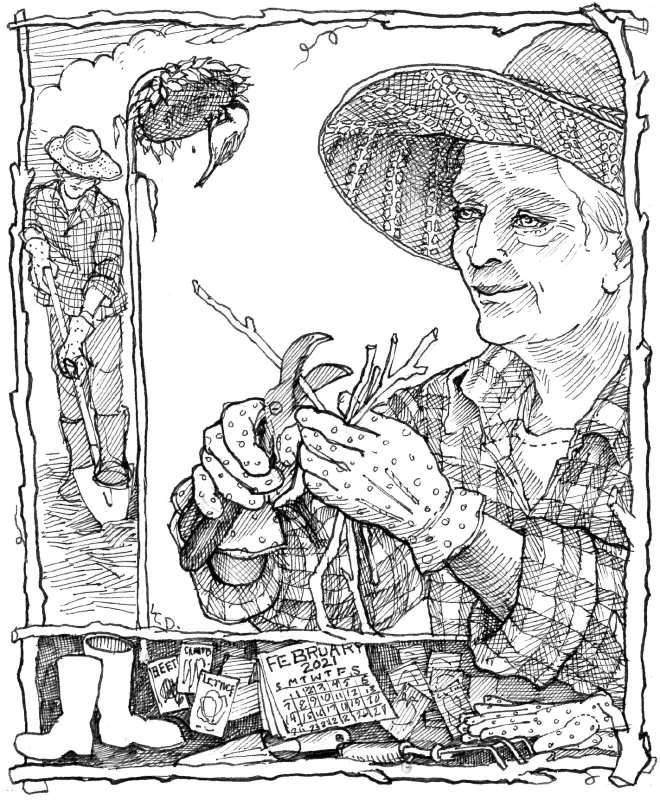

It is mid-February here in Oregon. The racks of seeds have begun to sprout at the the feed store, the earth is beginning to warm, and songbirds are beginning to return from their Winter vacation spots. For 30 years, these were signs for me to get going, as well: to begin planting kale, chard, and lettuce in the greenhouse, to set the peas out, and to buy the potato sets to put in the ground by St. Patrick’s Day.

But this year is different. For the first time, I have begun to question if I want to commit the next six months to the daily work of the garden. I am 63 years old. My body, though still able, talks to me more. My arms strain under the weight of the shovel as I turn over that first bed, my knees groan after a session of weeding. I wonder if I am up to the task.

Gardening is not for the faint of heart, and never has been.

But who am I without my garden? I rejoice that I am still eating last season’s onions. I flush with pride when I open the top of my cold frame to see lettuce heads standing with vigor. The raspberries, apples, and peaches that I froze last Fall continue to be a yummy addition to wintertime desserts. Am I really willing to forego peas picked five minutes before they are thrown into the stir-fry, buy tasteless tomatoes from the grocery store, and pay $4.50 a pound for someone else’s garlic?

What should I do? For several days, I entertain the idea of not gardening. I pass the feed store and do not go in to make a purchase. I forego checking the weather for possible rain. I walk by the garden, avoid opening the gate, and look away from the weeds that have appeared in the flowerbeds outside the fence.

I am out of sorts, adrift.

And then it comes to me. Loss. I feel a sense of loss. I want to squat in front of the beet greens, thinning them as they come up. I was looking forward to planting new strawberry tubers, so that my Summer breakfast cereal would be laden with sweet red berries. I can’t wait to stand under the seven-foot sunflowers in early August, watching the towhees and chickadees vie for the seeds that radiate from the dark black centers. I don’t want to give up the joy I know as a gardener.

On a particularly lovely late Winter day, the grapes and blueberry bushes that need to be pruned call out to me. It’s time. I put on my boots, gather tools, and head out. At first, I am over-whelmed. So much demands my attention. Part of me wants to run away. But then, a familiar knowing rises up: Just focus on one bed at a time, one chore at a time.

I start down the row of grapevines, whose tendrils weave up and over the fence to the neighboring cherry tree. A few snips here and there, and chaos transforms into calm, the new shoots snuggled into place along the trellis. The blueberries hardly need attention, so soon I am at the bottom of the garden, among the raspberry canes. As I work along the edge of the bed, choosing the canes to be eliminated so that the strongest have ample room to grow, I realize the solution to my conundrum. Just as each season, new canes grow and old ones must be culled to produce the best fruit, it is time to reconsider some of the patterns and habits that have become part of my gardening practice.

Rather than six-hour days in the garden, I can cut back to three and find others who would jump at the chance to trade their labor for produce. Instead of planting every bed to its utmost, I can let some lie fallow, or plant cover crops to nourish the soil for the next year. And instead of 12 tomato plants, I can plant half that many: the pantry holds an abundance of tomato sauce from this past year.

At 63 years, I recognize that I still have things to learn from putting seed in the ground and watching things grow. To attempt to garden like I am 30 is to ignore the cycles of life, to deny the rhythm in all of nature: the time of sprouting, then flowering, the emergence of fruit, and then the gradual dying back.

This year I will garden again, but with a new lesson, one learned from my garden. My joy does not depend on the number of seeds and starts I carry home. It comes from helping them grow, many or few. ❖

Previous

Previous