I knew a girl who was so pure.

She couldn’t say the word Manure…

That lady is a gardener now.

And all her views have changed, somehow…

In fact, the garden she has got

Has broadened out her mind a lot.

—Reginald Arkell

When, aged 40, I had my youngest son, I was considered an “older mother” (nowadays I would have to be another decade along to qualify), and the birth was considered somewhat risky. After it was successfully achieved, no first mother could have been more awed or elated. I was left alone in the birthing room before being moved, and an older orderly came in to clean things up for the next mom-to-be (groaning somewhere along the corridor). I confided to her the ecstasy of my feelings as she shuffled around with armfuls of sheets.

“Very nice,” she said. “Pity it has to be so messy.”

Nature is inclined to be messy, but as gardeners and mothers know, those who avoid mess are apt to lose out on ecstasy, as well. If there had to be a test to distinguish addicted gardeners from “occasional users,” it would be easy to contrive: exposure to a giant, odiferous, steaming dung heap. The true gardener would approach it, probably on bended knees, bursting into thankful praise and begging for a container to haul some away immediately. Like Karel Capek (in The Gardener’s Year), he would already smell the perfume of next year’s flowers in “the reeking strawy heap” and imagine spreading it on the garden “as if he were spreading marmalade on his children’s bread.”

In distinguishing between gardeners and non-gardeners, we safely assume that St. Paul was in the latter category, since he “suffered the loss of all things, and do count them but dung.” We know, however, that some of his Biblical contemporaries appreciated manure. Remember the parable of the man who ordered his fig tree cut down because it would not bear and “encumbereth” the ground? His gardener asked for a year’s reprieve to “dig about it and dung it.” We are not given an ending to this tale, but personally I think the dung did the trick. Anyway, if manure is not a direct route to heaven, it has been an integral part of gardening since gardening began. Some scholars think that the earliest husbandry of plants arose when inhabitants of settlements noticed extra-large specimens of wild plants in their midden heaps and got the idea of cultivation.

The Romans used manure, not only “green manure,” which is the turning over of cover crops into the soil, but ordinary stinking animal—and human—waste, as well. Columella, who wrote De re rustica about 60 A.D., tells us “The gardener should…glut the starving earth [with] whatever stuff the privy vomits from its filthy sewer.” When my family and I lived in Italy in the early 1960s, we had what was really a Roman privy—a beautiful marble slab with a hole in it and a large pit beneath. When the pit grew full, the landlady asked the old peasant woman in her employ to empty it for us, which considerably discomforted me, although she and her son accepted the job quite cheerfully. They used an old Nazi helmet on the end of a stick to bale the stuff out (the area had been occupied by Germans during war) and they buried the contents in the roots of an orange tree. I must say the oranges the tree produced were exceptionally luscious.

As populations increased in Europe, the intensive cultivation needed to support them could not have been achieved without the use of manure. Farmers rotated crops, ploughed in legumes, left land fallow—and used any and every kind of manure. Different dungs were considered efficacious for different purposes—there were “hot” and “cold” manures, which were best for hot or cold soils. John Reid in The Scots Gard’ner (1683) tells us that horse dung is hot and sheep dung is cold. In 1725 Leonard Mascall, in A Book of the Arts and Maner howe to plant and graffe all sorts of trees, recommends “the old pisse of old men … they shall bring fruite much better …” Shakespeare does not particularize on the merits of different kinds of manure, but he understood their importance. In Henry V, he talks of:

“Covering discretion with a coat of folly;

As gardeners do with ordure hide those roots

That shall first spring and be most delicate.”

Anyway, as John Parkinson said in 1626, “You must under-stand, that the less rich or more barren your ground is, there needeth the more care, labour and cost to be bestowed thereon.” Speaking of work, the labor of spreading manure is built into its name: the word literally means “to do work by hand.”

Perhaps for that reason, settlers in the New World placed less value on manure. They had a completely different approach to fertility. The Native Americans on the East Coast had shown Europeans how to bury fish in plantings of maize, but the settlers were not skilled in the ways of the New World and often had not been skillful farmers in the Old. The easiest way to cultivate was to take over new land when more fertile ground was needed, and that is what they often did.

The practice was not universal (Dutch and German farmers in particular stuck to the old ways), but it was widespread enough to cause comment. The Swedish traveler Peter Kalm told how “a person had bought a piece of land, which perhaps had never been plowed since Creation…the first time he got an excellent crop. But the same land…without being manured, finally loses its fertility of course. Its possessor then leaves it fallow and proceeds to another part…which he treats in the same manner.”

Thomas Jefferson, writing to George Washington in 1793, said manure was not usually a calculation in the cost of farming “because we can buy an acre of new land cheaper than we can manure an old one.” This especially applied to tobacco farms, where few cattle were kept and the crop greatly depleted the soil, as leafy crops do.

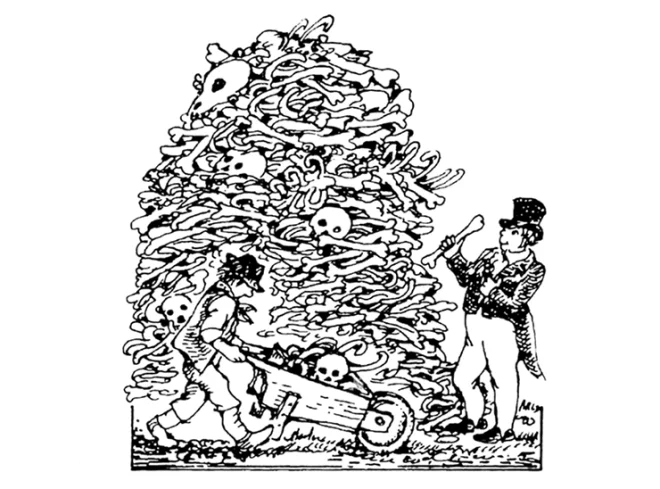

In the 19th century, things changed. There was less available land for the taking, and Americans had begun to realize that the wilderness was finite. A love of nature became fashionable and expanding civilization regarded with growing suspicion. At the same time, there was a new understanding of how plants worked and what their needs were. Manure and the science of manure became a much-discussed topic: different kinds of manure were tried by gardeners both in England and America. In England there was a craze for bone manure, especially after 1829 when Mr. Anderson of Dundee invented a bone-crushing machine, and bones were imported to Britain on a massive scale. Baron Liebig of Munich accused the British of collecting bones from Europe “like a vampire” and said that they had ransacked the battlefields of Leipzig, Crimea, and Waterloo, thereby collecting the “manurial equivalent of three millions and a half men.” In the United States, fish were more popular. Whiting were sold for a dollar a thousand and were “said to affect the soil advantageously for a considerable length of time.” Guano was “discovered” in the middle of the 19th century (although it had always been used in Peru), and the deposits on the Chincha Islands were soon exhausted. The Royal Agricultural Society then offered a huge prize for the “Discovery of a manure equal in fertilizing properties to the Peruvian guano, and of which an unlimited supply can be furnished.” Meanwhile an imaginative entrepreneur started selling “Native Guano,” which was dried city sewage (and probably just as efficacious). All this demand was eventually met by the invention, at the end of the century, of chemical fertilizers.

One of the advantages of chemical fertilizer was that, well, it wasn’t manure. Even at the height of the Victorian garden craze, some people weren’t overly fond of the stuff. John Loudon, writing in the 1830s, wondered why “gentlemen who are so delicate in other matters should make no scruple to eat vegetables and fruits grown among the vilest filth and ordure.” He instructed gardeners to haul manure “early in the morning, that the putrescent vapours and dropping litter may not prove offensive to the master of the garden, should he, or any of his family or friends, visit that scene.”

But chemical fertilizers, as we now know, are not the same as good old manure. Fortunately, almost anything rotten makes good manure, from old wool or grapefruits to your tax collector’s body. People who love compost can drive you crazy, eyeing your eggshell before you’ve finished your egg, hovering over you while you clip your nails. Everyone knows that really ardent gardeners have a different moral code from everyone else.

Even so, it’s rather amazing that such refuse can work such wonders. Walt Whitman, needless to say, puts it more beautifully than I can: “O how can it be,” he asks, “that the ground itself does not sicken?” How is it that we can spread it with filth and be re-warded with the brilliant tenderness of rebirth? No wonder true gardeners kneel before heaps of manure and see not putrefaction, but miracles to come. ❖

Previous

Previous