Perhaps more than other occupations, gardening lends itself to philosophizing. Knitters, I suppose, can make something of dropped stitches; or cooks can conjure shattering associations with a fallen soufflé. But gardeners (particularly garden writers) will contemplate the seasons, see the world in a tiny flower, or—given any chance—grandly reflect on birth and death in the rhythms of nature!

Hence:

Autumn, as we all know, is the season of senescence, the time of the dying year, the pause before the icy stillness of Winter. We rake dead fallen leaves; we cut down browning perennials; we pull up frost-fallen annuals. We can, and do, promise ourselves a resurrection by planting Spring bulbs and making next year’s compost from the raked leaves. But in all honesty we are going to go through a lot before that happens.

Aging of gardens—and of people—is something our culture would prefer not to think about. These days I have trouble finding Spring bulbs for sale in local nurseries. My nearby nursery simply doesn’t sell Spring bulbs: They tell me to go online to get them. More popular in the store are artificial Christmas snowflakes and the like. There are poinsettias, which will be tossed out after the holidays, and (sometimes) paperwhites for forcing—also to be tossed out after doing their thing. It is as if Winter is best ignored and planning for next Spring is not “living in the moment,” as we oldies are urged to do.

In the past, if you were lucky enough to achieve it, old age was not the embarrassment it now seems to be. Thomas Jefferson famously, and proudly, said he was “an old man” but “a young gardener.” Of course he had an advantage over people like me—he had muscular help in his garden. I can’t claim to be “a young gardener”—at least not in actuality—because I simply can’t do what I once did. For example, I am not doing much leaf-raking these days. I rely instead on a nice young neighbor with a leaf blower.

Traditionally, great gardeners were not young and indeed were often respected for their longetivity. Some attribute this to a combination of serenity and exercise. Shakespeare noted in Hamlet that “There is no ancient gentleman but gardeners, ditchers and grave-makers.” Certainly there would be plenty of opportunity for exercise and contemplation in these professions! Anyway, for whatever actual reasons, many gardeners did live to be very old: Robert Louis Stevenson described his gardener as “old and serious, brown and big.” Le Notre (Versailles) was about 90 when he died; Mr. George Russell (famed for his lupines) was 93; Darwin’s gardener (“Old Lakeman”) died aged 96.

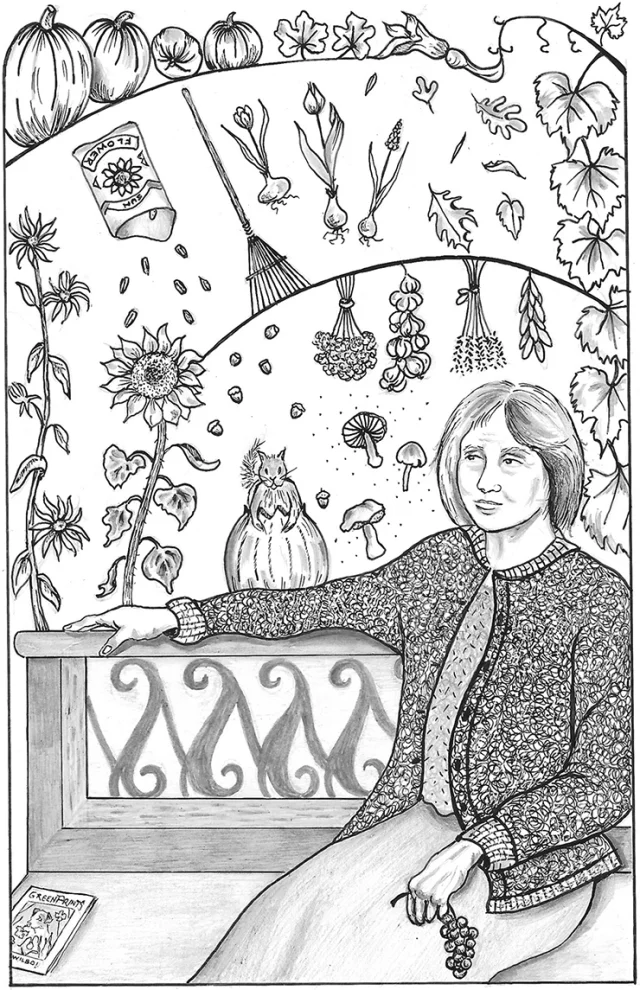

Our culture, uneasy with aging, often strives to alleviate the condition with jolly cruises and a bit of Botox here and there. Rarely is recommended the ploy of leaning on a shovel and . . . well, just that. There’s nothing nicer on a crisp Autumn day then leaning on a shovel—or propping it up and sitting on a garden seat, perhaps to think about the garden year that is winding down. Some things were disappointing. Some things surprised us with unexpected results—maybe a forgotten plant came unexpectedly to life. Perhaps that packet of seeds we sprinkled somewhere suddenly, magically, filled a space with color. Some things didn’t work out as planned, and we just had to put up with it.

Sitting in the Autumn sunshine, it’s not hard to compare the life of the garden with the life of the aging gardener, especially (sorry) for a garden writer! So I do, and so I shall.

But lest I’d be judged as narrow-minded, let me also give a passing thought to our nongardening friends. May your knitted scarves be flawless, you soufflés rise to perfection, and your lives be long and fruitful.

And may we all celebrate next Spring together! ❖

Previous

Previous