Read by Matilda Longbottom

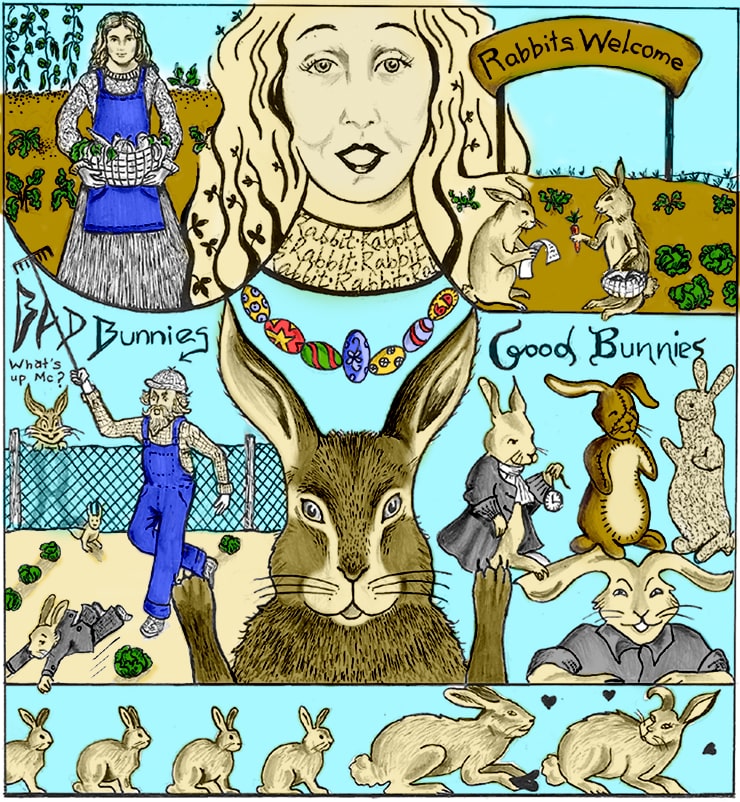

In our family, it’s always been the custom on the first day of every month—before speaking a single word, not even “Good morning” or “Coffee, please”—to lean out the window and yell, “Rabbit Rabbit!” Supposedly this guarantees good luck for the coming month, and though countless past personal examples—transmission failures, rejection letters, sprained ankles, funerals—make this look a little iffy, I’m afraid to give it up.

I mean, without “Rabbit Rabbit,” things might be even worse. Of course there’s the possibility that we’ve got “Rabbit Rabbit!” all wrong.

According to Wikipedia, rabbit-yelling has been around since at least 1909—but no one agrees as to the ideal nature of the yell. Depending on who and where you are, the crucial luck-generating rabbit yell may be a triple header—“Rabbit Rabbit Rabbit!”—or a colorful “White Rabbits!,” “Brown Rabbits!,” “Black Rabbits!,” “Grey Rabbits!,” or even (please) “Rabbit! Bunny!” which I think we can all agree is silly.

But obviously there’s something to it. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a rabbit-yeller, and—hey—we won World War II.

Just saying.

Gardeners, however, tend to be torn about rabbits.

We’re all raised to love rabbits. Babies are introduced to books with Dorothy Kunhardt’s fuzzy Pat the Bunny. The Easter Bunny brings us jellybeans and chocolate eggs. The star of Margery Williams’s The Velveteen Rabbit is a total sweetheart who, at the end of the book, is transformed from a stuffed toy into a real live bunny. Peter Rabbit is naughty, but endearing.

Other favorites include Warner Bros.’s snarky Bugs; Harvey, the giant rabbit—visible only to Jimmy Stewart; Alice’s perennially late White Rabbit; Uncle Remus’s Br’er Rabbit; and all the personality-laden rabbits of Richard Adams’s all-rabbit novel, Watership Down.

I have friends who raise rabbits, and those rabbits are adorable. They have names like Blueberry, Muffin, and Olivia. Pictures of them are posted on Facebook. People compete to adopt them.

But here’s the catch. Real bunnies eat.

Rabbits in the wild live on weeds and grasses, which diet allows them to breed like—well, rabbits—producing up to twenty offspring a year. Given this enthusiasm for bunny-making, rabbits unchecked can be disastrous. They were introduced to previously rabbit-less Australia in the late eighteenth century in an ill-advised attempt by colonists to make their new home look more European. By the 1920s, the many-times-great-grandchildren of the initial importees amounted to some ten billion—yes, billion—rabbits, who had spread across the continent and were eating pretty much everything in sight.

In Watership Down, Adams’s rabbits have a language known as Lapine. The Lapine word for rabbit-grazing is “silflay,” which means roughly “to eat outdoors.” Silflay is what the Australian rabbits were doing when they stripped the landscape and what the rabbits around here are doing when they hop into the garden and eat our lettuce, beet tops, parsley, cilantro, and spinach.

Wretched rabbits, I thought.

In Peter Rabbit, the gardener, Mr. McGregor, is clearly the bad guy. He chases Peter with a rake, causing him to lose both his shoes and his new blue jacket; he bellows at Peter; he tries to catch Peter in a sieve. Anybody reading Peter Rabbit roots for Peter. The thing is, though, when the first thing you see in the morning is the awful aftermath of what rabbits have done to your brand-new patch of lemon basil, you start to see Mr. McGregor’s point of view.

There are a number of techniques—I instantly looked this up—for keeping rabbits out of your garden. Prime solution is a rabbit-proof wire fence, partially buried, so that they can’t burrow under it. Other anti-rabbit devices include scattered coyote urine (tricky to come by), or Ivory soap, vinegar, or chili powder—though these last three, rabbit experts admit, are short-term, since rabbits quickly get used to them.

Or you can sit back and hope that nature will take its course.

Around here, we’ve got a lot of wildlife. We’ve got deer, bears, raccoons, possums, skunks, fisher cats, muskrats, beavers, squirrels, and chipmunks. We’ve also got a booming population of foxes, two of whom this past year raised a double litter of eleven in a den across the field, a family so charming that it was all I could do not to kidnap one.

Rabbits. Foxes. It’s hard not to see an active food chain here. In theory, left to their own devices, rabbits and foxes should reach a population equilibrium such that there aren’t too many of either. For all I know, that’s happening, though you can’t tell by our garden. All that persistent silflaying tells me that somebody out there in food-chain world isn’t doing his or her job.

I’d just like some respect for boundaries. That is, I’d like the wildlife to stay where it belongs. Squirrels, for example, don’t necessarily do well in the house: When one fell down the chimney last summer into the (mercifully cold) woodstove, it took three of us to extricate him, a task which involved dismantling the stovepipe. Released, he shot off into the trees like a bullet, and we suspect he’s dining out on the story, because there hasn’t been a squirrel in the house since.

Field mice are fine in the field, as opposed to—say—eating the paper off the soup cans in the kitchen cabinets; and I could do without that herd of thuggish raccoons who keep knocking over the garbage cans. You keep to your side of the line, is what I say, and I’ll keep to mine.

So what to do about all those rabbits? A good solution for a rabbit-invaded garden, rabbit experts say, is even more garden. Plant a decoy garden of preferred rabbit foods some distance away from your main plot and hope that they’ll chow down there.

I’m willing to give it a try. It seems like the generous thing to do, especially since rabbits, at least just possibly, have been providing us with many months and years of good luck.

What if you forget to yell “Rabbit Rabbit!,” which some of us periodically do, even if helped along with a sticky note pasted to the alarm clock. Are you then doomed to a month of flat tires, sinus infections, missed appointments, and family feuds?

Not at all. At the end of the day, before going to bed, go to the window and yell “Tibbar! Tibbar!”

That’s “rabbit” spelled backward. ❖

Previous

Previous