Read by Matilda Longbottom

A little boy I once knew was passionately devoted to his toy penguin and could not be parted from it. On a long journey, he was holding the penguin out of the car window when it was discovered that somewhere, perhaps miles back, its body had fallen off, leaving the child lovingly grasping one flipper. Those who have had small children can appreciate the magnitude of the disaster. These parents thought of “going back,” but the journey had been from England to Scotland-hundreds of miles might be involved.

Luckily, the Scottish grandmother whom they were visiting knew exactly what to do. She went out immediately, bought a Teddy bear, and sewed the remaining flipper onto its breast. The Teddy remained with the child until (and even after) he be came a man, long after the attached flipper had worn away.

Marianne North, the intrepid Victorian botanist and artist, writes in her Recollections of a Happy Life of a naturalist in Brazil who was sur rounded by the most glorious tropical paradise and had a large collection of rare orchids, “but his chief pride was in one wretched little cherry-tree which after ten years of watching, had produced one miserable little brown cherry: He had brought the original stone from his dear native Belgium and it reminded him of home.”

Winter is a time of nostalgia and, curled up by the fire, we dream of gardens, not only our own gardens in summer but, perhaps even more, gardens we have left behind. As an immigrant from England, I feel sympathy for the early American settlers who, leaving all they knew, brought with them reminders of home, often little plants or bulbs tucked into the crevices in baggage. We now know that some of these plants could become problematical in a new environment, so we are slower to introduce and exchange plants than we were. Even so, gardeners are still apt to want “rarities” rather than what surrounds them and winter garden catalogues are quick to promote them.

This desire for the unusual is what sent our ancestors exploring all over the globe for exciting intro ductions. Their trips were not gentle botanizing but real adventure. The list of botanists who risked or even lost their lives to bring back plants is a long one. Attacks from natives, cold, and hunger were constant threats. In the warmth of our living rooms, with catalogues of the hundreds of plants now available, it is amazing to think of what they did, and why.

Plant explorers were not ordinary Travellers, even when travelling itself was not easy. They had to carry everything they needed into remote, inaccessible areas. This included pens and inkhorns to make notes and rec1ms of heavy paper for pressing specimens. Seeds and plants had to be prevented from rotting and yet not dry out. There was little room left for clothing, comforts, or even food. They lived off the land as they could.

David Douglas, who first brought so many of our plants from the West Coast, describes rats eating his shoes and ink case. When he got soaked, which was often, he simply took his clothes off and sat by the fire. He once had to eat all his collection of seeds and, later, even his horse. He pacified hostile Indians by giving them the buttons off his coat.

Linnaeus’s luggage was similar. It included ink and paper, a magnifying glass, his manuscripts on ornithology and flora but only one extra shirt, two-night caps, and two “half-sleeves” in the way of clothing. Explorers often slept on the open ground with no tents-William Bartram describes waking up to find an alligator’s open mouth a few feet away from him. Luckily, he was able to stay awake the rest of the night, helped by biting mosquitoes and owl cries vibrating through the forests “in dreadful peals.”

It’s easy enough for us to order plants that were introduced after such adventures. Sometimes going round my garden, I think of what it took to get them there. Forsythia makes me think of Robert Fortune sneaking into the forbidden interior of China wearing a false pigtail. A Regal lily in bloom makes me thank Ernest Wilson, lying on his back on a narrow mountain pass while forty mules going the other way stepped over his rockslide-shattered leg.

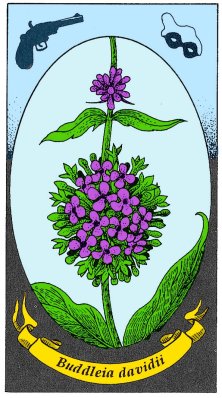

John Bannister, who found the beautiful bloodroot and Virginia bluebell, both of which I have in abundance, fell off a cliff while botanizing and died. The Cunninghamia by our pond, an evergreen from China with foliage not unlike that of a monkey-puzzle, was named for James Cunningham, who was the only survivor of a massacre and was later both wounded and imprisoned. He eventually died at sea. My Buddleia davidii, often covered with butterflies, was first sent back by Jean Andre Soulie, who was killed by bandits. George Forrest collected the ancestors of many of our rhododendron.

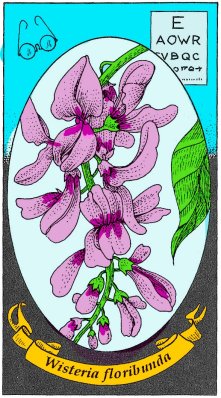

He narrowly escaped being massacred in Tibet by rolling off a path into the jungle and hiding there with no food but a handful of peas and without even his boots, which he removed to prevent being tracked. I have Japanese wisteria and the “PG” hydrangea both introduced by Jean Siebold. He performed the first cataract operations in Japan where, in exchange for restoring sight, he would be given new plant specimens. He was finally imprisoned and barely pardoned for obtaining a map of Japan at a time when that was a capital offense for foreigners.

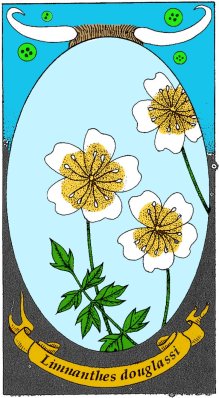

I sometimes plant “poached egg plant” to attract bees-and think of David Douglas when it flowers. I have a particular affection for Douglas, not only because of the many plants he introduced (including, of course, the Douglas Fir), but also because he wore a suit of flamboyant Stuart tartan in the remotest wilderness in case, he should come across fellow Scottish Travellers. He died in Hawaii by failing into a bull pit while botanizing. I don’t grow saffron crocus but do use it in cooking, while thinking of the legendary pilgrim who brought it back hidden in his hollowed-out staff, “for if he had bene taken … he had died for the fact.”

When we order from catalogues, we expect plants to arrive in prime condition and, if they do not, are quick to demand replacements. In the past, attempts to send hard-won plants home intact were more often unsuccessful than not. This added to the quantities collected quantities which now horrify us for most could not be expected to reach their destination.

Plant explorers of the past searched as ardently for ways of keeping their finds alive as they did to acquire them. Bernard Jussieu was said to have brought the first Cedar of Lebanon back to Paris in his own hat and to have shared his water ration with it. Peter Collinson, who received seeds and plants from John Bartram, was always writing with new suggestions to pro tect specimens-such as using ox bladders to contain the earth packed roots of a plant while the rest, tightly bound, would stick out of the neck. Linnaeus advocated putting seeds into a bottle of sand and placing that bottle into a bigger one, which was, in turn, filled with a mixture of nitre, salt, and sal ammo nia. John Evelyn suggested that “plants or rootes that come from abroad will be better preserved if they are rubbed over with honey before they are covered with moss” for “honey has a styptic quality to hinder the moisting that is in the plants from perspiring.” Sometimes seeds would be covered with beeswax or lard, then wrapped in arsenic-soaked paper to protect them from mice and rats.

The invention of the glass Wardian case in 1834 considerably improved the chances of plant survival. This airtight case protected the contents from salt air and maintained a constant damp atmosphere. If created earlier, it might have helped pro tect some plants from more than salt: The arrangements for transporting the breadfruit plants on the Bounty in 1787 had meant sacrificing both cabin space and fresh water to them factors in the famous mutiny. (That mutiny caused the death of yet another botanist, Nelson, who was set adrift with Captain Bligh and died before reaching home.)

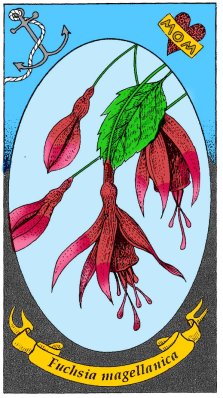

Severalsea captains had a small busi ness in transporting plants like the first “tea roses,” which came along with tea shipments from China. Sailors, too, probably brought many plants back from abroad. They’re known to have planted anti-scorbic plants like citrus and rhu barb wherever ships called routinely. There is a nice story that the Fuchsia was first brought to England by a sailor as a present to his mother. It was then spotted on a windowsill by the nurseryman Lee, who, unable to persuade her to part with it, “borrowed” it from her for eight guineas and propagated it.

Even with so many plants to choose from, the word “rare” immediately catches my eye, as it has for gardeners always. Peter Collinson wrote disarmingly to John Bartram that he was “ready to Burst with Desire for Root, Seed or Specimen of the Wagish Tipitwitchet Sensitive.” All of us know the pleasure of showing a Neighbour an unusual plant we have managed to raise. Most of us are less ingenuous than Peter Collinson, firmly but casually leading our visitor to the spot next to the plant we wish to show off. Real friends will immediately ask about the plant they do not recognize (those who do not ask are probably not real friends and can be discounted). Then we remark blithely, “Oh, that? Yes, I’m quite pleased with it. It’s a Pseudo vanitas erectus, and it’s the first time I’ve tried it. I wanted to see if the flowers were really green…”

I might try a little subterfuge to draw attention to a rarity of mine, but sometimes plant collectors of the past were outright dishonest. In the early seventeenth century, a Mon sieur Bachelier had some anemone plants from the Middle East which he would not share with any other collectors. He was finally outwitted by a Dutch Councillor of Parlia ment, who visited the garden and “accidentally” dropped his fur cloak on the border where the anemones were growing. His servant, primed beforehand, scooped up the cloak and, with it, some adhering seeds. The plants grown from these were known as “French” anemones.

Another collector, the Duke of Devonshire, along with his famous gardener Paxton (who was the first to bring the Victoria amazonica to flower and designed the Crystal Palace) was so keen to have the first Amherstia nobilis that the Duke hired John Gibson to go to India and bring one home.

Hortus describes the Amherstia as “one of the noblest flowering trees” and, to add to its attraction, it had hardly ever been seen in the wild but was discovered in a neglected monastery gar den. Gibson did find one and was described as running round it “clapping his hands like a boy who has got three runs in a cricket match.” The tree destined for the Duke of Devonshire died on the voyage home, but there was another on board which was a present from the Director of the Botanic Gardens in Calcutta to the Directors of the East India Company in Lon don. This plant was met by Paxton and whisked down to the Duke’s estate at Chatsworth by a special fast canal boat. The Duke then wrote to the Directors of the East India Company, “It was necessary to remove the plant from the ship-I shall, however, be most ready to return the Amherstia when ever you demand me to do so.” Needless to say, the Amherstia stayed at Chatsworth!

I love the passion of these plant collectors and wonder if, with so much available, we aren’t a little jaded these days. Not much notice is taken now when new plants are discovered. Compare this with the introduction in 1788 of the Hydrangea hortensis. Ernest Wilson wrote about its arrival in London: “It was met on the docks by a delegation of plant enthusiasts and patrons of horticulture, including Sir Joseph Banks. After the ceremony attending the plant’s arrival and inspection, a breakfast in its honor was given.”

I have two hydrangeas, and I put aluminum sulphate around them to make their blooms a brilliant, unrealistic sky blue. I sometimes have my own breakfast on the terrace next to them. Once they were in bloom beside an arch covered with Heavenly Blue morning glories, whose breathtaking show lasts only a few hours. For that moment, I was perhaps worthy of the sacrifices and triumphs of those plant hunters of the past, because I de cided to have, if not a breakfast, at least a viewing in the plants’ honor. It was 6:30 a.m., but I had one friend whom I knew I could call.

“Come right over and see something beautiful,” I said. With true plant-lover’s passion, she came. ❖

Previous

Previous