Either side the clock in my workroom hangs a weapon.

On one side is a fearsome musket that one of my ancestors is said to have captured in the War of the American Revolution. On the stock is crudely punctured the legend, “Samuel Mash, 1777.” The bayonet and its leather sheath are still in place; I shudder to think what horrible traffic that blade may have executed. There is also the bullet-case, made of a block of wood into which two dozen holes are bored for the balls, three-fourths-inch wide and nearly three inches deep, enclosed in a crude leather case with a flap over the top and a pocket on the front. The old flint-lock and the priming-pan are yet in condition and the flint itself is in place. Empty of its contents and lacking the ramrod, this gun weighs eight and one-half pounds. It is four feet eleven inches long from muzzle to butt; it should have sent its bullet straight.

It was a hardy man that wielded this laborious firearm, in frontier days of crude equipment and of long journeys by sinking roads. Not many men could it have despatched, for it must be loaded again by the muzzle after every single discharge; the loose powder was poured in, proper wads were inserted, the great homemade bullet placed, and all rammed home with the rod; the flint was adjusted; the pan was primed; and the weapon was ready for destruction, if it did not get wet or miss fire. But this weapon, and others like it, did their work well and we in the later day enjoy the fruits of their conquest; yet it has not taught us to abolish weapons for human slaughter. I like to think that the old gun hangs on my wall as a silent monitor of yet better days.

The other side the clock hangs my father’s hoe. No other object is so closely wrought into my memories; my father left it hanging in the shed before the summons overtook him to leave the farm forever and I brought it home with me that I might know it every working day.

This is not merely a hoe. It is a symbol of a man’s life. One of my persistent memories is the sound of that hoe in the early morning when the lids of sleep were so slowly slowly opening, and I knew that he was in the garden and all was well. Clish, clish, clish in an even rhythmic easy subdued cadence the hoe moved up and down the rows, never chopping, never hacking, never faltering, for my father was a hoeman as another man might be a welder or a wheelwright, taking pride in the skill of his handiwork. Very smooth and even the ground was left, with a thin loose surface such as in the later sophisticated days we came to know as the earth-mulch. Six-foot-one he stood, and yet he scarcely stooped; with his right hand he grasped the handle near its end and always in the same way, with the thumb lengthwise on the wood, the four fingers clasped underneath, and the end of the stock not projecting from the back of the hand. Four inches from the end a hollow has been worn by the ball of the thumb, and underneath are furrows where the fingers grasped.

When the job was finished the hoe was cleaned and hung in its own place; no one else ever touched it. There was no proscription on it, but we would not think to use his hoe any more than to wear his shoes or his hat.

For how many years he used that hoe I do not know, but my memory does not go back to the time when it was not a part of him. In his later years, he felt that the old hoe was becoming too much worn and the handle too weak, so he hung it away and purchased another. This other hoe, much worn away, is also preserved, but is relatively a modem affair and of a different breed.

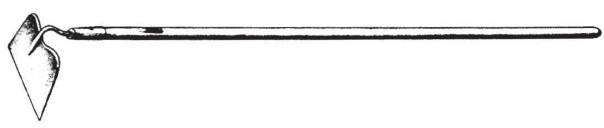

Wonderful execution the old hoe was wrought. It would be difficult to estimate how many millions of young weeds have succumbed to it; the big weeds were pulled by hand, but the little growths fell beneath its steady even march. It was a maxim with us that no weed should go to seed on the farm. And the hoe performed the acme of good and thorough surface tillage; this was its major contribution. The implement shows its service; the blade is worn to a thin plate with evenly rounded ends, three inches wide and six inches long; the handle at the shank is worn down to half its strength, and the furrows are deeply cut by grit and storm and time along the grain of the ashen wood.

It must have been good material in that handle and thimble and blade. He told me that it was one of the first hoes made at the State Prison at Jackson. He came into Michigan from the Green Mountains in 1841. The farm on which I was born was taken from the wilderness about 1855, and long before that he had purchased a farm elsewhere. Recently I applied to the Warden of the Michigan State Prison for information about the beginnings of the hoe-making there. He sent me an interesting report by one of the prisoners, who has been interested in the history of the institution; and from this I learn that contracts for hoe-making there were begun as early as 1848.

My father’s hoe goes back, therefore, to the beginnings of an industry, and it is a witness of all the modern developments in manufacture and in agriculture. It spans one of the significant turning-points in history, when manufacture succeeded handicraft and when farming emerged from a simple separate occupation to a commanding part in the discussions of men.

Yet, even so, a hoe is for personal and not for corporate use. I doubt whether we breed hoemen any more. Now and then I see an old man who can use a hoe with purpose and skill and with a feeling of good workmanship, but for the most part we disdain these simplicities and pride ourselves on grander things. Thereby do we miss some of the essentials and deprive ourselves of many simple means of self-expression. When I see someone using a hoe I do not catch the feeling of pride in the implement or satisfaction in the deft handling of it, quite aside from its gross usefulness in opening the ground and covering the seed.

I remember that I looked forward with pleasure to hoeing the corn, a labor that now arouses surprise. For one thing, it was escape from harder labors; and the long rows of corn invited me, with the burrows of moles and mice, the yellow-birds that nested in trees in the growing summer, and the runnels that heavy rains had cut. The odors of the corn and the ground were wholesome and pleasant. Quickly the growing corn had made a forest since planting time, and when it became head high to a boy and the tassels were in the tops, the field became a hiding-place for many wild creatures and there were mysteries in the shadowed depths; we went straight into these mysteries when we hoed the corn for the last time in the season, and every fence-corner at the end of the rows was another world of interest. Father took one row and I another alongside, and patiently we went back and forth across the field, laying the pigweeds and thistles along the spaces, straightening up the lopped and broken stalks. The rows looked thankful when we had done with them. There was not much conversation; there did not need to be; there was interest all along the route; we were part of the silence of nature; but the few words I heard were full of meaning and they sank deep.

Often I am tempted to contrast these two old implements, the gun and the hoe, and to estimate their values. I reflect that the gun does not express a man’s life, but is a weapon to be used on occasion, and for this one the occasion was indeed dire and heroic. Its conquests ended, it was hung away and was brought out only for display. But the hoe was a companion throughout a man’s productive lifetime. It was never on parade. It did its work steadfastly and well, and no one paused to give it notice. It made no mourners. It helped to make the land better, the crops better, and the man better, and it entered into the life of a boy. If the first requisite of social service is that a man shall do his own work well, then the old hoe has been verily an implement of human welfare and there need be no apology for hanging it alongside the heirloom firelock.

Now that we are so eagerly aware of all our troubles, the hoe recalls another time; and as I look back on those cornfield days I am aware that I never heard a complaint about farming from my father. We did not think of it that way. We were farmers; it was ours to make the farm worth while and to be satisfied. We did not compare our lot with that of others. We went about our farming as the days came, the program being determined by the weather and the seasons. Nor do I recall laments about the weather: it will come out right in the end, we shall follow the Lord’s will,—this was the attitude.

Perhaps these practices and outlooks cannot develop the most skillful or productive farming, but farming was not then a competitive business. There were years of “glut,” but we had not heard about “surplus.” We needed little and were never in want. We had not learned to substitute machines for men. We knew nothing about “efficiency,” and cost-accounting was not even in the penumbra of dreams. The men of that stripe and generation would have resented the idea that farming can be measured by money; it was too good for that.

All this is very crude and far away; but the old hoe still hangs by the clock as the days are ticked off one by one, and I am glad that it led me through the rows of corn. ❖

Previous

Previous