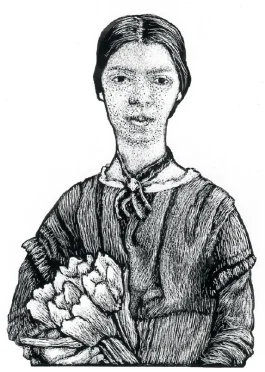

Emily Dickinson published almost no poems in her lifetime. She became more and more reclusive as the years passed, eventually seeing almost no one other than members of her family.

Most of us know this about the famous 19th-century New England poet. Fewer know she was a lifelong passionate gardener. She sent nosegays to visitors she wouldn’t meet. She kept an herbarium filled with 424 pressed, classified, and labeled flowers. A niece described her garden as having “carpets of lily-of-the-valley and pansies, platoons of sweetpeas, hyacinths, enough in May to give all the bees of Summer dyspepsia. There were ribbons of peony hedges and drifts of daffodils in season, marigolds to distraction—a butterfly utopia.”

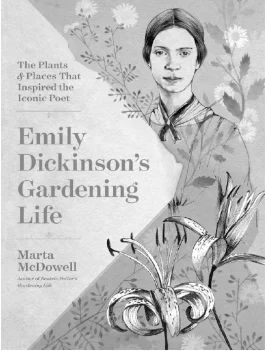

Now Marta McDowell, acclaimed author and former Gardener-in-Residence at the Emily Dickinson Museum, has shared Dickinson’s passion for gardening and its intimate connection to her poetry in her detailed and fascinating Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life. As McDowell puts it, “Looking out her window, [Emily Dickinson] stood witness to all the seasons in her garden, her ‘ribbons of the year.’ Whatever the month, her garden was inspiration for her poems. And her poems have proven perennial indeed.”

Here’s an excerpt, “A Selection of Emily Dickinson’s Spring Bulbs.”

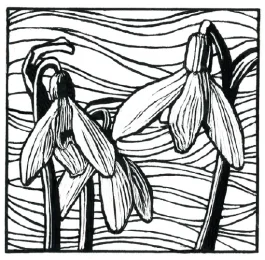

Snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis). Heralds of Spring, the snowdrops lead the way, their nodding, bell-shaped flowers with their own proclamations. Each flower has three inner petals trimmed in green and three outer petals that descend in graceful curves. They are sweet-smelling and long-lived. As a bonus, snowdrops that are happy in their spot increase every year, carpeting an area with white. Sometimes it seems that they are on the move.

New feet within my garden go –

New fingers stir the sod –

A Troubadour opon the Elm

Betrays the solitude.

New Children play opon the green –

New Weary sleep below –

And still the pensive Spring returns –

And still the punctual snow!

79 [poem number], 1859 [year of composition]

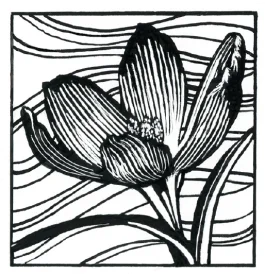

Crocus. Dickinson termed the crocus a “vassal” of the snow. A member of the iris family, the crocus has a cup-shaped flower. Tradition dedicates it to St. Valentine since it blooms near his holy day. The ‘Cloth of Gold’ crocus has been cultivated since the sixteenth century. Other early crocus species that Emily might have grown include the “tommies,” Crocus tommasinianus. Introduced into the nursery trade in the 1840s, tommies bloom pale to deep lilac with white throats.

Crocuses grow from corms, swollen underground stems crowned by a growing bud. Planted in autumn in well-drained soil, they repay the effort in early spring. The flowers stand up from the frozen ground like straight soldiers. Dickinson also dubbed them “martial.” After they bloom, they disappear, leaves and all.

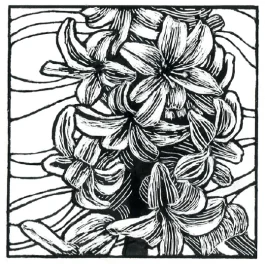

Hyacinth (Hyacinthus orientalis). Dense, fragrant hyacinths followed the crocuses. Dickinson remembered a glance from a friend “in Hyacinth time.” Gardeners often tell time by the bloom season rather than the calendar. In acknowledgment for a gift of bulbs, she wrote, “The Snow will guide the Hyacinths to where their Mates are sleeping, in Vinnie’s sainted Garden.” One wonders what conferred sainthood on Lavinia or, at minimum, canonized her garden beds. However, botanically speaking, Emily was accurate. Hyacinth bulbs are among the underground plant structures with contractile roots. That is, specialized roots pull the bulbs lower in the ground. Whether with a snowy guide or not, is subject to speculation.

Tulip (Tulipa). In another of Dickinson’s early poems, a sort of schoolgirl puzzle, she described a bulb as asleep and forgotten, save by the gardener. Since the flower in the poem wakes up dressed in carmine and the number of red-flowering spring bulbs is limited, a tulip is the likely subject:

She slept beneath a tree –

Remembered but by me.

I touched her Cradle mute –

She recognized the foot –

Put on her Carmine suit

And see!

15, 1858

Beyond plants of the bulbous tribe, another flower that carpets Emily’s garden is the pansy. One she grew was Viola tricolor, sometimes called Johnny-jump-ups as they pop up in unlikely places. They can also spread to the dinner table. As pansies are edible, they are lovely additions to salads and superb decorations for ice molds or cakes. When Emily baked gingerbread, she sometimes used them to decorate its shiny surface. Like many flowers of the season, they are diminutive.

A pansy is particular only about the weather. To one friend, Dickinson wrote, “That a pansy is transitive, is its only pang.” It will grow in cold weather, languish in hot. She gathered them into Spring bouquets and wrote this accompanying poem.

I’m the little “Heart’s Ease”!

I dont care for pouting skies!

If the Butterfly delay

Can I, therefore, stay away?

If the Coward Bumble Bee

In his chimney corner stay,

I, must resoluter be!

Who’ll apologize for me?

Dear – Old fashioned, little flower!

Eden is old fashioned, too!

Birds are antiquated fellows!

Heaven does not change her blue.

Nor will I, the little

Heart’s Ease –

Ever be induced to do!

167, 1860

The word “pansy” comes from the French word that means “to think.” Thus a pansy is pensive, with its flowers that look like faces, faces that invite contemplation. Perhaps that is why another nickname for this flower is “heart’s ease.”

As spring moves forward, the earth warms and more perennials emerge, shouldering buds up through the soil. One of the plants in the garden is the peony, masses of peonies. Austin and Susan’s daughter, Martha—called Mattie—later remembered “ribbons of peony hedges.” A twelve-year-old Emily once compared them to the young rosy face of the stable hand’s son. “Tell Vinnie I counted three peony noses, red as Sammie Matthews’s, just out of the ground.” (Peonies break the soil’s surface with pointed burgundy buds that bear a striking resemblance to noses.) Even in adolescence, Emily Dickinson could manage her metaphors. With the ground warming, the little bulbs spent, and the perennials coming into leaf, the stage is set for the peak Spring display.

With friends, Emily shared some of her spring’s abundance gathered from her garden or further afield. Once she sent pussywillow with an enclosure that read, “Nature’s buff message – left for you in Amherst. She had not time to call.” Native to wet sunny places in New England, the Upper Midwest, and southern Canada, the pussywillow, Salix discolor, is prized for its emerging, fuzzy catkins. It is an energetic small tree or large shrub, depending on one’s point of view.

Emily also enclosed pressed flowers in her letters. In a brief note to a fellow poet, she once sent bluebells. “Bluebell” is a common name that graces several plants, including a bulb, English bluebells (Hyacinthoides non-scripta), and a spring ephemeral, Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica). Because the letter is dated early April, it is likely the latter, since English bluebells bloom in Amherst later in spring. Virginia bluebells would have appealed to Dickinson, unfurling fluorescent blue-green leaves in March, nodding with blue clusters of blooms in April, sowing their seed and then disappearing by June. Like her poems, bluebells are startling and succinct.

As the days lengthened, Emily Dickinson took up her trowel, rising earlier, staying out later. She also took up her pen to celebrate the changing cadence.

A Light exists in Spring

Not present on the Year

At any other period –

When March is scarcely here

A Color stands abroad

On Solitary Fields

That Science cannot overtake

But Human Nature feels.

It waits opon the Lawn,

It shows the furthest Tree

Opon the furthest Slope you know

It almost speaks to you.

Then as Horizons step

Or Noons report away

Without the Formula of sound

It passes and we stay –

A quality of loss

Affecting our Content

As Trade had suddenly encroached Opon a Sacrament –

962, 1865

Early Spring is a season of watching. ❖

Reprinted with the permission of Timber Press from Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life, copyright © 2019 by Marta McDowell. All rights reserved.

Previous

Previous