For 25 years, my husband and I have gardened, composted, and planted natives on a quarter acre in our small Oregon city. We shaped the yard into zones, raising veggies, building a greenhouse, creating sunny lawns, growing apples and planting wildflowers under the shade of tall Douglas firs. We’re not the only ones who love living here: over the years, raccoons slept in the trees, Cooper’s hawks nested there, and swifts raised their young in our chimney.

Two decades of dry Summers left Oregon tinder dry by the beginning of 2021. And then, in early Spring, the rain stopped falling. The ground was pounded to dry clay, and every flower, berry, green bean, and apple showed the effects of too little rain. Bugs nearly vanished. Baby birds grew to just 2/3 of their normal size—there wasn’t much to eat and little fruit to steal from the berry farms. Grass not only browned out, but there were fewer ants and spiders. By Midsummer, we hadn’t heard the croak of a single tree frog.

I’ve gardened for a lifetime, starting in Iowa, a Jack-and-the-Beanstalk place where everything grew in thick black soil laid down long ago on the prairie. The most common visitors to my garden there were raccoons. I knew my sweet corn was almost ready when I saw little tooth marks on a few ears.

My second garden was behind our first Oregon home, planted in the clay and construction debris left after the builder hauled the good soil somewhere else. Years of composting led to growing plums, cherries, and a big veggie garden, all highlighted by backyard barbecues featuring pies made from our own fruit—and by Spring raids on our garden beds by the scrub jays when we churned up the hazelnuts they’d stashed in the soil.

My third garden is behind the house, a mile from the river in one direction and a quarter mile from a field full of cows in the other. Nuthatches, chickadees, towhees, and hummingbirds flit by as we mow, weed, and water. After all, we’ve lived here for several of their generations. Even after 25 years, we still meet new species, like the tiny but feisty Douglas squirrel, who complains loudly from the trees and frantically steals pine cones and sunflower seeds. We’ve seen a lot over the years—and learned to cover every new planting with chicken wire or hardware mesh, so squirrels and birds won’t grab all the seeds or scoop out the bulbs for snacks.

But we never had a Summer like 2021.

One day late last June, the temperature soared to a record level and hovered there for hours. Our tomato plants and lettuce sagged in clouds of dust. Even at sunset, the air baked at 90 degrees. My neighbors and I hid inside, rushing out at dusk to frantically water the wilting peppers and beans. The stars pierced the midnight blue of the sky, glittering with more clusters and galaxies than we’d ever seen, in such low humidity that even the bats quit hunting for bugs. The season was eerily quiet, just the buzzing of air conditioners, the hissing of sprinkler jets, and the sound of a car passing now and then.

The second frying day, on its way to 110 degrees, began hazy and still. At 5 a.m., my husband woke me with a whisper: “There’s a deer in the backyard under the apple tree.” Our yard is enclosed in six-foot fences and seven-foot hedges, but a yearling doe stood and calmly ate underripe Granny Smiths off our apple tree, rolling them around in her mouth like marbles and staring at us.

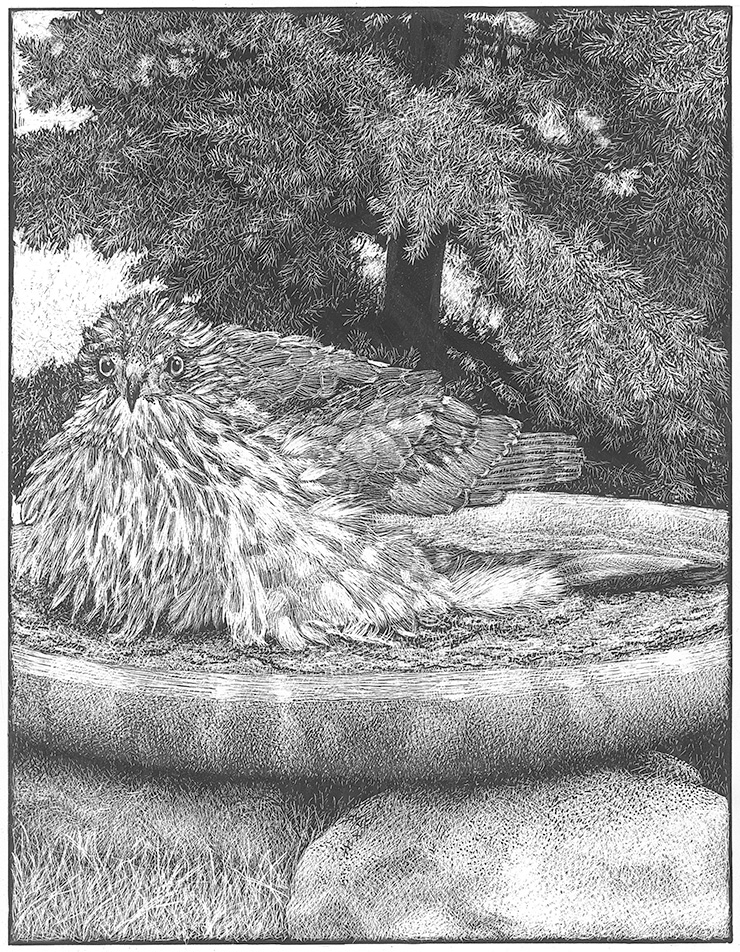

That night never cooled below the mid-80s. After drenching the garden with a hose, we filled the birdbaths in the shade to slopping full and aimed a plant mister that direction. By 9 a.m., a female Cooper’s hawk landed in the birdbath. She stood there, panting, the entire day, fanning out her feathers, sipping water, and staring down any bird that got close. All day, she guarded her water supply—unafraid of the people watching in disbelief from the window.

The fourth day, before the temp peaked at 114 degrees, a huge juvenile red-tailed hawk stuffed itself into the birdbath, fluffed up, and didn’t budge—until sunset.

The blackberries desiccated and fried brown on the bushes that week. Leaves on trees scorched black. Everything stopped growing for two weeks, sopping up any water found anywhere and later sprouting thin, haggard stems. Surprisingly, some cool-weather crops like leeks, shallots, kale, and herbs managed to survive, but peas (Asian and snap) petered out rapidly, roses died outright, and even ever-hardy zinnias were wan and forlorn. Still, nothing was as astonishing as all the birds and other critters that came to our garden.

Most of them are still here.

All gardeners know that what we really sow when we plant our gardens is hope. We hope for juicy fruit, interesting new discoveries, and a full freezer for the Winter. But until last Summer I never realized that we were planting hope for tired, disoriented animals, as well. Our garden became their refuge, a place where they could still find some slugs, berries, bugs, and water during a brutal Summer.

Out there somewhere, somehow, even the fragile little frogs made it through the heat. They started croaking again in September.

I used to believe the animals should be grateful to us for building this oasis of food, shade, water, and rest. But the garden is our refuge, too. It’s where we go, for shade and activity, for herbs and replenishment.

So after the Summer of 2021, I am grateful to them—for giving me just a tiny reminder of how interdependent we all are. ❖

This article was published originally in 2022, in GreenPrints Issue #130.

Previous

Previous

Oh, how I loved this story! Now we are in 2023 and most of the country is seeing the extremes of heat and lack of water described by the author. It seems a mandate for us to plant the most hardy native plants we can, add bird baths and ponds, and create an oasis for humans and animals. One we can share and enjoy as we plan for an uncertain future.