Read by Matilda Longbottom

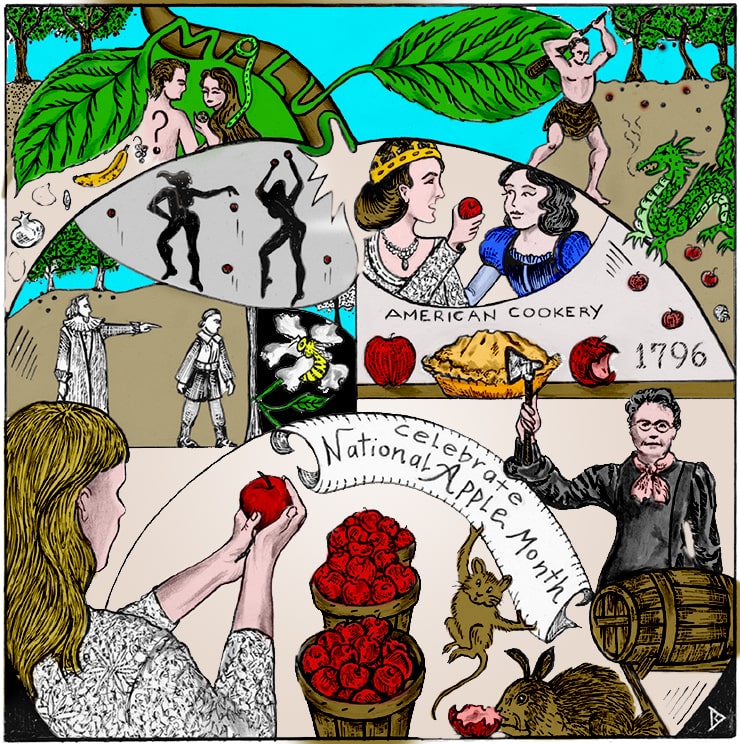

Apples have a bad reputation dating back to the Book of Genesis. And we’re never going to let them forget about it, either, since we’ve immortalized their part in the Garden-of-Eden fiasco in scientific Latin. The generic name of the apple is Malus, from the Latin for bad, as in malicious, malevolent, and that creepy fairy Malificent.

I like apples and I don’t think they deserve their bad press.

It seems particularly unfair, since these days botanists and biblical scholars agree that the fruit that Adam and Eve so dis-obediently ate probably wasn’t an apple at all. That said, they don’t agree on what the mysterious fruit actually was. Various guesses include the fig, the date, the apricot, the grape, the citron, the carob, and the olive—which last, at least, seems unlikely. In the fresh-off-the-tree untreated state, olives taste awful; the First Couple would immediately have spat them out and saved themselves a lot of trouble. Dan Koeppel, author of Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World, argues that the forbidden fruit was a banana, an opinion that was shared by no less than Carolus Linnaeus; and there’s a hefty contingent of fruit fans that opts for the pomegranate.

Much of this fruit guessing depends on where the guesser thinks the putative Garden of Eden was located. Traditionally, Eden has been imagined as flourishing somewhere in the Middle East—which puts apples neatly out of the picture, since apples originated in Kazakhstan in Central Asia. (Alternative proposed locations for Eden include such locales as Mongolia, Ohio, and the Bermuda Triangle.)

Traveling overland from Asia, apples reached Europe by ancient times, where—according to Greek mythology—they caused Hercules a lot of trouble (to get at them, he had to bash a dragon with a club), lost Atalanta a crucial race, and started the Trojan War. By the fourth century BCE, according to the playwright Aristophanes, apples were common enough to be tossed to favored clients by dancing girls in brothels. “Tossing apples,” in ancient Greek, thus soon became a catchy euphemism for sexual intercourse—remember this the next time you’re in an apple orchard—and it may be Greek slang that led to a lingering European superstition that eating apples could make one pregnant.

Medieval Christians—who teetered among figs, grapes, and apples in early representations of forbidden fruit—finally settled on the apple, which has since served as the symbol of original sin. By the time John Milton wrote Paradise Lost in the 1660s, the apple was firmly established as a bad guy—and as such, it’s worked its way into our folklore. When the wicked Queen did her best to kill Snow White, you notice that she didn’t poison a pear, a peach, a plum, or a quince. She poisoned an apple.

Given the apple’s immoral aura, it may not be surprising that Episcopalians—not the straight-laced Puritans—first brought apples to North America. By most accounts, the first apples in the colonies were planted on Boston’s Beacon Hill by an Anglican minister named William Blaxton (or Blackstone), who arrived in Boston Harbor in 1623, along with several boxes of books and a bag of apple seeds. His congregation gave up within the year and ran for home, but Blaxton stayed behind, comfortably settled in his cabin, surrounded by books and an orchard of infant apple trees. He remained there, solitary, for seven years, reading and developing the New World’s first named apple variety, Blaxton’s Yellow Sweeting.

This horticultural idyll ended abruptly in 1630 when 17 boatloads of Puritans arrived, under the leadership of John Winthrop—and none of them wanted anything to do with a presumably less-than-saintly Episcopalian. Blaxton was summarily banished to Rhode Island. The Puritans took over Beacon Hill and the orchard, and notably improved Blaxton’s crop by importing pollinators in the form of English honeybees. Eventually Winthrop, hopefully ashamed of himself, forwarded some bees to Blaxton in Providence, and also sent along his books.

By the 18th century, most American farms boasted apple trees. The first recipe for the all-American apple pie appeared in American Cookery, the first American cookbook, published by Miss Amelia Simmons (credited on the cover as “An American Orphan”) in 1796: It called for stewed apples flavored with grated lemon peel, cinnamon, mace, rosewater, and sugar, baked in a “paste.” New Haven tradition holds that Yale students were served apple pie for supper every night for an unbroken 100 years—and a lot of New Englanders (including my granddad) routinely ate apple pie for breakfast, with cheese.

Dried-apple pie, the crust rolled out on the wagon seat, was a staple of the wagon trains. This didn’t suit everybody; one unhappy eater left behind the condemnatory verse: “I loathe, abhor, detest, despise/Abominate dried-apple pies.”

The vast majority of early American apples, however, went into hard cider. The usual farmhouse cider barrel held fermented cider, a brew that contained about 8% alcohol, which doubtless explains its traditional use as a cure for “melancholy.” For those who wanted even more bang for their buck, a beverage called applejack could be made from hard cider by a rough-and-ready process of fractional crystallization: freezing. As more and more water, in the form of ice, was removed, hard cider was converted to an even more alcoholic drink, said (by some) to taste just like Madeira wine. Really frigid winters could produce a truly phenomenal applejack, with an alcohol content of up to 30%.

The temperance movement, which began in America in the 1820s, promptly zeroed in on the apple. The only decent course for Prohibition orchard owners, according to “What Shall I Do With My Apples?,” an inflammatory temperance tract of 1827, was to burn their trees down. Every barrel of cider, the author thundered, is “enough to ruin a soul, if not destroy a life.” Cider, in fact, was even worse than rum. Rum, the tract continued, quoting the nameless wife of a cider-drinker, “laid him prostrate and helpless on the floor,” while cider “gave him the rage and strength of a maniac.” Carrie Nation had a hatchet because she was after the ruinous cider-producing apple trees.

Luckily, commonsense prevailed and (most of) America’s apple trees survived.

Fall, of course, is the season for apples. October is National Apple Month—established in 1904 to “enhance consumer awareness and usage of apples”—though you pretty much can’t help being aware this time of year if you’re anywhere near an apple tree. The apples are cold and crisp and delicious; and the smell of them is the smell of autumn, the essence of those bright blue days before winter shuts us down. “You are new like nothing/and no one,/always/freshly fallen/from Paradise,” writes poet Pablo Neruda in his “Ode to Apples.”

Apples—well, yes, they are tempting.

But—believe me—they’ve never been bad. ❖

Previous

Previous