In the 1950s, Hudson, New York had two large cement plants that employed hundreds of men.

It was a dirty job but paid a livable wage. My father was employed at one of the plants. The smokestacks from the kilns, each at least 100-feet tall, sent cement dust far and wide. As a child, I thought little about pollution—I’d never even heard the word. But we lived with it every day. All around Hudson, sticky cement dust fell with the early morning dew. Local farmers joked, “One thing for sure, we never have to lime our fields!” In town, it settled on cars parked in the streets. Porches, sidewalks, and outside stairs were heavily dusted with the gray, clinging dust—especially in the Summer months, when the humidity made it stick to everything.

My mom would go out every morning around 6 a.m. and wash the porch and sidewalk with vinegar. It was the only thing that unglued the stubborn film. She would spray her front rose garden with soapy water, changing the leaves’ color from white back to green. A young girl, I would sit on a side bench with my coloring book, talking with my mom and watching her scrub the sidewalk with her wet, stiff broom.

In 1952, the year I turned 7, a drought began in June—and continued through September. Temperatures soared into the high 80s and often into the 90s. The humidity became oppressive. But the dust never seemed to give up! In August, the city declared that there would be no outside watering. That meant that neither cars nor sidewalks could be washed—and gardens certainly could not be cleaned or watered. The day we heard the announcement on the radio, Mom twisted her dish towel so tightly I thought it was going to tear, carrying it with her and wringing it frequently.

That night at dinner, Mom declared that any water used in the sinks would now be collected in pails. “Use the stopper. Don’t let the water run down the drain.” She saved the water from her ringer washing machine. Bath water was collected in pails and placed on the back porch. In the morning, Mom would wash the porch and sidewalk and sprinkle her front rose garden and backyard. Only now she was using what I called “yuck water.”

When our car turned white with pasty dust, Mom sent us kids to tow pails of water from the nearby creek, add vinegar, and use that to get the cement dust off the car. My mom and dad went to a local farm and asked if they could collect three-year-old manure. They mixed the manure with dirt and mounded it around the roses—to both fertilize them and help keep the roots from drying out. Mom did all her flowers in the backyard the same way.

Mom’s determination showed me that there’s always a remedy if you don’t accept the status quo. That Summer her roses grew wonderfully. Our neighbors could not believe they were so healthy and beautiful. There weren’t any aphids, bugs, or leaf rust. The household water not only kept Mom’s plants alive, the leaves shone like never before.

The following Summer, Mom continued to collect and use the soapy water.

The drought ended in 1953, and the cement plants closed in the 1970s. Today, most of the people living in Hudson do not remember the 1950s. Many come from New York City. The air is clear, and the roads and cars are not colored with cement dust.

And many people today know almost nothing about the sacrifices their own families made just a few generations ago. My mother, Anna, was born in 1910 in Galicia near the Carpathian Mountains in Ukraine. She witnessed WWI—when her father was sent to a Russian prison. When he was released—seven years later— he traveled to America and settled in Hudson. He saved and bought passage for my mom, age 17, and her younger sister and brother.

My own father was a soldier in WWII. He sent his paychecks home to Mom. Unbeknownst to Dad, Mom used the money to buy a house in Hudson before he came home.

My mom always loved and defended America. When our neighbors complained about taxes, the cost of living, and how difficult it was to make ends meet, Mom would say they needed to live where people died of starvation, trying to make it through a war. Mom witnessed the dead lying in the roads and animals slowly dying of hunger. She told her neighbors that paying taxes was a privilege for security and peace of mind.

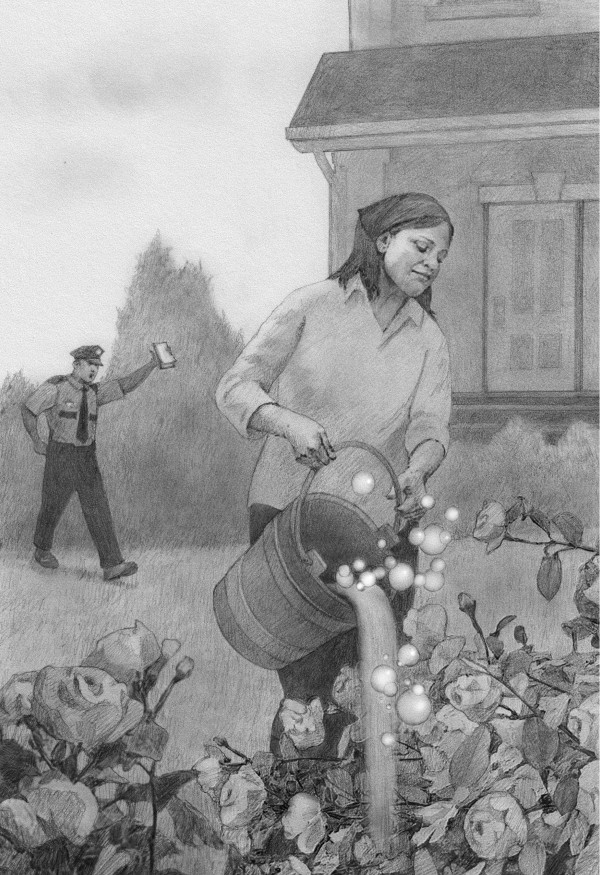

When the no-outside-watering restriction was first announced, many of our neighbors complained loudly. My mom just started reusing our household water. One morning two weeks later, a policeman arrived at our house while Mom was scrubbing the sidewalk. The officer pulled out his ticket pad and started to issue her a summons.

Mom held her pail out to the officer and said, “I dare you to drink this water.”

The police officer looked at the brown soapy water sloshing in the pail—and ripped up the summons.

After he left, Mom sat down on the stoop, bent over, and covered her face with her hands. She was crying!

I hugged her from behind. “The policeman went away, Mom,” I said. “Why are you crying?”

Her voice, when she answered, was soft. “Ever since I was a child,” she whispered, “I am afraid of police.”

She never told me any more about it.

Today, every time I water my flowers, I think of that Hudson drought and my mom’s fight against the cement dust. I love my flower gardens. They give me joy and tranquility on a spiritual level. Would I have the energy and resolve to make the sacrifices for my garden that my mother did for hers?

My mother never even asked herself that question. ❖

Previous

Previous