Read by Matilda Longbottom

Buying Christmas presents for my young relatives is always a struggle. I only see these kids once every few years when I go back home to Texas. I can hardly keep their ages straight, much less their clothing sizes or their favorite toys and games. But it’s not just the fact that I barely know these kids that makes buying for them difficult. I also shop with a social agenda. I think kids today spend too much time in front of television and electronic games, so I want to get them something low-tech. Something educational, something that will encourage their artistic side, spark their creativity. And of course the toys have to be non-sexist, as if my gift of a doll or a toy tank will be the one influence that pushes them right over the edge.

“Then there was the time in second grade,” little Susie with the perfect cheerleader tan and low self-esteem will tell her therapist years from now, “when Aunt Amy sent me that doll that cried all the time. That’s when I learned that pleasing others was more important than taking care of myself!”

Or young Bobby, still clenching his toy tank: “I was on my way to a satisfying career as a preschool teacher, where I would provide that role model of a tender, nurturing male so often missing from young children’s lives. Then Aunt Amy sent me a toy tank, and I killed all my sister’s dolls! Now I’m a bounty hunter.”

So, as you can imagine, Christmas shopping is not easy for me. After hours of wandering around downtown, lost and confused, I usually end up in a toy store with a list, asking for help from a store clerk. “Uh… I’m shopping for a seven-year-old, a five-year old, and two ten-year-olds. What do you suggest?”

“Boys or girls?” the clerk invariably asks.

I grit my teeth. “I’m looking for gender-neutral toys. So it doesn’t matter whether they’re boys or girls, NOW DOES IT?”

In any other part of the country, the clerk would have stared at me blankly and suggested I send cash. But this is Santa Cruz, and every local toy store has one of those sections. The politically correct toy section, complete with animal puzzles, save-the-rainforest kits, and storybooks with thinly veiled messages about self-esteem and cultural diversity.

This past December, I couldn’t find anything that appealed to me. So I went home and called my uncle to ask for suggestions for his kids. “Well, the teenager has quit talking to us and spends all his time locked in his room playing video games. You could send him a CD-ROM.”

Silence from my end. The teenager’s getting clothes, I decided.

“And the middle one is perfect. He’ll love whatever you get him.”

That’s no help. Clothes it is. “And what about the three-year-old?” I asked.

“She loves Barbie. We just got back from Toys R Us. I got her Dentist Barbie.”

“BARBIE?? How could you? Don’t you know that Barbie would have a 54-inch bust if she was full-sized? What kind of a message is that to send to a little girl?”

My uncle said helpfully, “They have every color Barbie. And she comes with a little girl, Kelly, who sits in the dentist’s chair. You can get any combination of races you want: Asian Barbie, white Kelly, white Barbie, African-American Kelly … ”

“Yeah? Well, do they have Doctor Barbie?”

“Yes, they do.”

“Corporate Attorney Barbie? Tenured Professor Barbie? City Planner Barbie? Social Worker Barbie? What about Gardening Barbie?”

My uncle jumped in. “Actually, they do have Gardening Barbie. She comes with her own tools.”

I gasped, then paused for a long moment. In a hushed tone, I said, “I want one.”

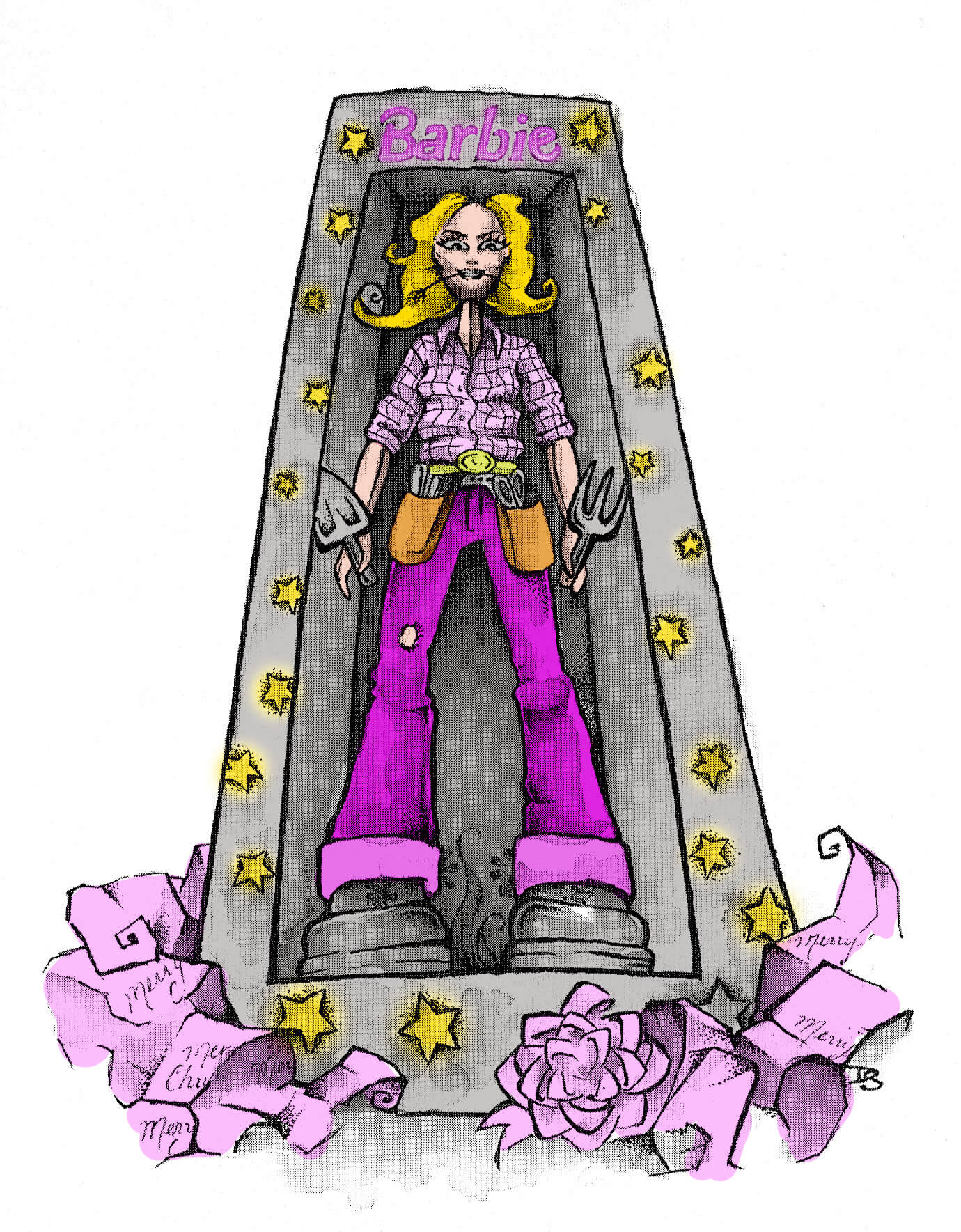

And that’s how, on Christmas morning last year, I found myself unwrapping a doll for the first time in decades. Gardening Barbie (and her assistant, Little Gardening Kelly) came packaged in a pink cardboard box, along with some pink gardening tools and a cardboard flower stand filled with cardboard flowerpots.

I don’t remember much about the Barbies I had as a kid. From my adult, feminist, analytical mind, I was shocked at the way Barbie was tied down to the package, her ankles and wrists bound as if she might kick free, a cord firmly around her neck, and all her hair stitched into the back of the box. Her pink gardening clogs dangled uselessly from her plastic feet, which were arched in a permanent high-heel position. Her floral gardening outfit offered no protection from the sun, and left her rock-hard abdomen exposed. Her perfect, creamy white hands clearly could hold no tools, but the kind folks at Mattel had added a sort of extra handle onto each tool, so Barbie could slide her hands inside and pretend she was holding them.

So now we know. Barbie gardens about as well as she flies a plane, teaches a math class, or pulls a tooth, which is: not at all. But isn’t that why we all fell in love with Barbie in the first place? Amidst a clamor of voices demanding that we go to school, get a job, be a success, Barbie has always been willing to stand tall and remind us that it’s not really what you do. It’s how you look.

All right then, I decided that if I can’t teach Barbie to be an actual gardener, I could at least show her how to look like one. First, I grabbed a pair of jeans and a workshirt, borrowed from Ken. Then a pair of combat boots stolen from G.I. Joe. And of course, a short, practical haircut: just the thing for life on the farm.

Barbie looks much happier now. She stands on a shelf with a few houseplants, her pink shovel in hand, looking as if she might just seed a row of sunflowers in the potting soil. She has, at last, found a purpose.

Next year I’m going to send this Barbie to all my younger kin. Then when that teenager computer-loving nephew grows up and becomes an organic farmer, complete with manure-caked boots and a pickup truck with a bumper sticker that reads, “My Other Car Is a Tractor,” we know who he’ll credit: “I owe it all to my Aunt Amy and that Christmas long ago when she sent me my own specially modified version … of Gardening Barbie.” ❖

This article was published originally in 1999, in GreenPrints Issue #40.

Previous

Previous