Feral pigs I could understand. Feral cats or dogs even. But feral marigolds? You just don’t expect to see feral marigolds.

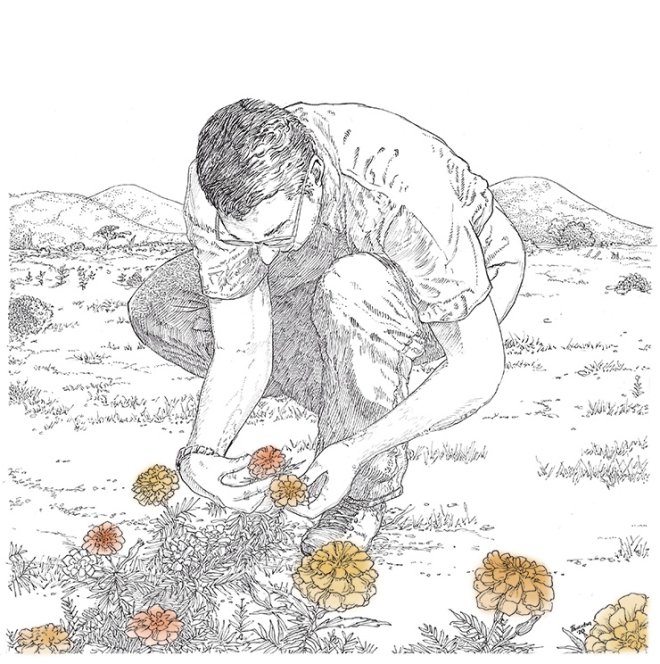

Yet there they were. A few small golden flowers just peeping from under the clumps of wild, windswept tall grass. The flowers had gradually lost their bright, domesticated brashness and reverted to their tiny wild size, but they were still yellow, still clearly marigolds.

They were all that remained of Mum’s beloved flower garden.

I had spent most of my preteen years living in houses in construction camps on the South Island of New Zealand, where my father ran canteens for the workers building hydroelectric dams.

Our family left our last camp when it was time for me to start high school. At each of her new homes, Mum had planted a flower garden. She loved roses and dahlias and daisies, but marigolds were always her favorites. “The color of sunshine,” she’d say with a smile. Everywhere she planted, she placed that band of cheerful gold across the front to welcome visitors.

It was over a decade before I returned to that last construction camp. I struggled up the familiar hill, but at the top there were no signs that anyone had ever lived there. Everything was gone. Construction camps are all temporary: the buildings are designed to be taken to a new site at the completion of each project. Where I stood, only wild grass and shrubs remained—nature’s recolonization was complete.

Yet there was indeed something there. The removal trucks had no interest at all in battered gardens, so they’d taken the buildings but left as worthless the once-precious flower beds. A very few flowers had survived: the marigolds. I had known the houses would be gone.

Their removal was just a part of a construction project cycle. So that emptiness had almost no emotional impact on me. But I hadn’t been prepared for the belt in the ribs I felt from seeing those tiny tough yellow flowers. Standing there in front of our vanished home and staring at the just-visible indicators of Mum’s delight in her flowers, I felt overwhelmed. Those small feral drops of sunshine told just a tiny fraction of our family story, but they were affirmations that, yes, we had lived here. I had been a child there. Without their shy presence, I would have blundered across the sheep pastures with no idea where my roots lay. The marigolds provided an anchor to history, a pathway into family memories.

At the end, Mum’s garden was her downfall. She fell and damaged her hip while pulling out a rosebush. This forced her into a nursing home. She grew to love it there, though, meeting many new friends (even, so we understand, a charming boyfriend). She kept a garden, as well. Then she broke her arm and never recovered. She was 96. Her church was filled with flowers when we said our farewells. Still, I should have gone back to the camp and collected some of those feral marigolds—so she could have taken a tiny bunch with her. ❖

Previous

Previous