Read by Matilda Longbottom

My brother’s birthday is in the autumn. He celebrates it with first visits to the beach, anticipation of summer, delight in spring. The children, he tells me, are looking forward to the long, hot holidays and their traditional Christmas barbecue. My brother lives Down Under, in Australia.

I used to wonder how he could bear it: the bath water running away in the wrong direction; the sun crossing the northern sky; spring when it should be autumn. We both grew up in Britain-where, as children, we thought Australia was the bottom of the world. But at least I didn’t have to change hemispheres when I came to Pennsylvania. Gardening, however, is beginning to teach me that it doesn’t really matter that much. We are always in several seasons at once.

“You ought to know that October is the first spring month,” says Karel Capek in The Gardener’s Year. It may seem that all is dying, but underground new roots are being formed, and above ground, buds, all getting ready for the showy side of gardening in spring. For winter is sleep, not death, as all gardeners know.

Poets may be thinking of death and prudent home owners of double glazing and central heating, but gardeners, idealistic and romantic as ever, are planting drifts of chionodoxia, or trotting foolishly round with clumps of divided perennials, trying to find a gap somewhere to put them. We do not throw them out and get on with planning the oil payments, for our minds are on spring. Indeed, instead of putting aside fuel money we behave as though winter never existed-we keep running out and buying “just a few” more bulbs for that dull comer we had forgotten when we sent out our bulb order in June. There is no excuse: Sometimes we are lucky enough to be married to someone who will chop wood or think about the oil bill.

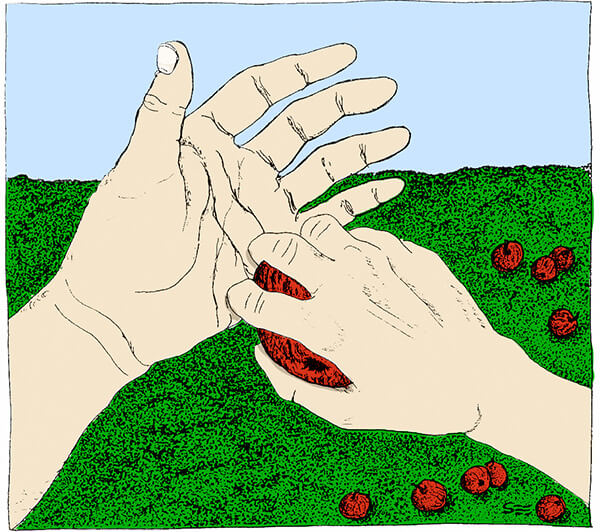

Fall, of course, is not only a season but a state of humanity, and gardeners from the very first have never been able to resist temptation. It was surely in autumn, the time of ripening fruits, that Eve successfully got Adam to take a bite. We read nowadays that men’s hormonal levels are highest in autumn, thus increasing their libido at that season. It all fits in very well with that seductive scene in the first garden. Tradition has it that the fruit was an apple, though some scholars root for pomegranates, figs, apricots, or oranges. As a so-called “organic gardener,” I feel it must have been an apple, because apples are where, for me, temptation and the non-resistance of it meet.

The most perfect apple in literature, that offered to Snow White, was poisoned. So perfect was it that she simply could not resist, though she really knew better. The merchant in “Beauty and the Beast” had a similar problem: an irresistible rose in a snowy winter garden. Nature disapproves of such things and, as an organic gardener, I believe in Nature.

My creed goes something like this: “I believe absolutely in Organic Gardening. I believe that poisons are ruining the environment; I believe in Mulch; I believe in Milky Spore; I believe in Companion Planting; I believe in Compost; I know, 0 Lord, that healthy plants resist insects; I believe in the spirit of Bacillus thuringiensis. I have done things I ought not to have done and I have not done things I ought to have done, but I truly believe in the protection of Safer’s Soap and I trust in the spirit of Nature.”

Blessed is the man ( or woman), however, who can see the perfection of the rose ravaged by beetles and not run weeping to the nearest garden center for poisonous spray. Even more blessed is he (or she) who can grow apples organically.

I planted a dozen dear little apple trees, thinking I wouldn’t mind sharing a part of some of them with the odd worm. But it was not a matter of sharing with Nature, Nature wanted them all. Now, I didn’t do sticky traps and painted balls and “non- poisonous” sprays because … well, because. I simply decided I would share. What happened was that I didn’t get a single apple, even the year that I sold my soul to the Devil. I didn’t even do that properly but applied sprays sporadically, at half strength. Thus, everyone was happy: the manufacturers of the sprays, the worms, the Devil, and the merchants who sold me the sprayed apples which I eventually had to buy. Only the environment and myself lost out. From the point of view of modem capitalist economy the experiment was a great success, but you see what I mean about apples.

My grandfather grew apples and loved his orchard with a passion. He was a doctor and tenderly bound his grafts onto the branches with yards of pink surgical tape. In those days of postwar Britain we did not get many sweets and I eagerly accepted the windfalls I was allowed to eat when we visited. I do not remember ever actually eating a whole apple. We were expected to “cut out the bad parts,” for the perfect apples were stored on slotted shelves in the cellar and one only got to eat those during the winter, when they were shrivelled and wrinkled, but very sweet. Grandfather did get some good apples, but there were a lot of rotted windfalls, too, which attracted yellow jacket wasps.

Like Gilbert White, two hundred years before him, Grandfather made traps from jars or bottles with a small en trance hole, luring the wasps in with a little irresistible jam or beer at the bottom. I used to watch them buzz furiously in the jar, hitting the edges of the exit hole again and again, and wonder that they could not just be still a minute and realize that by crawling up the sides of the jar and across to the little hole they could easily get out the way they had come in. They did not learn, but buzzed themselves to a fury until they finally lay feebly struggling in the liquid at the bottom, surrounded by the rotting bodies of no-less-foolish predecessors.

In autumn, we, too, go a little more slowly. In spite of everything, as Alan Lacy says in his excellent book, The Autumn Garden, “the season is imprisoned in a system of easy but misleading metaphors”. In other words, it is generally equated with the cycle, and therefore the exiting years of human life. In September, says Vita Sackville-West,”we approach seventy; and then comes October and November and December, when it would be tactless to pursue the analogy any further.”

Perhaps, though, that’s not all bad, even if we accept the analogy. Youth, like spring, can be giddy and exhausting, at least from the point of view of autumn. My Mother remarried at the age of fifty and I remember wondering why, at that time of life, she bothered. Wouldn’t she be just as happy, thought I (aged twenty), settling down with a book in the intervals between visits when we felt like coming home? Autumn is reassuring in that way. Rather than settling down, there is a quieter, though often brilliant, continuation of what has gone on before. Alan Lacy tells us he counted 75 flowers in bloom in his September garden but only 39 in the same garden in April. “I tell you,” says Karel Capek, “that this flowering of mature age is more vigorous and passionate than those restless and passing tossings of the young spring.”

So I, too, in my adopted land of young grandmothers, am not giving up, and I seem to reach for the scarlet autumn skirt rather than the ubiquitous black worn by so many women of my age in older, and perhaps more realistic, cultures. But even if I am a grandmother, “the obvious lesson of decay and death” (Dudley Warner) is not necessarily the lesson of autumn. For autumn is the season of seed-setting, the time when nature is thinking of future generations. Alan Lacy’s 75 flowers, like my autumn red skirt, are all very well, but the purpose of the whole thing was not flowers for our enjoyment but seeds for posterity.

I may be a remontant grandmother, and I am thoroughly enjoying my blaze before inevitable, if not imminent, senescence. I may understand now why my mother could marry at my age, but it’s my grandson, baby Simon, the apple of my eye, who’s going into the future. Without our children and without the seeds of autumn, there is no future. Perhaps we should look at the way nature puts everything into those seeds when we are told there’s not enough money for education, child care, medicine for the young. Nature doesn’t take risks like that. Those soft petals, alluring fragrances, dusky pollens, erect stamens, heady colors, and mad spring tangles were all for those funny little brown seeds we are seeing everywhere. Autumn flowers are pretty reminders, but now it’s too late for them to set seed. A truly successful autumn garden is full of seeds, seeds in wisps and tassles and berried clusters, of buds left above the brilliant leaf carpet, and of roots digging down, as children do, towards Australia. ❖

Previous

Previous