Again, an intrusion of aphids has found its way to the bridal wreath bush in my Maryland garden. The assailants have slowly drained the graceful shrub of its vitality. Year after year I’ve watched passively, hoping the natural order of things would mitigate the problem. Not this year. This is the year I will fight back!

But just before I can launch a counterattack, my tactic is intercepted: Mother Nature intervenes with a plan of her own.

A bridal wreath bush (Spiraea prunifolia ‘Plena’) in full display overflows with old-fashioned charm. Frilly, double-flowering blossoms ornament bare branches the way lace embellishes an Edwardian frock. In early Spring, diminutive white pearls emerge along leafless stems, gently unfurling to become creamy-white, button-sized roses.

Shortly after the blooms fade, leaves emerge. On my shrub, that’s when aphids appear. They cluster at the tips of stems where new growth provides easy access to flowing sap. These feedings disrupt the juices in the vascular tissue, weakening the plant and causing new leaves to curl up and turn brown. Though the bush survives the attack, for the remainder of the season it appears lackluster. Each subsequent Spring, fewer and fewer blooms emerge.

To destroy the aphids without synthetic pesticides, organic gardeners suggest a mild solution of soapy water sprayed every other day for a few weeks. I try this, but with little effect. (In all honesty I must admit that I am not as diligent at spraying every other day as directed, and I miss a few applications.) I consider purchasing a chemical pesticide: on the one hand, the spray will bring instant gratification; on the other, what collateral damage accompanies the use of a poison?

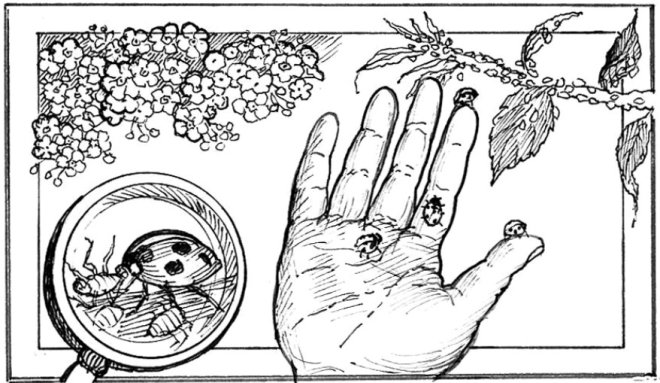

Luckily, the dilemma is quickly resolved by the arrival of a ladybug. I’ve always associated ladybugs with good luck, though I’m not sure why. Knowing that aphids are a favorite food of ladybugs, I gently swipe the tiny red beetle into my hand and lift it to a site of infestation. It appears indifferent to the feast and quickly crawls away. I try again, this time clumsily knocking the creature to the ground. Perhaps there is a greater plan in motion here, and my interference is not warranted.

A day or so later, I’m utterly astonished to see a dozen ladybugs crawling around in the bush. They have found their way to the aphids—and what voracious predators they are! Grasping the pest with their two front legs, they lift it to their mouths where it quickly disappears. Then they scuttle off to the next aphid.

Over the next few days, hundreds of ladybugs have found their way to the bush—truly, hundreds! At first glance, it appears the shrub is adorned in red berries. The ladybugs make short work of the aphids. As days go by, the aphids disappear, and the number of ladybugs decreases until just a few remain. Like soldiers, they march up and down each stem. I imagine them conveying, “Section eight, all clear.” Several days later, all of the ladybugs have departed and the bush rests, aphid-free.

I am curious to find out more about this beneficial insect and, in particular, their historical association with good luck. King Robert the Pious (972-1031) of France halted a beheading because of a pesky ladybug. A condemned man was about to be executed when a ladybug flew down from the heavens and landed on the condemned man’s neck. The executioner swatted it away, but the ladybug persistently returned to land on the condemned man’s neck. King Robert interpreted the event as a sign of un bête à bon Dieu—a beast of the good God. The king quickly pardoned the condemned man, and it was later proven that the man was actually innocent of the crime.

Research reveals that in the Middle Ages, the ladybug was first referred to as the “Lady Bird,” recognizing both the insect’s ability to fly and its association with Our Lady the Virgin Mary. In early paintings, Mary is portrayed wearing a red cloak, the same color of the ladybug’s forewings. (Near the end of the Middle Ages, as the blue pigment from lapis lazuli rises in prestige, Mary is then painted wearing a blue cloak, but with red clothing beneath.) The seven spots of the ladybug are said to symbolize the Virgin Mary’s seven joys and seven sorrows.

Historical accounts reveal why the ladybug is named in Mary’s honor and the genesis of its positive connotations. From a theological lens, the period sees a fascination with Mariology—the study of Mary: doctrines touting Mary’s grace, faith, and intercession are widespread. From an economic lens, the period is primarily agrarian: society is wholly dependent upon a robust harvest for survival. Seeking relief from pest invasions, Christian communities would gather with clasped hands and bowed heads, whispering supplications to the Virgin Mary for special protection in the fields.

According to legend, it is the strength of collaborative prayer that summons the ladybugs from heaven. The villagers had never before seen this bright red flying beetle when it suddenly appears in the fields in great multitudes, making fast work of the aphids, and then disappearing as quickly as it had come. The crops are saved, harvests reaped, and the community is positioned to survive another Winter. Believing that it is Our Lady the Virgin Mary who sent the savior-bug down from heaven, they name the tiny red beetle in her honor. Thus, the association with ladybugs and blessings was born.

Ladybugs lay eggs on the undersides of umbrella-shaped wildflowers such as Queen Anne’s lace and dandelion. In the garden, ladybugs like the undersides of yarrow, tansy, and dill. I have grown those plants near my vegetable garden for at least a decade; perhaps that’s where my loveliness of ladybugs originated.

The Summer after my experience at the bridal wreath bush, I am out weeding the vegetable garden, and it begins to rain. As I run about gathering tools, the heavens open to release a heavy downpour. Heading toward the house, I happen to pass by a row of tansy whose tight yellow clusters stand erect on tall stems, like umbrellas dancing in the wind. I wonder. I stoop to examine their undersides. Sure enough, there, beneath the canopy of blooms, are ladybugs! They are snug and dry, quite protected from the pelting rain. I will forever think of those flowers as ladybug umbrellas.

Although I have a number of insect problems in my vegetable garden, I’ve never had a problem with aphids or spider mites. I appreciate ladybugs and their special tastes for the tiny pests that attacked my bridal wreath. Legends are one way that communities pass knowledge between generations. Legend reveals the Lady Bird brings blessings, and—through experience—I now know this to be true. Whenever you see one, know that divine providence is watching over you, and good fortune is on its way. ❖

Previous

Previous