As an urban child, I had never seen a cultivated garden. The closest thing I knew to one was a circular patch of dirt, bordered by a concrete curbstone, in the middle of the inner courtyard of our apartment building. It was planted with a half-dozen untrimmed privet bushes. The small, dark green leaves of these spindly shrubs were often spotted with fragments of soot that fell in black flakes whenever the incinerator burned our collective garbage.

I don’t think this patch of dirt was what my second-grade teacher had in mind when she told our class that each of us was going to grow our own personal garden over Spring vacation. Mrs. Abbey surely expected something more like the neat rows of bright green mounds pictured on the packets of watercress seeds that she distributed to the class. She also handed out long wooden boxes from five-pound bars of Velveeta cheese and mimeo-graphed instruction sheets. We were to fill the box with soil, sprinkle the seeds on top, and water carefully and regularly enough to keep the soil moist. Our care would be rewarded by a thick crop of green plants—just like real farmers!

As soon as I got home, I took a spoon out of the kitchen drawer to do my digging and ran downstairs to the courtyard garden patch. I filled my cheese box with the hard, crumbly, acrid-smelling dirt, leaving little craters along the inside edge of the curbstone. Then I brought it upstairs, sprinkled the package of seeds on top, and held it under the kitchen faucet until the seeds floated on the surface and dirty water trickled out the bottom. My mother, seeing the puddle in the sink, decided the best place to put my “garden” was on the metal fire escape outside the kitchen window.

At first, I checked the box every day, but when nothing seemed to happen, I lost interest and forgot all about it. It wasn’t until weeks later, when we were told to bring our boxes back to school, that I looked out at it again.

What I found seemed like a miracle to me. Not only was the wooden box topped by a fuzzy crop of bright green watercress, but a variety of exotic plants had appeared out of this curly mat and formed a miniature jungle.

Tufts of green grass arched gracefully over the edge of the box; a clump of clover mounded up to fill one whole corner with little globes of yellow flowers; and best of all, along a tangle of jointed stems that spread over the edges of the box and onto the metal slats of the fire escape, a spiderwort brandished an exuberant display of deep purple blossoms.

Together, my mother and I unwound the long spiderwort and carefully placed the box garden into a paper grocery bag for me to carry to school. Every block or so I would stop to peek into the bag so I could make sure I had not imagined it all.

Once my box and I arrived safely, I extricated the garden and placed it on my desk. The other children all had their own versions of our agricultural experiment sitting in front of them. Every one of theirs was covered by a neat blanket of watercress, fuzzy and soft as lambswool. Only mine had blooming clover and sprays of grass and velvety purple flowers that tumbled luxuriously down the sides of my desk.

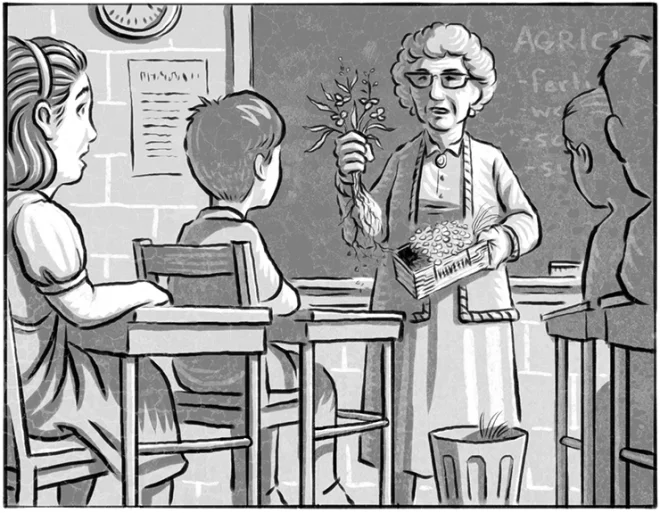

Mrs. Abbey slowly walked up and down between the desks, nodding at each box of watercress approvingly and lining it up with the others on the windowsill. Then she came to me. I tingled with pride when she lifted up my beautiful jungle and carried it to the front of the room.

“Here,” she began, pointing to my burgeoning planter and frowning sternly at me, “here’s what happens when a farmer doesn’t take care of her crops. Seeds that don’t belong start crowding out the ones we want.” She paused, plucking out the tufts of grass and dropping them into the wastebasket next to her desk. “And we certainly cannot allow other plants to take over”—she yanked out the clover—“or we will lose the good crops and have nothing to eat.”

Finally, she wrapped a fist around the spiderwort and pulled it out, roots and all. “This, children, is a weed.” She held it up like a trophy. “A weed is any plant that grows where it doesn’t belong, and a good farmer must get rid of them.” With this she dropped the spiderwort into the wastebasket. She brushed the soil off her hands back into the box and pushed down the dislodged bits of watercress.

Thus purged, my garden box was ready to join the others on the windowsill. I could no longer tell which one was mine. It was very hard for me to understand why it was that the pretty flowers didn’t belong. I remember finally deciding that it must have been so that all the boxes would look exactly alike.

That afternoon when I got home, I told my mother what had happened. She agreed that Mrs. Abbey must have wanted all the gardens at school to look the same. But at home, she assured me, a garden could look any way I wanted. Then she took hold of my little hand and led me outside, out to the round garden patch in the middle of the courtyard. Cascades of purple-flowering spiderworts poked out from the spaces between the privet bushes and extended in all directions, even spilling over the curbstone and onto the dry concrete that surrounded it.

“There,” my mother said, “that’s where they are meant to grow. And aren’t they lovely?”

She gave my hand a gentle squeeze.

“Just like you.” ❖

Previous

Previous