In the two years I took to write my book, 100 Birds and How They Got Their Names (Algonquin Press), I had ample opportunity to think about differences between birders and gardeners, and the people in between who love both their gardens and the birds that visit them.

Most of us know and are often somewhat intimidated by a real birder who gets up at dawn to make lists and can confidently identify the dozens of those little brown birds that look much the same to the rest of us. What was I doing writing a book about birds, I repeatedly asked myself. Was it a task for a garden writer? It’s easy to find the names of flowers: They stay still and wait for you to identify them. Birds never stay still long enough for me to match them with their pictures in my bird books.

Just because I am a gardener, however, I already loved birds and wanted them in my garden. And as I studied them more, I came to realize that even if I was poor at naming them, I could provide a good place for them to live and thrive. Indeed, birds, and birders, need gardeners.

True, not all birds are always welcome in our gardens. They can cause a lot of damage as well as enchanting us. “I value my garden more for being full of blackbirds than cherries,” wrote Joseph Addison in 1712, “and very frankly give them fruit for their songs.” A nice sentiment, but not easy to remember when all the new peas have been eaten overnight. It’s hard to control birds—nets are a bother, scarecrows don’t really scare crows, and inflatable owls and snakes don’t work for very long. Birds are smart—they have to be to survive—and they need to eat constantly, so gardeners aren’t going to love them all the time.

But a garden without birds? Unthinkable. A cherry tree in bloom needs a robin singing in its branches or its statement is half made. Not to mention that birds “will help you cleanse your trees of Caterpillars, and all noysome worms and flyes,” as William Lawson said in his 1618 book, A New Orchard and Garden. (He also said that he had lost “whole Trees” of fruit from birds eating the buds and suggested shooting them with a musket, or chasing them with a tame sparrow hawk. Still he concluded that he would “rather want their company than my fruit.”)

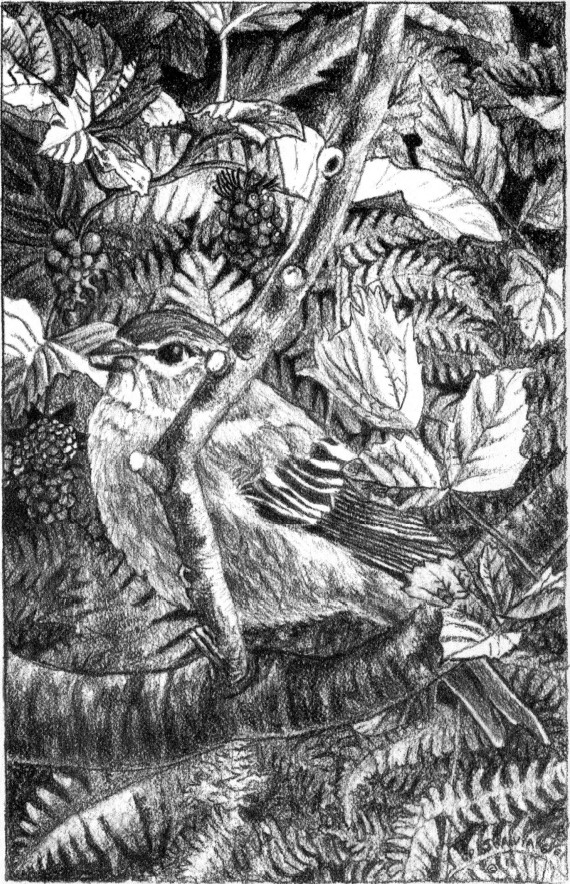

Nowadays, although we enjoy growing fruit and vegetables, most of us aren’t dependent on our own produce. We can afford to make our gardens places of refuge and relaxation, which surely include the presence of birds. But birds can’t be brought to our gardens and planted there—they have to want to visit. And they often favor an environment that distresses tidy gardeners. Songbirds need untidy brush for shelter. Woodpeckers and flickers live where there are dead trees and branches. Mowed lawns satisfy few birds, especially if the grubs have been killed with insecticides. A puddle in the driveway may look untidy, but it provides water for bathing and drinking. Indeed, we may sometimes have to be “worse” gardeners if we want birds around.

For myself, I learned about my garden as well as about birds when writing my book. Nowadays, I never (well, almost never) bug my husband to have the driveway patched. I never (almost never) fret about tangles of weedy brush, or trees that need pruning. Although I’m still far from an expert on birds, at least I know I can provide a good place for them to live—and even if I can’t identify every bird in my garden, I can appreciate the miracle of its presence.

In the Sixth Book of The Aeneid, Virgil wrote, “The descent into Hell is easy” (“Facilis descensus Averno”). The word for hell, “Averno,” means “a place without birds,” from the Greek a, “without,” and ornis, “bird.” Avernus, the entrance to hell, was a toxic Italian lake, the fumes from which were said to kill all birds.

A place without birds would be a kind of hell. We need birds. And we need to help and know them as much as possible. ❖

Previous

Previous