Read by Matilda Longbottom

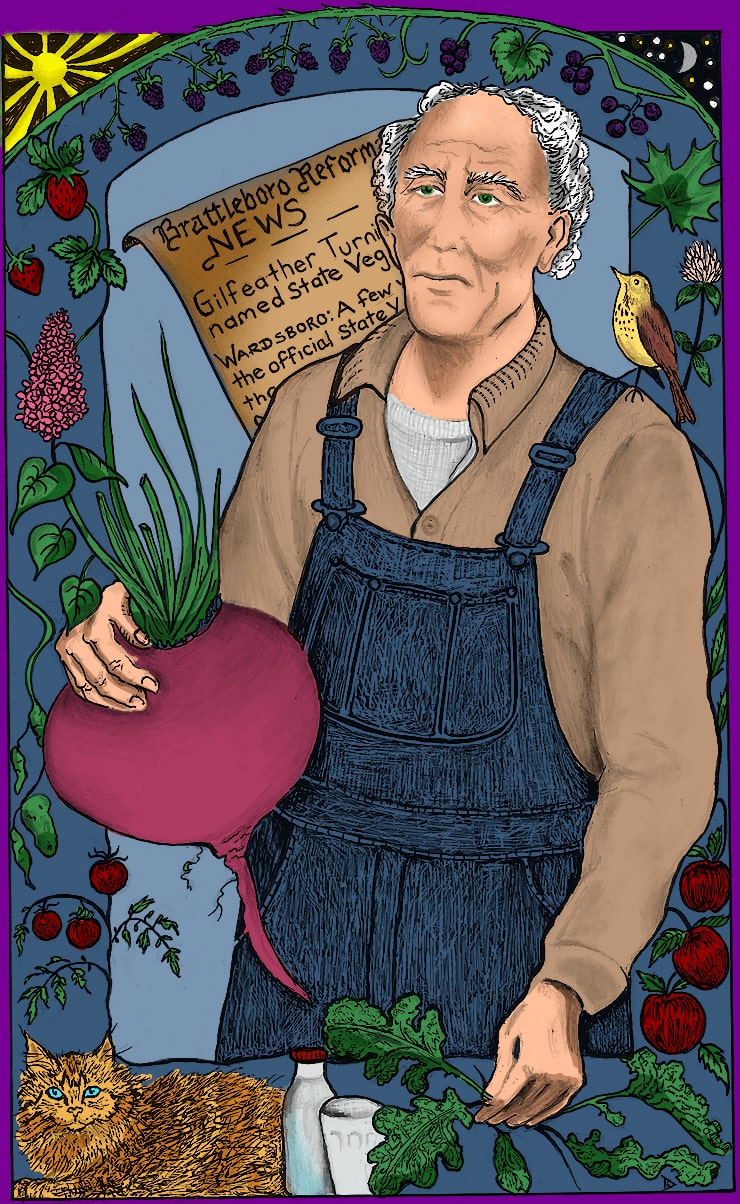

As of July 2016, Vermont has an Official State Vegetable. It’s the Gilfeather turnip, a solid and stodgy veggie that—given a little encouragement—can grow to the size of a groundhog. The turnip, said by its fans to be remarkably mild-tasting and delicious, was either painstakingly developed or serendipitously stumbled upon by John Gilfeather of Wardsboro, Vermont, a tiny town in southern Vermont’s Green Mountains. It’s noted for—other than turnips—nothing much.

Gilfeather, described as “a lanky bachelor of few words,” bred, invented, and/or found his turnip sometime in the late 1800s. He seems to have been possessive of it to the point of paranoia, snipping off leaves and roots before sending his crop to market, and hoarding seeds, so that nobody else could possibly manage to propagate it. He eventually slipped up, which is why people are still growing them, and why Wardsboro today is the site of an annual turnip festival, touted (probably truthfully; there can’t be that much competition) as America’s best turnip culinary event.

The festival, held in October, features an outdoor market; musicians; a turnip cart selling fresh turnips; an all-turnip community meal featuring turnip casseroles, turnip soups, turnip bread, turnip salad, and mashed turnips; and a turnip contest with prizes for the largest and the ugliest turnip.

There is even a commemorative turnip song, courtesy of Wardsboro native Jim Knapp, that runs:

Well, back in eighteen-hundred whatever

A man came along by the name of

Gilfeather. He brought along some turnip seeds

And put them in the ground

And that’s how the Gilfeather turnip

Came to our tiny town.

There’s more, but you get the idea. Possibly never has a turnip received so much adulation.

Vermont turns out to be not only the 14th state to join the Union but also the 14th state to appoint an Official Vegetable. The custom of adopting such state symbols dates to the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, a spectacular six-month extravaganza popularly known as the Chicago World’s Fair. During it, some 27 million visitors toured 65,000 exhibits, among them a U.S. map made of pickles, Bach’s clavichord, a herd of ostriches, a 22,000-pound Canadian cheese, and a 1,500-pound copy of the Venus de Milo in chocolate. Also featured at the Fair was a National Garland of Flowers, for which each state was asked to select a representative official flower.

Minnesotans, an agreeable bunch, promptly picked the lady slipper. For most states, however, state flower choice was not so simple: New Hampshire, for example, torn between the apple blossom and the purple lilac, ended up with a pair of botany professors arguing the relative benefits of each before the state legislature. (Purple lilac won.) Other states, beset by irreconcilable differences, opted for compromise, adopting both a state flower and a state wildflower, or threw up their hands and turned the vote over to state schoolchildren. Most states hadn’t managed to decide on a state flower by the opening of the World’s Fair.

Despite the attendant conflicts, state flowers proved to be so popular that they were soon followed by a host of other official state symbols, among them birds, trees, animals, insects, reptiles, fossils, minerals, gemstones, songs, and folk dances. Vermont now has an Official State Beverage (milk), Maine has an Official State Cat (Maine coon), and Texas has Official State Footwear (the cowboy boot).

Like the beleaguered flowers, however, state fruits and vegetables have often proved more controversial. While six states chose the apple as their state fruit, three the strawberry, and two, the peach, Alabama—unable to make up its mind—picked the blackberry as state fruit and the peach as state tree fruit. North Carolina’s state fruit is the scuppernong grape, but it also voted in two official state berries (strawberry and blueberry). Tennessee and Ohio, conforming to a strictly botanical definition of fruit, adopted the tomato as state fruit. Arkansas, sitting on the fence, decreed the tomato to be both the state’s official fruit and official vegetable. Louisiana made the sweet potato its state vegetable, but gave a nod to the tomato, naming it the Official State Vegetable Plant.

Clearly this isn’t easy.

Vermont’s Gilfeather turnip weathered a long battle with kale, also a state favorite, before its Official Vegetable status was finally signed into law. The final decision, helped along with lobbying by several classes of Wardsboro elementary students, seems to have been affected by the fact that the turnip, unlike kale, is a Vermont native. Which the Gilfeather is, sort of. On the other hand, it’s not exactly a turnip.

Scientifically speaking, the Gilfeather turnip is a rutabaga—the result of a cross between turnip and cabbage that took place, botanists guess, at some point in the Middle Ages, possibly in Scandinavia. Rutabaga itself is an old Swedish word, a combination of rot (root) and bagge (something short and stumpy), which pretty much sums up both rutabaga and turnip.

What we actually eat, when consuming both or either, is part root, part starch-stuffed lower stem. They taste best yanked up late in the season, since turnips and rutabagas—like carrots, parsnips, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts—sweeten up in cold weather. Chilly temperatures nudge the plants into converting starch into sugar, which acts as a form of natural antifreeze. And if there’s anything we’ve got here in Vermont, it’s chilly temperatures.

So next year in the garden, we’re growing Gilfeather turnips. After all, we’ve got the weather for it. And as the possessor of a brand-new state vegetable, I figure it’s the least we can do. ❖

Previous

Previous