I am a Southern organic gardener on the Louisiana Gulf Coast, near New Orleans. We plant early here, knowing that by mid-July, our tomato plants become shriveled, yellowing, bug-chewed masses of vines with little more to show for themselves. I started in mid-March, with successive plantings throughout the garden in April and May. By late May, my March tomato vines were seven feet tall and brimming with ripening fruit. By early June, the first crop had already been harvested with many more coming in to take their place.

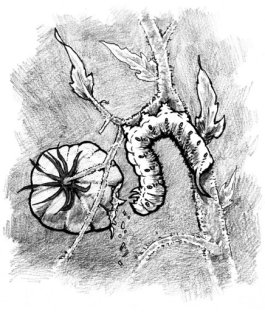

Then: the onslaught. Like a barbarian horde had appeared overnight, my plants were suddenly overwhelmed by Manduca quinquemaculata, better known as the—dreaded—tomato hornworm, just a few of which can strip a seven-foot-tall vine bare in two days. Flourishing basil and fresh mozzarella were ready for the next crop to join them on the plate. Neighbors were clamoring for handouts of juicy goodness. The onslaught had to be stopped—now. I immediately plucked those I could find off of the vines, snipped them in two with my garden shears, and tossed the gooey, green remains into the storm drain.

I didn’t give much thought as to where these creatures came from or where they ended up if I didn’t decimate them. All my efforts were focused on eradication. I did examine them, though, and found that they weren’t really ugly, but rather a bit clownish. In fact, they were cute (kind of), with their chartreuse coats, twirly faux-horn on rump, puppy-like false eyes, and six little paw-like forearms (if you can call them that). Yet I didn’t feel even a brief twinge of “Sorry, little guy,” when I sliced them in two with my shears. They were after my tomatoes!

After a couple of days of search and destroy—literally plunging my head and arms into my vines to follow the trails of caterpillar poop—I sprayed all the vines with the organic bug killer spinosad. I was careful to get under the leaves where they sometimes hide.

That’s when I noticed something even more menacing and insidious: the (also-dreaded) tomato fruit worm. Yes, many—if not most—of my green, pink, and red fruits were almost inconspicuously drilled, chewed, and pooped in: ruined. And when I’d find a plump tomato that looked unscathed, I’d reach for it and grab a gross, soupy, slime of oozing juice and caterpillar crap, sometimes with the caterpillar entwined in my fingers. This was followed by another blitzkrieg of spinosad. Finally, the biological warfare got things under control. The hornworms disappeared and the fruit worms lessened.

As it turns out, hornworms change into one of the most beautiful and graceful creatures of the insect kingdom: hawk moths. Hornworms, once satiated and after checking their calendars, descend the vines into the ground, make little hard-shell cases around themselves and quietly transform. Once they emerge from their safe little shells in the ground, they are birdlike creatures, more so than any butterfly. They flit around and hover over nectar-rich flowers, extending their long proboscises to sip a sweet meal. Their only other interest is finding a mate. They are big bugs with fat colorful bodies supported by large and powerful wings. And quite unbug-like: they appear and even feel a bit feathery.

Yet butterflies like the monarch or swallowtail get all the love. People rush out in Spring to buy up the gallon containers of milkweed at garden centers so they can actually nurture monarch caterpillars along to winged glory. Not so the moth. Perhaps it’s because they tend to be creatures of the night, with a certain nocturnal creepiness made worse by movies like Silence of The Lambs and The Mothman Prophecies.

And now for my dilemma. I am one of many who thinks that killing a child, human or animal, seems generally more egregious than killing an adult. But I had no such moral dilemma in

squashing, slicing, or drowning these young caterpillars (who had no such qualms ending the lives of my tomato plants). I had no remorse at all—until I found a hawk moth in waning daylight resting on a brick wall of my house within inches of my rescued tomatoes. I realized at least one hornworm must have escaped my warfare and become what Nature intended: a beautiful hawk moth, quietly resting before taking its dusk flight in search of nectar and a mate. Or was she done mating? Had she already laid her tiny, inconspicuous, pearl-like eggs on the undersides of my tomato vines? Was she about to?

I didn’t take any chances. I grabbed a can of bug spray used primarily for mosquitoes on the deck (betraying my own pledge to never use chemical insecticides in the garden) and let her have it—with blast after blast of spray.

I felt an immediate wave of remorse for what I had done, even if it had been for the greater good of my tomatoes.

And then came my rationalizations: If it wasn’t for that blasted moth, there wouldn’t be any hornworms to kill. I had spared future caterpillars from getting killed by me by making sure they’d never be born. Besides, I hadn’t actually used a chemical pesticide in the garden—only near the garden—which doesn’t count. My rationalizations were turning into absurd mind theater.

My regret grew when I watched the moth fall from the wall and struggle across the grass, frantic at first but slowing. I hoped it would die a quick death but, perhaps because of its size, it didn’t. I felt as though I had sprayed a tiny bird with insecticide. This thought hurt. I even thought of grabbing the poor thing and washing it off with the hose—but quickly dismissed that as lunacy: the damage was already done. I could kill the children. But the beautiful, graceful adult proved far more emotionally complex for me. And this for a moth whose offspring do great harm to my garden!

In the morning, I woke, and as I always do before leaving for work, checked the tomatoes for harvestable ones, critter damage, etc. I knew where the moth lay, about eight feet from the garden in the grass. I didn’t want to look. But I just had to see the aftermath of what I had done. Surely I’d find her dead as a doornail and that would be that. No such luck. A splayed wing twitched. I hoped it was just from the breeze I felt on my neck. I looked closer. Legs twitched as well, below the tops of the grass blades, where the wind could not find them. My heart sank, I knew I had to do what I should have done the evening before: squash her. I felt like I did when I took my beloved Max, a black lab of many years, to the vet to be euthanized after his terrible bout of bone cancer. Only this time I was the cause of all this misery.

This experience has changed me, unlike any other gardening experience, good or bad. I don’t think I did a terrible thing or even a bad thing, but I don’t really know. All I know is that I feel awful for doing it. By early July, my later successive plantings were brimming with green fruit showing the slightest hints of blush. No sign yet of more insect pests.

But what should I do the next time they come? What if next year I grow some extra tomato plants away from my garden crop—and move any insect pests—excuse me, those whom nature calls to the table—to there? ❖

Previous

Previous

This article has been updated to remove an overtly political statement and judgment. GreenPrints doesn’t promote any political agenda. This article has also been updated to remove erroneous scientific references about what type of moth tomato hornworms become. We regret these errors. Bill Dugan, Editor & Publisher