Read by Matilda Longbottom

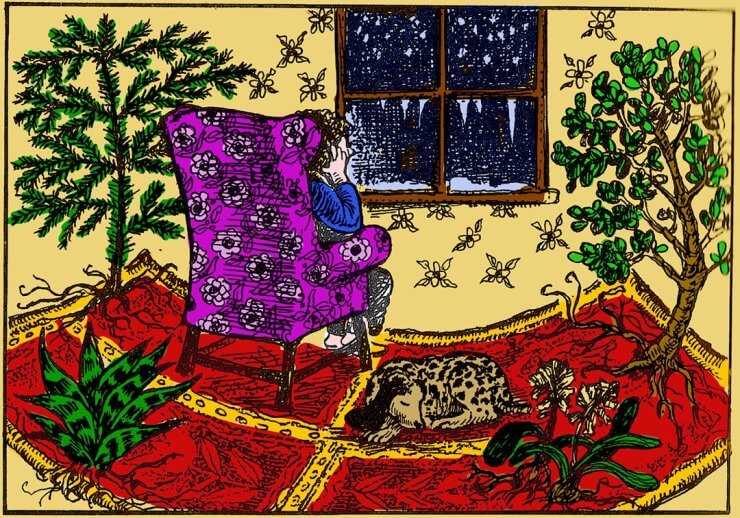

Bringing the garden inside is not a new idea. In the little city courtyards of Pompeii, frescoes enlarged the space with painted trees, flowers, and birds. In the Arabian deserts, nomadic tribes would remind themselves of oasis gardens by spreading ornate carpets, patterned and quartered like oriental gardens, on the hot, sandy floors of tents. We, too, in the bleakness of winter and the aridity of cities, create inside gardens, not only with flowered curtains, carpets, and wallpaper, but by actually bringing the plants themselves inside.

There is no question that flowers in winter are immensely cheering. I usually manage to have a bowl or two of hyacinths, and I have a sunny window where I keep some old members of the family like the orange (or lemon or grapefruit) tree that my son, now in college, grew from a pip when in kindergarten. I keep hoping that the tree will go to college or somewhere, too. It gets bigger every year and is covered with spines, but so far it hasn’t blossomed or borne fruit.

I understand from my books that citrus trees, like primates, are slow to mature, and if you want fruit from your own little lemon tree, you had better get a grafted tree from a nursery. But I still remember my son’s face when the pip sprouted and he ran in to show me. He doesn’t care what I do with his lemon tree (or is it a grapefruit or an orange?), and he no longer comes to me aglow with the wonders of life or needing comfort from its vicissitudes.

That’s why, I suppose, I continue to tend the tree. There’s a jade plant, too, which my mother-in-law bought 40 years ago. It used to flower sometimes, but now most of it is covered with a climbing jasmine, which so far hasn’t flowered. I bought the jasmine one March at a flower show and put the little pot onto the dirt beside the jade plant, and then forgot it.

Two months later, they were inextricably entwined and all I could do was to dig a hole under the pot and bury the jasmine’s roots. Now it and the jade are inseparable until death do them part. I know there won’t be fruit from this union, but I still hope for flowers from one or the other. I can never understand why you can smother some plants with love and care, read instructions on how to cultivate them, and they die.

Others you can neglect completely and it only seems to encourage them. Houseplants particularly seem to follow this pattern. We had a gardenia once which we tended most lovingly, and even swabbed its leaves individually to rid it of mealy bugs, or whatever it is that gardenias get, but it died anyway. Meanwhile the lemon? and the jade and the jasmine flourished, and we had to get rid of a Norfolk Island pine rather than cut a hole in the living room ceiling to accommodate it.

A trailing thing another son gave me on Mother’s Day seems to be nourished entirely from the letters “I Love you Mom” and a heart on the too-small plastic pot where it lives. I occasionally chop hunks off it, but it doesn’t mind that, either.

The cultivation of indoor ornamental plants only became really popular in Victorian times. In 1833, new manufacturing methods resulted in good-quality sheet glass becoming available. In 1845, the glass tax in Britain was repealed, making large windows and greenhouses affordable to more people. In addition, the 19th century saw the introduction of steam heat and central heating and the importa- tion of new and exotic plants from exploration abroad. Hot houses, parlour plants, and conservatories became popular on both sides of the Atlantic.

The stuffy Victorian parlour was excellent for tropical plants. Nowadays, glass is cheap but heat is expensive again, and most of us can’t afford greenhouses or conservatories. I have one south window where my indoor plants live (or don’t live), and we keep our house rather cool, so I don’t try to grow exotic tropicals but not only because I haven’t the right conditions.

Someone gave me an orchid once and it bloomed for months, pure and utterly beautiful, seemingly without effort or nourishment.

It seemed, as Frederick Boyle, a 19th century writer on orchids, said, to have been “the latest act of creation in the realm of plants and flowers” and “expressly designed to comfort the elect of human beings in this age.” Maybe that was the trouble.

There was I bustling around, picking up sneakers, running the clothes washer, and fussing in a thoroughly Western and non-elect way, and it simply glowed with the manifestation of being, the beauty of tranquility.

I suppose I should have sat down in a lotus position in front of it, instead of finding it slightly irritating. In the end I left it outside too long one fall, and even it couldn’t cope with the essence of a frosty night.

Bonsai have the same effect. I am really willing to be transported into a miniature, perfect landscape where time stands still, but I wish the mail wouldn’t arrive with an unpruned insurance payment bill just when I’m getting into the swing of it. I seem to do better with the untidy, impractical passion of the jasmine intertwinerl with the jade.

Cacti, however, fit quite well into our household. One son had a cactus plant which I cursed regularly. It resided on the playroom table, usually half-smothered under a heap of toys, paper, and pencils.

It was covered in dust, and whenever I tried to tidy around it, tiny spines would shoot out into my fingers and remain there for days, too small to be removed.

Nothing, not even my curses, seemed to kill it. It did not mind the toys and the dust and was practically never watered. When I suggested that it might be happier somewhere else and that nobody “took care of it,” there would be vociferous protests.

He loved it and had been intending to water it that very day.

Then he would be so generous in his compensation that rivulets of water would flow like desert floods over the edge of the pot, between the toys, through the paper.

Pencils would float onto the floor and, once again, the cactus would not die.

Then, one day, it flowered. It did so with no warning and no apparent reason. Suddenly, from out of its fat, dusty side, as if stuck there with a pin, appeared an exquisite blossom, evanescent as a butterfly and of a tender sunset hue. It lasted just one day.

Then it dropped off like tissue paper and we had only its musty monstrosity of a parent to care for again. We have sweet records of the excitement in Victorian parlours when the night-blooming Cereus flowered. This plant only blooms once a year, and its blossoms do not open until about 9 p.m. It takes about two hours for them to open completely, they are nearly a foot in diameter and are also fragrant. By morning they are gone. We, who experience revolutions, death, sex, and everything else on television’s windows to the world, might not find the two-hour opening of a blossom as exciting as our ancestors did, though, speaking for myself, I would love to see it. The Victorians, however, thought the event worthy of invitations to neighbors to spend the night watching.

It was an era when nature, fast disappearing with growing industrialization, became less accessible and more desirable. The cultivation of plants, easier indoors for crinolined Victorian ladies, was considered healthy and romantic. The conservatory, the scene of romantic trysts, was an enchanted bubble containing a perfect world of exotic plants. But the creators of such conservatories were destroying the natural world as fast as anyone else. There was apparently an insatiable market for plants from abroad, and collectors stripped the wilderness. Orchids were usually gathered by cutting down the tree on which they grew and taking a portion of it home.

Very few survived the journey, and so more still had to be taken. A contemporary complained in 1891 that “most of the orchid-growing portions of the world have been ransacked and their natural habitat left bare.”

We may be more wary of pillaging the wilderness but, we are told, the pollution problems we have created may one day force us into hothouses. Modern scientists produce plans of whole towns under bubbles of controlled environment. Some 20 years ago, I saw such huge greenhouses. I was on a tour of Iceland, accompanied by my fourth and fifth sons, aged less than one and three years old. A part of our tour was of huge greenhouses, heated entirely by thermal springs.

The tour, I soon perceived, was to encourage tourists, but not tourists like ourselves. The guide, an impeccably beautiful Nordic blonde, greeted the children and their paraphernalia of bottles, diapers, teddies, and applesauce with less than enthusiasm. As the day wore on, I could see that their infant antics awoke no chord of motherliness in her perfect bosom. Indeed, I believe I caught her gazing musingly at the tundra when they screamed, as if contemplating dumping us out of the bus.

When we arrived at the greenhouses, I was covered in a thin film of applesauce, and the children, who had been awake most of the previous sunny arctic night, were fretful. We trailed after our guide, who pointed out one horticultural wonder after another. Finally, we came to the piece de resistance.

“Would you believe it?” she said. “We have here a banana tree, growing in the heart of Iceland!”

There, indeed, was a banana tree, weighted down with a glorious pendulum of ripe, yellow fruit. The children clamored for a banana. The guide gave us a withering look and passed into the next greenhouse, followed by the other sedate and attractive tourists. At this point, Son Number Five, with a beatific smile and an animal enthusiasm of which only he was capable, noisily produced an extremely dirty diaper.

Did I do wrong? There was no facility around, and I was far too terrified to ask the guide for help.

Hurriedly, I removed the diaper, dug a hole with my hands, and buried it under the banana tree. I wonder sometimes if the bananas were even better the years following, but we never returned to see.

The years have passed, and those sons are grown now.

I am left in my living room, warmly protected from winter and accompanied by the citrus tree that will never go to college, the barren love of the jasmine and the jade, the little plant which grows on love alone and three blue hyacinths which have successfully flowered but are top-heavy and have to be supported by a chopstick.

It is a safe world, but imperfect, like many greenhouse worlds, and, to compensate, I have furnished it with next year’s garden catalogues. From the illustration on the front cover of one, it appears that I can have daffodils, platy codons, stocks, phlox, daisies, chrysanthemums, nasturtiums, marigolds, and lilies-of-the-valley not only all in the same place, but all at the same time. Now there’s perfection for you.

I shall buy some of it tomorrow. ❖

Previous

Previous

PS, I forgot to add, that I can only grow from hydroponic units now and they are absolutely wonderful and will grow amazing crops, indoors! I just harvested an entire 6 pod unit of Bok choy that I’ll be making into stir fry for the evening meal, with added other green cabbage and vegetables to serve over rice! You may want to try a unit for your home, they are easy and amazing!

This is great, I loved it! You got a laugh from me when I read of your burying diaper “remnants” under that banana tree, oh ha, ha, ha! I’m glad your tour host didn’t see that one and only a crafty mother could get away with it. As far as lemon trees from pips go, I once did that, waited 20 odd years only for it to produce navel oranges… and I could have sworn I labeled it properly-and it sprouted in a plastic drink cup in the kitchen window before I even had a yard to put it in! Wonderful writing, thank you for that laugh!