocks were in the strawberry patch, because-after the first 150 rocks or so-I got a lot more discriminating about rockpicking. Right there at the beginning, I eliminated anything bigger than a ping-pong ball. No strawberry plant of mine, if I had anything to say about it, was going to wrap its tender roots around a rock. Inevitably, though, reality set in-rockpicking, after all is NO FUN, which is why criminals are always being made to do it when they’re not stamping license plates. It gets you in the small of the back. And, conveniently, just as your back starts to twinge, you begin to remind yourself that roots are powerful little buggers, capable of cracking concrete sidewalks and tearing up sewer lines, and there fore a few cannonball-sized rocks probably won’t hurt them. In this frame of mind, you cram the last couple of strawberry plants in between a pair of stubborn-looking boulders and go back to the house for iced tea.

All this, of course, might have been different if those 287 rocks were the very first rocks hauled out of the garden. But they weren’t. By the time I got to the strawberry patch, we’d already planted peas, onions, beans, lettuce, potatoes, carrots, beets, zinnias, and three kinds of basil, digging rocks all the way. At first we disposed of the rocks by throwing them over the fence into the field where the horses live, but-at three-and a-half rocks (minimum) per square foot of garden-it quickly became clear that we were paving the horse field, and the horses were starting to clump around just out of rock range and give us dirty looks. After that, we began simply piling the rocks up around the edges of the garden, a time-honored and traditional regional activity, which explains why New England is so full of old stone walls. Plant strawberries in Massachusetts and you get a whole new slant on those old stone walls. Behind every one of them, you realize in a burst of startled compassion, was an annoyed gardener with a sore back. It’s one of life’s little links with the historical past.

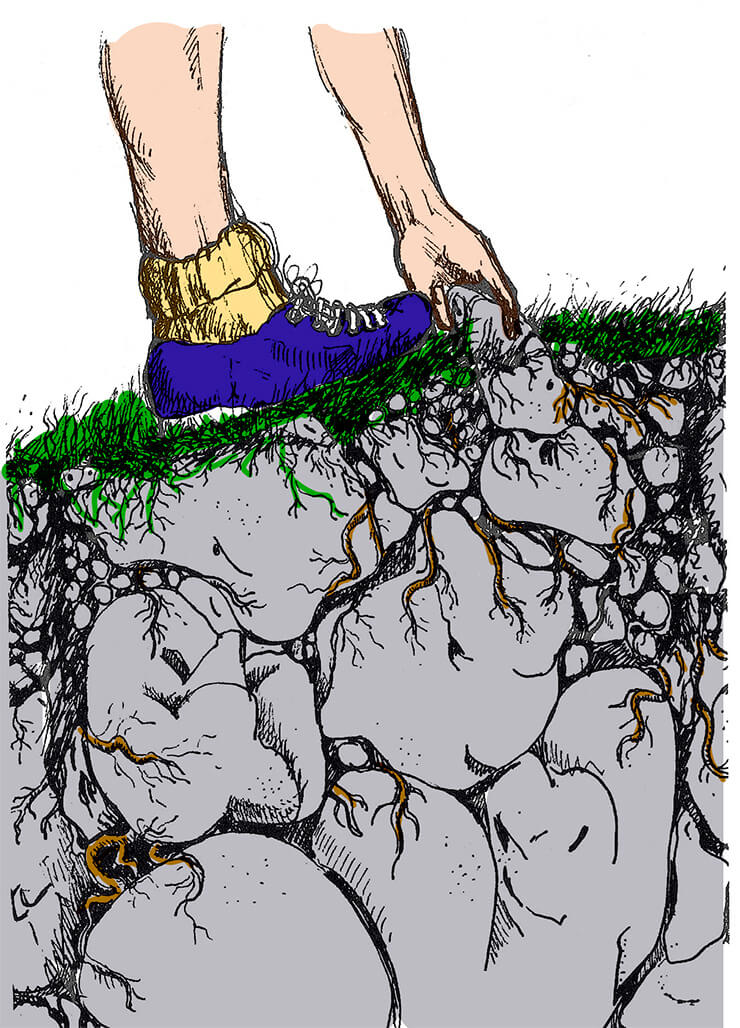

The worst part of all this is that the rocks, once picked, don’t simply go away. More of them appear every single year. Massachusetts, geologically, is a vast glacial rock dump; rocks, abandoned by retreating ice sheets, are seeded through its soil like raisins in pumpkin muffins. Not all of these glacial dumpees are little rocks, either: We’ve got some in our lower field the size of junked Volkswagons and there are some truly spectacular specimens, the size of your average two-bedroom bungalow, over on the grounds of the local Audubon Society. These monster rocks, though, don’t bother me. They stay put; we go around them. Our problem is the little stuff. The raisins.

Every year here, with the advent of winter, it gets cold. Birds hightail it south; the ground freezes: It snows, and the mailman leaves nasty little governmental notes explaining the proper way to plow out a rural mailbox. The children lose innumerable mittens, which pop up in the springtime, like crocuses, under the bushes. And out in the garden, deep under, the ground expands and contracts, heaves and ripples with freeze and thaw. As it does, buried rocks move. They tum and wriggle and rise, boosted inevitably up toward the surface, where they lurk, waiting for the first stroke of the springtime hoe.

There’s not, I realize, a lot that can be done about this. It’s one of the unavoidable evils of winter: the water pipes in the barn freeze; I have a birthday-an occasion which diminishes somewhat in charm and excitement with each passing year; and the garden breeds rocks. The trick is to carry on, in spite of snow, sleet, advancing age, and burgeoning glacial rubble. Building walls. Gardens.

And character. ❖

Previous

Previous