Some years back I was given a book about how to grow windowsill plants from kitchen scraps. Practically everything that you’re preparing to toss into the compost bin, says my book, can—with a little creativity and care—be turned into brand-new plants: carrot tops, scallion roots, garlic cloves, squash seeds, and even things that ordinarily wouldn’t be caught dead sprouting in Vermont, like pomegranates and papayas.

This wasn’t as easy in practice as the book made it sound, at least for me. I managed to sprout a few lemon seeds—which, so far, show no sign of developing into lemon trees; avocados were a bust; and so were pineapples which, at least according to my book, should have been a walk in the park. All you do to grow your very own pineapple is cut the top off an existing one, stick it in soil in a pot, and water it. My pineapples, however, clearly knew they were in a hostile environment. They weren’t having any. I couldn’t really blame them. From our windowsills, you can see snow.

Historically, a lot of people have been defeated by pineapples.

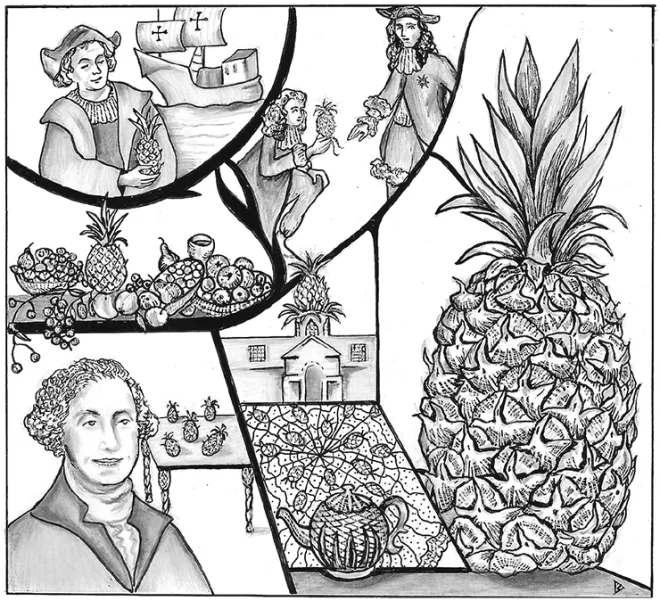

The pineapple is a native of South America, though by the 15th century, when Columbus arrived, it had spread north through Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean islands. Columbus happened upon it in 1493 on the island of Guadaloupe. According to his log, he and his men came upon it in a deserted village. The perspicacious natives, spotting the foreigners, had fled to the hills, leaving behind calabashes filled with fruits that to the Spaniards looked like enormous “green pine cones.” Columbus pronounced them delicious.

The few pineapples that made it back to Europe—most rotted in transit—created a sensation. Only the very rich could afford them, and a pineapple, crowning a pyramid of fruit on an after-dinner banquet table, was the ultimate sign of status and luxury. Today it’s yachts and gold bathroom fixtures; in the 17th century, it was pineapples.

Even the very wealthiest, however, couldn’t always get them. The slow-ripening fruits were nearly impossible to grow in Europe, where the climate was neither warm nor humid enough to suit them. In the 1670s, England’s King Charles II famously had his portrait painted showing the Royal Gardener kneeling at his feet and presenting him with a pineapple. (Whatever the implication, this certainly wasn’t homegrown fruit. We know that Charles ordered his pineapples from Barbados.) The first all-English pineapples were only produced some 40 years later by Henry Telende, a gardener on an estate in Richmond. Telende’s technique involved nurturing the plants under cold frames in pits packed with manure and tanner’s bark—an oak bark used in leather tanning. When soaked in water, tanner’s bark fermented slowly, generating a constant, comforting, electric-blanket-like heat.

It wasn’t easy growing pineapples: especially in the early 1700s during the Little Ice Age, a period of ultra-cold winters, so cold Londoners held festivals on the frozen Thames.

The real secret to providing pineapples with a congenial home away from home was a greenhouse. Greenhouses of one kind or another date back to Roman times—the earliest seem to have been carts covered with oiled cloth, on which the Emperor Tiberius’s gardeners grew cucumbers. But in the 17th century, the Dutch held the lead in state-of-the-art greenhouse building. (Reportedly, the Dutch had produced pineapples in their greenhouses as early as 1680.) Inspired, soon everyone who was anyone across the continent had leaped on the pineapple bandwagon and was scrambling to build greenhouses—called pineries if exclusively devoted to pineapples.

Pineapple motifs were ubiquitous. Pineapples appeared in stone on gateposts, in wood on staircase finials, and in metal on weathervanes; pineapples were woven into carpets and table-cloths, printed on wallpaper, and painted on chairs. John Murray, the Fourth Earl of Dunmore—the last colonial governor of Virginia—put a roof on his Scottish Summer house in the shape of a gigantic pineapple. Men carried pineapple-shaped snuffboxes. Wedgewood produced a line of pineapple-decorated china and Staffordshire made pineapple teapots. “No garden is now thought complete,” wrote one 18th-century botanist, “without a stove for raising of pine-apples.”

The American colonists were equally taken with the high-status pineapple. George Washington, who first tasted them at the age of 19 while on a trip to Barbados with his brother Lawrence, ordered pineapples by the dozen for the table at Mount Vernon. Americans, however, didn’t throw themselves into pineapple cultivation with the fervor of their European neighbors. In the days leading up to the Revolutionary War, the colonists were boycotting the importation of British goods, among them an essential component of greenhouses: glass.

The Townshend Acts—named for Charles Townshend, British Chancellor of the Exchequer—took effect in 1767, charging import duties on items the British hoped the colonists would be unable to produce on their own: glass, china, lead, paint, paper, and tea. The revenues were intended to help pay for the crushing cost of the recently concluded French and Indian War and to show the colonists—who had a distressing bent for disrespect and disobedience—who was boss. Americans protested vociferously. In the fraught political climate, pineapples—viewed as suspect British luxury goods—dropped from sight as social desirables.

Raising a pineapple was expensive. The fruits could take two years or more to ripen. The constant care, plus the coal needed to heat the pineapple-encasing greenhouses, meant that each fruit, by the time it was ready to pick, was worth an estimated $8,000 in today’s money. Those who managed to acquire one of these often didn’t eat it. Instead, it was displayed for as long as possible in order to maximize social cachet before it began to go bad. Sometimes a single pineapple was shared among friends, who passed it from dinner to dinner and house to house—though the servants tasked with delivering the valuable pineapple were frequently targets of thieves. And pinching a pineapple was serious business. Those who got caught were subject to deportation and seven years of hard labor.

The less well-off but still socially ambitious could rent a pine-apple for special occasions from one of the many pineapple rental shops that sprang up across Britain at the height of the craze. For a small, affordable sum, you could show off the pineapple for an evening, bask in its reflected glory, and then sneakily return it in the morning.

Which to me, given my experience with persnickety, if not downright resentful, pineapples, sounds like a really good idea. ❖

Previous

Previous