Read by Matilda Longbottom

The attic bedroom of our old farmhouse is where we hide magic: the tiny Christmas trees that appeared by the beds on Christmas morning; the tiny cannabis plants, years later, hidden in the same place (but this time from me); the Venus Fly Trap, for my youngest’s tenth birthday.

Our ancestors may have understood the miracle of the Christmas tree, with its ability to retain leaves through scorching heat and freezing cold, better than we, who see them piled up outside the December supermarket then whisk them home to our cozy rooms. If the magic of Christmas trees might need to be explained, and the magic of cannabis plants needs to be avoided, the Venus Fly Trap proves that the magic we seek is not always the magic we get.

The Fly Trap, as Joseph Paxton said in his Botanical Dictionary of 1840, is “a very singular little plant.” No wonder it captured the imagination of the 18th century world when first “discovered.” No wonder that my little son wanted one more than anything. When I saw one, six weeks before his birthday, I bought it at once and hid it.

So our own Dionaea Muscipula was hidden in the attic window, where the autumn flies, wafted upwards by the rising heat in the house, would congregate. Its leaves grew pink as Aurora’s blush, it drank copiously of the distilled water, reserved generally for the steam iron, and by the time the birthday came, it was a pretty thing indeed. It was greeted with excitement and awe. It was his “best” present. There it sat, amongst the ribbon and wrapping paper, spent candles and crumbs. Some of the leaves, with their expectant cleavage, were seductively open; others, like tight little purses, were successfully digesting the attic flies.

William Bartram, in his Travels, called the Dionaea “gay and sportive vegetables,” and ours, on the birthday table, was no exception. Apart from being no ordinary plant, it had become endowed with the love of a ten-year old and the memory of a special birthday. Could we, as Bartram said, “after viewing this object, hesitate a moment to confess, that vegetable beings are endued with some sensible faculties or attributes, familiar to those that dignify animal nature?” In other words, it had become a member of the family, as much part of it as the battered teddy, or the sleepy cat. Like them, it might be loved by all, but it was left to me to see that it continued to thrive.

I knew that, as autumn progressed, things were not going to be as easy with this daughter of beauty, this lover of flies. I read carefully how to tend its wants: It must never dry out; it liked live insects. The first was easy; the second a problem.

Anthony Huxley, in Plant And Planet, explains how the Fly Trap works. As I understood it, the mechanism of the hinges is caused by the sudden taking up or losing of water by cells along a central axis. The real miracle, though, is the plant’s apparent ability to distinguish between an insect landing on the leaf, a drop of rain, or an inert object such as a pencil. Dionaea can not be fooled even by the bouncing tip of a paintbrush.

“Admirable are the properties of the extraordinary Dionaea Muscipula!‘ wrote William Bartram. His father, John, was probably one of the first Americans to see the plant in its native habitat, an area of about 50 square miles near Hamilton, North Carolina. It was William Young, though, not the great John Bartram, who took credit in London for this extraordinary find.

William Young seems to have been a bit of an opportunist. How different he seems from John Bartram who, on resting from ploughing and examining a daisy, so we are told, decided in a flash of insight to give the rest of his life to the study of plants. A contemporary called Young “fine and fashionable with his hair curled and tied in a black bag,” and one can picture his showing off the wonders of his Fly Trap. I prefer to think of the Bartrams, William and John, slogging through marshes, through perils and hardships, crouched in their breeches over these strange, sinister little plants, and asking, as William does, “Is it sense or instinct that influences their actions? It must be some impulse; or does the hand of the Almighty act and perform this work in our sight?”

Once introduced to Europe, the Fly Trap seems to have survived there. When one reads about its culture, that’s not surprising: It sounds simple enough. It likes boggy, acid soil and compensates for the lack of nitrogen in such earth by capturing and digesting insects. The soil should not be fertilized, then, and—in our times—it’s best to use distilled water, since tap water can contaminate it. So far, so good. I read, too, that when no insects were available, it would digest “proteinaceous material” such as a small piece of meat or cheese.

As the mother of six sons, I am used to appetites, and worry if food is not devoured voraciously. After the last October fly had died its sleepy death, I figured that Dionaea must be getting hungry. My first idea was to feed her some of the dead flies which had collected on the attic windowsill, unable to escape outside. So, after breakfast one morning, when everyone had left for school, I bustled in cheerfully with a fly held in a pair of tweezers. I jumped it up and down a bit on the open leaves, waiting for the trap to snap. But Dionaea was unmoved. Maybe, I thought, she needed privacy? I balanced the fly on the cleavage, and tiptoed off, but when I crept back later, no fat little well-fed purse greeted me. Perhaps the mistake had been to offer a dead fly. A good friend of ours who had refused Thanksgiving Dinner at her parents’ home on the grounds that she does not “eat dead animals” was upset by her father’s reply that “We don’t eat live ones.” Maybe it was some complication like that?

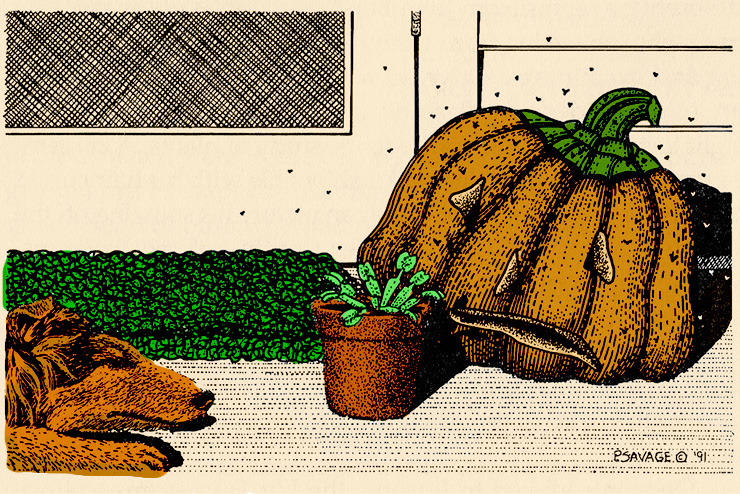

About this time, the Halloween pumpkins had begun to rot, and we were having an unusual warm spell. It was not warm enough to reintroduce flies into the house, but the pumpkins outside were swarming with fruit flies. I rejoiced.

One really warm midday, I took her out, pot, water saucer, and all, and put her right next to the biggest, squishiest pumpkin. A cloud of flies rose at my arrival, and I set her down, sternly admonishing the dog to keep away. The dog seemed puzzled, but the flies seemed properly attracted, and soon swarmed all over the open, hungry leaves.

Maybe they were too light. Maybe it was not warm enough. Maybe she simply did not like them. The leaves were still open, waiting, when I brought her in at dusk. I sustained a good deal of teasing for “taking a plant out to lunch,” but no one seemed able to solve the problem. We tried hamburger, and raw liver, with no response. I wondered if our Dionaea, with so many “with-it” teens around, had perhaps decided to become a vegetarian, too. I tried a little of my niece’s tofu, a bit of my son’s grilling cheese. Pale now, all leaves open and none filled, she still was not tempted. I began to worry about the garbage piling up in the pot. Maybe, like the teenagers, she could eat nothing and live in filth? I decided I would pretend not to worry.

Alice Coates, in her Book of Flowers, points out that Dionaea must not be “ecologically successful” as they are so rare. In nature, they are confined to an area around Wilmington, North Carolina, in what Randall Schwartz says is “thought to be an ancient meteor crater,” now filled by a bog. When first introduced to England, it was not universally accepted that they were, in fact, carnivorous. John Ellis, Fellow of the Royal Society of London, did not believe it, and he sent one to his friend, Linnaeus, who evidently was not convinced, either (but apparently only had a dried specimen with which to judge). Darwin finally experimented, and concluded that Dionaea was carnivorous, calling it “one of the most wonderful plants in the world.” I wish I could find how he got it to eat in front of him!

In spite of everything, I am not, I confess, absolutely convinced myself—at least not about our own particular pet. I am beginning to wonder if it is trying to say something to me about the nature of its desires. (It seems, evolutionarily, to be a creature of the highest intelligence.)

I’m not sure. I will wait a while to see if Spring does its business, if new green traps will replace the blackened stubs that refused all my offerings. That, of course, would be miracle enough. But, if not, I’m going to try another tactic: I’m going to hit the fertilizer bottle, and, if that doesn’t work, I shall try the one weapon that never fails in my family: ice cream. ❖

Previous

Previous