Read by Matilda Longbottom

Name a famous squirrel.

Go on, try.

And just for an extra challenge, make it a real-life squirrel.

Which rules out Beatrix Potter’s (obnoxious) Squirrel Nutkin; C.S. Lewis’s (gallant) Pattertwig; and Scrat, the hyperactive saber-toothed squirrel of the movie Ice Age (2002). Also, Melanie Watts’ Scaredy Squirrel, the terrified hero of a picture-book series, who cringes in his tree primed with everything from Band-Aids to a parachute, preparing to deal with Martians, sharks, poison ivy, and killer bees; and Kate DiCamillo’s Ulysses, a squirrel who—after a near-disastrous encounter with a vacuum cleaner—develops superpowers.

Fictional squirrels aren’t hard to find. Famous actual squirrels, on the other hand, are scarce on the ground.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, squirrels were popular pets, paraded by the wealthy on gold-chain leashes and housed in tin-lined cages with running wheels. Or allowed, not always successfully, to run loose around the house: Georgianna Shipley’s Mungo, done in by a dog in 1772, was immortalized in a eulogy by no less than Benjamin Franklin (“Alas! Poor Mungo!”). Franklin offered, in a kindly P.S., to send her another squirrel.

Presidents Warren Harding and Harry Truman both had pet squirrels—both named Pete—and among Teddy Roosevelt’s multitudinous pets, which included a badger named Josiah and a bear named Jonathan Edwards, was a flying squirrel that came to meals riding in various Roosevelt children’s pockets.

More recently we’ve had the Banff Crasher Squirrel, who showed up in 2009 in a camping couple’s selfie and became a viral meme on social media—eventually sharing pictures with the Beatles, JFK, Abe Lincoln, Neil Armstrong (on the moon), and George Washington (crossing the Delaware). For a while there was even a Squirrelizer website that allowed you to add the Crasher Squirrel to your own home photos.

Equally famous was the Purple Squirrel, captured in a backyard in Jersey Shore, Pennsylvania in 2012. No one ever figured out just why the squirrel was purple, but before he was released back into the wild, he became an internet sensation, acquired a personal Facebook page, and inspired a country-music song entitled “Thor, the Purple Squirrel from the Jersey Shore.”

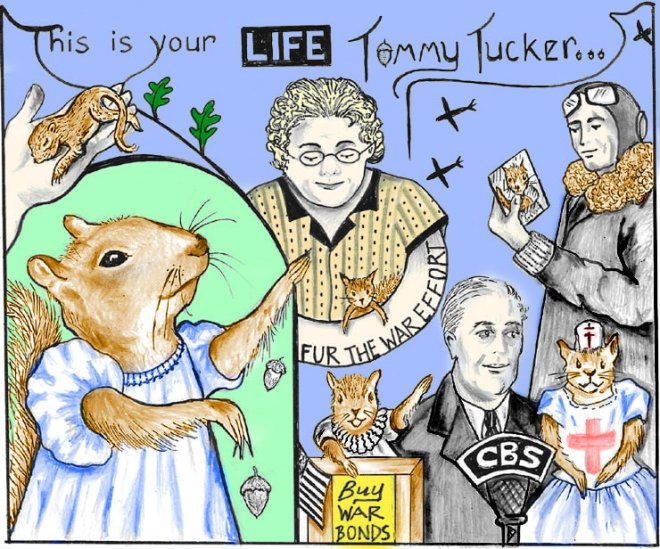

If you’d been around in the 1940s, however, you would have known at least one squirrel by name. Tommy Tucker, a male gray squirrel, was adopted in 1942 as an infant—a stage known to squirrel experts as a kitten—by Zaidee Bullis of Washington, DC. Zaidee made Tommy a Bullis family pet, providing him with a tiny bed, a room full of miniature toys, and a vast wardrobe of all-female clothes, since it was impossible to fit Tommy’s bushy tail into pants. During the war years, Tommy skyrocketed to fame, touring schools and military hospitals (decked out, for the latter, in a squirrel-sized Red Cross uniform) and contributing to the war effort by advertising war bonds.

Pilots, from whom he received fan mail, carried Tommy’s picture into battle. He was featured in Life magazine, appeared in a short film made by Paramount, and shared a radio broadcast with FDR. By 1945, the national Tommy Tucker Club had 30,000 members. If he’d been around ten years later, he doubtless would have given Mickey Mouse a run for his money on TV.

Gardeners, by and large, are not fans of squirrels. In fact—forget the Tommy Tucker Club—most are more in tune with Sarah Jessica Parker, who once announced that a squirrel is just a rat with a cuter outfit. She’s right, of course: all those fuzzy and frisky squirrels are rodents, cousins of rats, mice, chipmunks, and prairie dogs. As such, this means that they have typical rodent teeth: namely a double set of chisel-shaped incisors, with which the squirrel incessantly gnaws.

To be fair, he or she has to gnaw: rodent incisors grow continually throughout life, at the rate of about six inches per year, which means that they must be continually worn down by chewing on something. If a squirrel doesn’t gnaw, his/her teeth will continue to grow, curving inward, until they penetrate the upper and lower jaws, which is something a squirrel will do practically anything to avoid. Particularly desperate squirrels have been known to gnaw on bones, discarded deer antlers, and turtle shells—and sometimes, unwisely, on electrical wires, an act that almost always ends badly for the squirrel.

Foodwise, the average squirrel gnaws through about two pounds of food a week. Traditionally this consists of nuts, which is fine with me; and I sort of enjoy all the machinations they go through to nab the sunflower seeds in the bird feeders.

But there are limits.

Just this past year squirrels dug up and ate (ate!) all the daffodil bulbs and garlic cloves that we’d planted in the Fall, and—insult to injury—chewed huge and unsightly holes in the faces of our Halloween pumpkins.

To say nothing of what they did over the Summer to the plum tomatoes.

It’s hard to discourage squirrels. Gardeners’ anti-squirrel ploys include mint oil, cayenne pepper, disco balls, battery-powered fly swatters, electrified fences, and dogs (re: Mungo); and hardcore squirrel opponents recommend that you simply trap and eat lots of them. This last solution is particularly popular in Britain, where American gray squirrels—imported in the 1870s—have been steadily edging out the indigenous red squirrels. Accordingly, a Save Our Squirrels campaign, with the motto “Save a red, eat a gray!,” has led to a patriotic boom in British (gray) squirrel cuisine. Think squirrel curry.

Squirrel, on our side of the pond, is traditionally the prime component of Brunswick stew, a dish of uncertain but contentious origin, which—along with the squirrel—contains corn, beans, tomatoes, and (in upscale versions) a splash of Madeira. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were said to be fond of it.

Pesky as they are, though, I don’t want to eat our squirrels.

I figure they deserve some tolerance. Tommy Tucker, after all, did his bit for World War II; and—owing to their habit of burying nuts and then forgetting about some of them—foresters guess that squirrels are responsible each year for planting thousands, if not millions, of new trees.

Which, when it comes right down to it, seems a more than fair exchange for a dozen tomatoes, a few pumpkins, and even a plot of daffodils.

Previous

Previous