Read by Matilda Longbottom

One November, a red lumpy sphere mysteriously appeared on the cold marble table. There it sat for days on end—admired, silent, proud, waiting. At night it reflected light from the fireplace, its thick, hard shell slowly beginning to crack and split. By day, it stood alone, dark red, cool to the touch.

One day passed white as another—brief, cold, and clear. I’d come in the back after hours of sledding and begin a frantic shedding dance. Mittens, hat, scarf, jacket, sweater, and boots were all thrown into a heap of damp wool and ice crystals, crystals that melted into a puddle of salty gray slush on the floor.

Barefoot and numb, I’d run to the dining room and drape my icy woolen socks over the fire screen. My toes were bluish-white; my fingers, thin blades of ice. I’d rotate my position every few seconds—first, warming my front until my kneecaps steamed, then heating my back until my spine tingled and I caught the unmistakable whiff of singed wool on my rear.

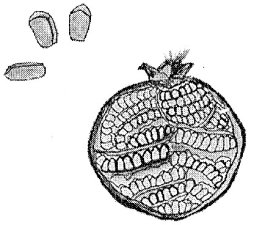

It was with my back to the fire, hands clasped behind me, that I first eyed the squarish nature of the sphere, for that’s how it appeared—not exactly round, but with smooth planes that merged into a globe. A miniature six-pointed crown graced one end, from which fragile pale yellow tufts emerged. I didn’t know what to make of this oddity, but I sensed it was within my mother’s domain—her winter toy to do with as she pleased. I stood there for some time, absorbing heat from the fire and the sun, whose last rays of warmth angled through the window panes.

Then on a stark winter day with deep drifts piled high outside the door, the driveway ice salted and sanded, and long, thin icicles dripping small caverns into the crusted snow below, without any warning, my mother reached for her old, bone-handled knife, sharp as a razor. She steadied the red lump before her and drove the knife in. With several awkward cuts, she pried it apart. A quick pool of juice seeped into the cutting board and trickled onto her lap. Lost in untouchable thoughts, she did not seem to care. Then suddenly, she looked up with a bright smile on her face and announced, “This pomegranate must last till Christmas!”

Before us lay a maze of awkward shapes, much like a broken wasp’s nest. Glistening rubies bounced upon the table, each one a small pentagon wrapped in moisture. Digging out the tart kernels with our sooty fingers was a chore, separating them from their bitter white tissue-paper housing even worse.

Once I’d had my first taste, though, I wanted only to call the fruit my own—to relish it alone and completely. Always, some parts were sweeter than others. Always, I wished to devour all 500 seeds in one huge mouthful, but pomegranates were expensive, and we had only one to last the entire season. I resigned myself to savoring a few morsels each night after dinner. In this way, the pomegranate became my friend. And it remained fresh for weeks, naturally cold on the cool marble table.

We lived around this table, for it was in front of the fireplace that roared crimson every night. Following the holidays, the table hosted heaps of navel orange and tangerine peels, still fragrant and moist; a blizzard of cracked pecans, chestnuts, and walnuts; silver nutcrackers and picks; long-forgotten cups of tea—cold and skimmed with soured cream; crumbly sugar cookies; menacing squares of fruit cake emitting evil vapors; tarnished candlesticks coated with drippings; crumpled red napkins and ribbons; huge crystal ashtrays overflowing with spent matches and butts—most bearing my mother’s lipstick signature; half-eaten squares of questionable chocolates; sweetly fragrant apple cores, browned and rotting; rejected ellipses of ribbon candy; and countless other holiday tokens all delicately coated with long silken hairs from our haughty French tortoiseshell Persian. My mother enjoyed the table’s chaos and joked to her friends that this was her wintertime indoor compost pile.

In the center of this disaster stood the proud red garnet, still laden with plenty of faceted jewels—each one throbbing, beckoning, mocking: Eat me slowly, make me last, or I’m gone.

I thought my mother should have bought more; but she was a depression orphan and considered pomegranates, and many other fruits, in the exotic and expensive category. The thrill of the season was finding two or three small tangerines in the foot of one’s Christmas stocking, along with a few clunky walnuts and Brazils in their impossible shells. The only fruit we ate in quantity were small tart Macintosh apples from the local orchards. We kept them in round bushel baskets on the back stoop, and I thought nothing of eating five or six in a row, usually right before dinner.

Dinner was a late affair in winter, for my father’s train was often delayed by an ice storm or blizzard. While waiting for him to come home, I’d start my homework by the fire, one eye in a book and the other on the pomegranate. As the clock approached eleven on those long, blustery nights, my parents would pour themselves petite glasses of dry sherry and the three of us would sink into the lumpy down-stuffed chairs by the fire. They’d offer me a sip, throw a blanket across my lap, and together we’d review the day and slowly pick apart the pomegranate.

Now that I live out West, I often think about our holiday ritual of 30 years ago. Where I live, pomegranate bushes are as common as forsythia back East. If left on the bush too long, the fruit cracks open like a rough and jagged canyon, revealing its treasures for nuthatches, jays, blackbirds, and sparrows.

Many folks here would never swallow the seeds and wince when you say you do. Instead, they squeeze out the juice to make pomegranate jelly. At my first pomegranate squeezing party last fall, as the guests squeezed, pressed and juiced, I stood back and savagely ate one, two, three, four, then five, six, seven huge red fruit. I followed that with wine, cheese, bread, crackers, and a rich bean soup from Heaven. I went home satiated, fell ill several hours later, but still mused to myself, “Oh, it was never this good back East.” As much as I long for the northeastern woods with low stone walls that lead to nowhere, they don’t grow pomegranates, and that one fact makes the West livable.

When my husband discovered my passion, he began to bring numerous pomegranates home. Every one had its history: “These are from Blanche Nosworthy’s bush, and these really big ones are from Sharon and Kevin’s—they’re whiter, but sweeter.”

Last year, a drunk driver rammed his mother’s favorite bush; we mourned our losses, but the bush fooled us all and grew back healthier than ever. When friends move, we take it personally: “Uh-oh, no more access to their bushes.” And when I fed the neighbors’ horses last summer, I eyed their bushes and wondered aloud, “Do they eat them or let them fall to the ground?”

Ever the gardener, my husband ambitiously planted not one or two, but 20 volunteer pomegranate bushes from as many sources as possible. When they began to bear fruit after only one season, I was shocked. I thought the bushes would have to be very old to produce such wonders.

Now, from Thanksgiving through winter, we sit on the broad wooden steps of our farmhouse and sample fruit. Some seeds are pale pink and sweet like sugar water, but lacking in flavor. Others are so tart your mouth puckers. The challenge is to find the perfect combination of tartness, sweetness, and deep rich flavor.

My husband taught me the correct way to crack them open. Find the natural split, follow its line, apply pressure, and pull apart slowly until huge chunks of glistening rubies reveal themselves—naturally separated from their parchment housing.

When a seed falls to the steps, I pick it up and eat it. Dog hair, horse manure, compost scraps, foxtails, cat litter, work shoes, moldy leaves, dead buds, and all manner of things considered nasty fall on those steps, but don’t care. I brush off the morsel and pop it in my mouth. Gold shouldn’t be wasted.

Surrounded by baskets toppling over with pomegranates, I am excited and ready to share my treasures, but my father is gone. Though I imagined his death would be dramatic—a derailed train in a terrifying blizzard—the New York commuter rail never failed him. He was old and ill, and it was simply his time.

My mother now lives in a tiny room in a big, white Colonial house atop a wooded hill in Connecticut. Though her mind is wobbly, her body is strong and her wit intact. So each November, I send her a pomegranate with a note that says, “From our garden.” I know she takes great pride in that fact, as though it were my first valentine or little poem. And I know she splits it apart with a bone-handled knife, sharp as a razor, and sets it atop her little bureau to last all winter. ❖

This article was published originally in 1999, in GreenPrints Issue #40.

Previous

Previous

That is such a sweet and timely story for the holiday season. It reminds me of my childhood, we didn’t have much money and truly treasured little treats like this.