No Winter lasts forever; no Spring skips its turn. – Hal Borland

Winter isn’t the season for everyone. “I shudder at the approach of Winter,” wrote Thomas Jefferson from his mountaintop in (cold) Virginia to John Adams in (colder) Massachusetts. “Winter is icummen in,” wrote poet Ezra Pound (Idaho). “Lhude sing Goddamm.”

“Winter is coming,” as all Game of Thrones fans know, is a sinister threat. It means that you may be fine and dandy today, but don’t let down your guard—all hell may break loose tomorrow which, in the Game of Thrones universe, means not just a spot of nasty weather, but slaughter and mean dragons. There’s a kinder quote from the Greek poet Hesiod, who wrote, “It will not always be Summer; build barns.”

The bottom line, though, from all of the above, is pretty much the same thing.

Brace yourself. It’s about to get cold.

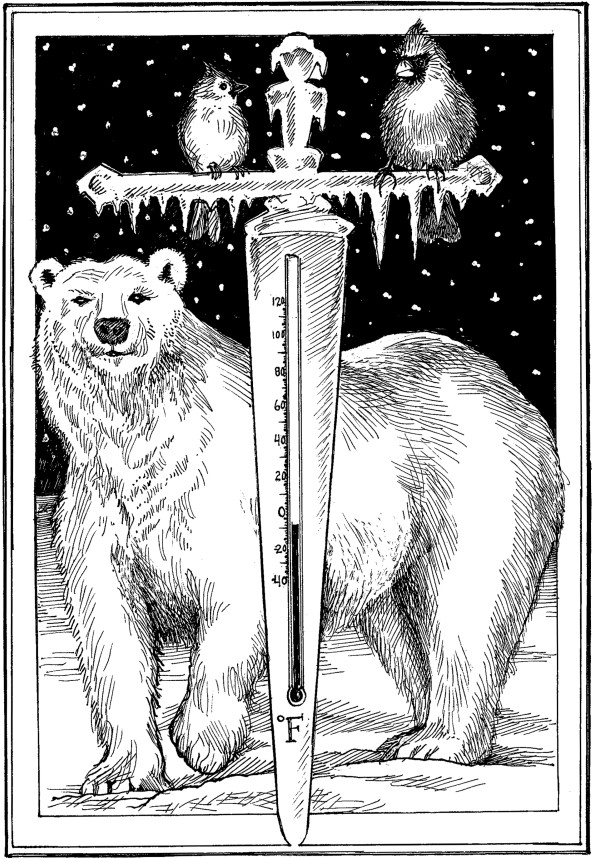

Here in Vermont that can mean really cold. Where we live, with a little help from wind chill straight from the North Pole, Winter temperatures occasionally hit -20°F or worse. That’s the sort of weather that sends the cats under the couch, causes people to fight over the chair closest to the woodstove, and makes us think twice about going out to get the mail.

Theoretically, cold shouldn’t be a problem for us. As mammals, we’re warm-blooded animals, basically all chugging little biological engines pumping out heat at the rate of 50 kilocalories per hour per square meter of body surface. What this means is that if we were completely insulated—say, sealed up in plastic bags—we’d literally cook ourselves to death. Luckily we aren’t: we steadily get rid of all that heat via radiation—we lose a lot of it from the tops of our heads—and through the evaporation of water through our two million sweat glands.

Still, like a bunch of bubbling teakettles, we’re continually making heat. Each of us, from head to toe, is encased in a cozy personal bubble of warm air. This is a layer about six millimeters thick, constantly in motion as air closest to the body’s surface warms and rises to be replaced by cooler air from our surroundings. The problem is that this toasty warming effect can only go so far. When the surroundings are a lot chillier than we are, warm blood or not, we get cold.

Nature has a lot of ways for coping with cold—but basically, for a lot of us, it’s all about air. Fur, for example, traps that layer of warm surface air, keeping it safely close to the skin. The thicker the fur, the more effective it is as insulation: polar bears, for example, are so well insulated that they’re invisible to night-vision goggles, which zoom in on radiated heat.

Ditto for feathers: When birds fluff their feathers in chilly weather, they’re trying to trap the maximum amount of insulating air. People in cold climates would be better off furry, but they do their best with clothes. Clothing, in uncongenial climates—whether from Armani, Calvin Klein, Walmart, or Tractor Supply—exists to trap air. The insulating value of clothing is measured in units of Clo, in which 0 Clo means stark naked and 1 Clo is the amount of insulation required to keep a relatively sedentary person— think your average couch potato—comfortable at room temperature. (The Clo scale was established in the pre-feminist 1940s; therefore the 1-Clo standard of comfort was originally defined as a three-piece businessman’s suit and a set of BVDs.)

In keeping warm, the secret to effective insulation is layering, in which multiple layers of clothing trap multiple layers of air. (Best, says The Washington Post, is three layers, starting with a set of polyester long johns.) Experts in the matter of Clo are the northern indigenous Inuit, whose parkas, pants, boots, and mittens add up to 4.0 Clo, almost as good as the insulating value of the average sled dog’s fur coat (4.1 Clo), though not a patch on that of the average polar bear (8.0 Clo). Clo is the reason gardeners in cold climates wrap sensitive shrubs in burlap in November.

So what about plants?

Some garden plants, faced with Winter, simply turn up their toes and die. Lettuce, tomatoes, beans, cucumbers—all annuals, from the Latin annus, year—give up the ghost at the end of the growing season, leaving their remains to the compost pile. The killer, when it comes to annuals, is ice, which is why many garden plants bite the dust after the first hard frost. When water inside cells freezes, the resultant spiky ice crystals can tear them apart from the inside out; and ice in the matrix outside cells can be just as bad, pulling internal water out through cell walls, leaving behind desiccated husks. The blackened, wilted remains of frost-bitten gardens are the aftermath of cells losing a battle with ice.

Other plants know how to hunker down. Perennials such as asparagus and rhubarb, for example, come back year after year. (Our asparagus has led a somewhat pampered life, but the rhubarb is a rugged survivor, having outlasted at least two seasons of being inadvertently mowed down with the tractor.) Chives and horseradish come up time and again; so do daffodils, tulips, crocuses, irises, and lilies. Each year their vulnerable tops die off, but all have back-up storage organs—bulbs, rhizomes, roots—safely sequestered underground. If perennials were people, they’d have stockpiles of tunafish and bomb shelters.

Deciduous trees and shrubs cope with cold by going dormant—the botanical equivalent of hibernation, in which bears, squirrels, skunks, and bats take one look at the weather, then curl up for a few months and go to sleep. In dormancy, metabolism slows down to a sputter; Winter trees survive the season because they’re pretty much out of it

During this dozy state, they’re also protected by the arboreal version of antifreeze—sugars and proteins that lower the freezing point of water and fend off ice damage. Maple sap—which, boiled down, turns into maple syrup—is sweet because it functions in the Winter tree as antifreeze.

Personally, having been raised with it, I like Winter—though I can see the downside. In Star Wars, the perpetually cold ice planet Hoth was fearsomely unpleasant; and Narnia, in the grip of the White Witch, was miserable in a state of always Winter, but never Christmas. We wouldn’t want to have Winter all the time.

Still, as Anne Bradstreet wrote, while somehow managing to write poetry and to raise eight children in the 17th-century Massachusetts Bay Colony: “If we had no Winter, the Spring would not be so pleasant: if we did not sometimes taste of adversity, prosperity would not be so welcome.”

And if our gardens didn’t sometimes vanish under snow, it wouldn’t seem such a miracle to watch them once again turn green. ❖

Previous

Previous